Paul Revere's Ride (12 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Once again, Paul Revere got wind of the impending expedition before it sailed. The information came to him in a roundabout way, perhaps from the Colony’s secretary, Thomas Flucker, who worked in Province House with General Gage. Flucker may have passed on the news to his Whig son-in-law, bookseller Henry Knox, who relayed it to Paul Revere.

41

Revere appears to have been informed only that something was stirring in the harbor. His mechanics’ network went instantly into operation. The day before the expedition was to depart, three

men rowed out to Castle Island to find out “what was acting,” to use Revere’s favorite phrase. As they approached the island, the British soldiers were waiting, and the Boston men were arrested for trespass. One wonders if the report from Gage’s headquarters may have been leaked to Revere deliberately, as bait for a trap. In any case, the mechanics were caught, and held on the island from Saturday afternoon until Monday morning, “lest we should send an express to our brethren at Marblehead and Salem.”

42

Had General Gage been less Whiggish in his respect for the rule of law, Paul Revere might have worn these handcuffs and leg irons, which were later recovered from the wreck of HMS

Somerset

on Cape Cod and are at the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum.

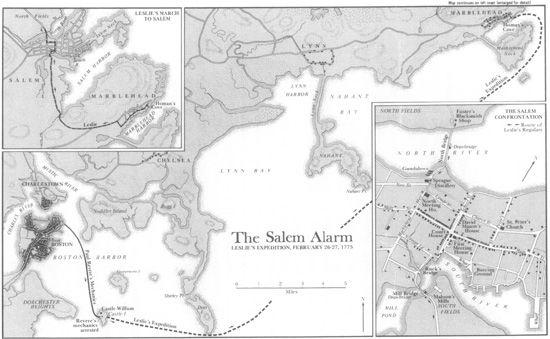

While Paul Revere’s mechanics were kept prisoner, the British troops of the 64th Foot got off without detection, 240 strong. A little after midnight, February 26, 1775, their transport sailed north across Massachusetts Bay on a course for Marblehead. They reached their destination about nine o’clock in the morning of February 27, and dropped anchor by a secluded beach in Homan’s Cove on Marblehead Neck. Colonel Leslie kept his soldiers hidden in the hold. Only a few crewmen were visible on deck.

43

It was a quiet Sunday in Marblehead, and the countryside was silent and peaceful. The Regulars waited patiently until the people of Marblehead went to their meetinghouses for their afternoon sermon. Then, between two and three o’clock in the afternoon, Leslie ordered his men into action. His Regulars swarmed out of the ship’s hold, landed ashore, and quickly formed on a road near the beach.

44

Colonel Leslie gave the order to advance, and the long red

column went swinging into its march toward Salem, five miles away. The Regulars were confident that nothing could stand in their way, and decided to announce their presence. The fifes and drums of the 64th Foot suddenly shattered the stillness of the Sabbath with a raucous rendition of Yankee Doodle.

The landing of the soldiers had already been observed by several men of Marblehead, who sprinted to their meetinghouse and sounded the alarm. Whig leader Major John Pedrick decided to warn Salem, but he could get there only by the road the Regulars had taken. Major Pedrick mounted his horse, and rode slowly past the Regulars, politely saluting Colonel Leslie, whom he had met before. Leslie returned the salute, and ordered his regiment to “file to the right and left and give Major Pedrick the pass.”

When out of sight Pedrick put spurs to his horse, and galloped on to Salem. He went to the home of Colonel David Mason, who ran into the meetinghouse, where the congregation had gathered for the afternoon service, and shouted as he came down the aisle, “The Regulars are coming after the guns and are now near Mal-loon’s Mills!”

Bells began to ring and drums beat “to arms” throughout the town. The people poured out of their churches and ran to save the guns. Baptists and Congregationalists forgot their differences and joined in a common effort. Even Quaker David Boyce hitched up his team and helped to haul away the heavy cannon. Some weapons were taken to an oak woodlot and hidden under the leaves. Others were carried to a remote part of town called Orne’s Point.

45

Meanwhile, the British troops were on the march. To delay them a party of townsmen hurried to a bridge between Salem and Marblehead and frantically ripped up some of the planking to delay the Regulars. Colonel Leslie’s column was forced to halt while a party of soldiers repaired the structure. The Salem men won a few precious moments for the teams who were removing the cannon. But the Regulars soon improvised a surface over the bridge and crossed into Salem center, where they halted for a moment in Town House Square.

The townspeople watched as several of their Tory neighbors came forward. One was seen “whispering in the Colonel’s ear.” Then the British column started off at a quick-march, straight toward the cannon, with a large crowd of Salem men and boys walking beside them.

In their path was a drawbridge over an arm of the sea called North River. Just as the soldiers approached it, the men of Salem raised the drawbridge from the north side. There was no other way across. The troops were forced to halt at the bridge.

Colonel Leslie hurried forward, and demanded to know why the men of Salem dared to obstruct the King’s highway. They replied that the road belonged to them. The British commander “stamped and swore and ordered the bridge to be lowered at once,” threatening to open fire if he was not obeyed. Militia captain John Felt warned him, “You had better be damned than fire! You have no right to fire without further orders! If you fire you’ll all be dead men.”

The crowd began to grow. Several Salem men sat provocatively on the raised edge of the open drawbridge, dangling their feet and shouting defiantly at the Regulars, “Soldiers! Red Jackets! Lobster Coats! Cowards! Damnation to Your Government!”

While the Salem men gathered at the head of the British column, the Marblehead Regiment was mustering behind its rear. These Marblehead men were a special breed. Many were cod fishermen—rugged, weatherbeaten, hard-handed seamen who earned their living in open boats on the dangerous waters of the North Atlantic. Some were veterans of the French wars. They were as stubborn and independent as their Boston cousins, and feared no mortal power on this earth—least of all the red-coated Regulars who had invaded their town. The men of Marblehead moved into strong positions along the Salem Road, and prepared to fight.

46

It was a sharp wintry New England day. As the Regulars stood waiting in their ranks, some began to shiver in the damp cold. The men of Salem taunted them. One shouted across the river, “I should think you were all fiddlers, you shake so!”

47

In the river near the bridge were three large sailing scows called “gundalows” in the old New England dialect. Colonel Leslie noticed the boats and ordered his troops to seize them. The Salem men moved more quickly. They jumped into the boats and smashed their bottoms to keep the Regulars from using them. The soldiers ran to stop them, threatening to use their bayonets. A Salem man named Joseph Whicher, the foreman of a distillery, rose up before them and defiantly tore open his shirt, daring the troops to attack. An infuriated British soldier lunged forward and “pricked” the American’s naked chest with his bayonet.

48

The mood of the crowd began to change. They closed in around the soldiers, who pushed them back with bayonets. Suddenly, a man dressed in black moved through the throng toward

Colonel Leslie, and spoke to him in a voice that demanded to be heard:

“I desire you do not fire on these innocent people.”

“Who are you?” said Colonel Leslie.

“I am Thomas Barnard, a minister of the gospel, and my mission is peace,” the clergyman replied. The two men, one in black and the other in red, began to talk. The hour was growing late—five o’clock in the evening. The winter sun was going down, and wind was cruel in the damp salt air.

Colonel Leslie had reason to be concerned, not merely for the success of his mission, but the safety of his force. Whig leader Benjamin Daland (today remembered as the Paul Revere of Salem) had galloped to Danvers with the news of the Regulars. Now he was back again, and many others with him. By five o’clock militia were streaming into Salem from as far as Amesbury, twenty-five miles to the north.

As more men poured into the town, the Salem minister proposed to the British colonel a cunning Yankee compromise—the bridge would be lowered if the Regulars promised on their honor to march only to the forge about 100 yards beyond. If they found no cannon they were to turn around and go back to their ships. Colonel Leslie was willing to accept those terms, knowing that he could accomplish nothing more at that late hour. The people of Salem were happy to agree, knowing that the cannon were safely removed.

The drawbridge came creaking down. The British soldiers marched solemnly across it, found nothing, and turned to march back again. As they started their retreat, a window flew open in a house by the road, and a young Salem woman named Sarah Tarrant thrust out her head. “Go home,” she screamed at the Regulars, “and tell your master he sent you on a fool’s errand, and has broken the peace of our Sabbath.” She added contemptuously, “Do you think we were born in the woods, to be frightened by owls?” An frustrated Regular raised his firelock and took aim at her head. Sarah Tarrant said defiantly, “Fire, if you have the courage, but I doubt it.”

49

The British troops returned ignominiously to their ship, fifes and drums playing with empty bravado. They were escorted by a vast crowd of men from Salem and Danvers and many other towns. As the column crossed into Marblehead, and the men of that community also came out of their positions and joined the procession, marching in mock-cadence beside the British troops.

As the Regulars boarded their transport and sailed away, American militiamen converged on Salem from many towns in Essex County—from Danvers and Marblehead, Beverly and Lynn End, Reading and Stoneham. When they learned that the Regulars had left empty-handed, many shared a sense of triumph that made the Imperial cause seem not evil but absurd. An American journalist commented, “It is regretted that an officer of Colonel Leslie’s worth should be obliged, in obedience to his orders, to come upon so pitiful an errand.” Even Loyalists were appalled by what had happened. Thomas Hutchinson wrote, “It is very uncertain whether he succeeded in the errand he went upon.”

50

General Gage confessed in his candid way that the mission had been a “mistake.” Worse than merely a defeat, it was received by both sides as a disgrace to British arms. Something was happening in these alarms that meant more trouble for the Imperial cause than the loss of a few cannon. When Joseph Whicher exposed his naked breast to a British bayonet, and Sarah Tarrant dared a Regular to fire “if you have the courage,” a new spirit was rising in Massachusetts. Each side tested the other’s resolve in these encounters. One side repeatedly failed that test.

51

Why it did so is a question of much importance in our story. Had General Gage been the tyrant that many New England Whigs believed him to be, the outcome might have been very different. But Thomas Gage was an English gentleman who believed in decency, moderation, liberty, and the rule of law. Here again was the agony of an old English Whig: he could not crush American resistance to British government without betraying the values which he believed that government to represent.

On the other side, Paul Revere and the Whigs of New England faced no such dilemma. Their values were consistent with their interests and their acts. That inner harmony became their outward strength.

Inevitability as an Act of Choice

Inevitability as an Act of Choice