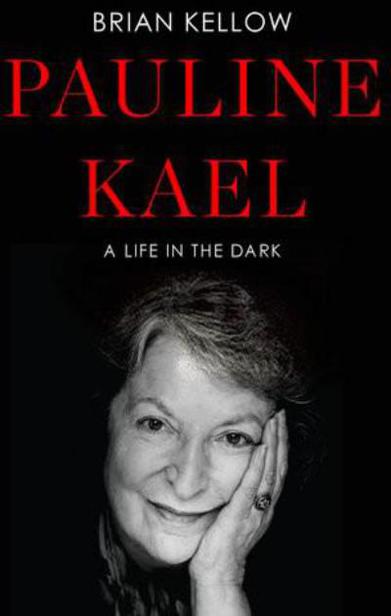

Pauline Kael

Authors: Brian Kellow

Table of Contents

ALSO BY BRIAN KELLOW:

Ethel Merman: A Life

The Bennetts: An Acting Family

Can’t Help Singing: The Life of Eileen Farrell

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2011 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

All rights reserved

Page 419 constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Kellow, Brian.

Pauline Kael : a life in the dark/ Brian Kellow.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Kellow, Brian.

Pauline Kael : a life in the dark/ Brian Kellow.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN : 978-1-101-54532-4

1. Kael, Pauline. 2. Film critics—United States—Biography. I. Title.

PN1998.3.K34K46 2011

791.43092—dc23

[B] 2011021798

PN1998.3.K34K46 2011

791.43092—dc23

[B] 2011021798

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

To my father, Jack Kellow, who loves shoot-’em-ups

To my mother, Marjorie Kellow, who loved

The Godfather

and

Prizzi’s Honor

, and thought ’40s women’s pictures were “crap”

The Godfather

and

Prizzi’s Honor

, and thought ’40s women’s pictures were “crap”

And most of all to my brother, Barry Kellow, whose movie love turned out to be contagious

INTRODUCTION

I

n the beginning, even the French had their doubts about Louis Malle’s

Murmur of the Heart

. The director’s 1972 film was a memory piece that drew on elements of his own childhood. In it, a timid fifteen-year-old boy grows increasingly distant from his bourgeois French father and increasingly attached to his freewheeling Italian mother. After a bout with scarlet fever reveals that the boy has a heart murmur, his mother takes him to a health spa, where, free from the constraints of their ordinary lives, mother and son are drawn closer than ever—so close, in fact, that one night, on the heels of a boozy Bastille Day celebration, they wind up in bed together, quite gently and quite naturally making love to each other.

n the beginning, even the French had their doubts about Louis Malle’s

Murmur of the Heart

. The director’s 1972 film was a memory piece that drew on elements of his own childhood. In it, a timid fifteen-year-old boy grows increasingly distant from his bourgeois French father and increasingly attached to his freewheeling Italian mother. After a bout with scarlet fever reveals that the boy has a heart murmur, his mother takes him to a health spa, where, free from the constraints of their ordinary lives, mother and son are drawn closer than ever—so close, in fact, that one night, on the heels of a boozy Bastille Day celebration, they wind up in bed together, quite gently and quite naturally making love to each other.

When Malle turned in his script for

Murmur of the Heart

, the Centre National du Cinéma refused to come across with any support at all. The script, they complained, depicted “too many erotic sequences . . . in which all manner of perversions are evoked with a disturbing complacency.” Malle was stunned by the reaction. “I certainly did not set out to do a film about incest,” he later recalled. “But I began exploring a very intense relationship between a mother and her son, and I ended up pushing it all the way.”

Murmur of the Heart

, the Centre National du Cinéma refused to come across with any support at all. The script, they complained, depicted “too many erotic sequences . . . in which all manner of perversions are evoked with a disturbing complacency.” Malle was stunned by the reaction. “I certainly did not set out to do a film about incest,” he later recalled. “But I began exploring a very intense relationship between a mother and her son, and I ended up pushing it all the way.”

Murmur of the Heart

went on to enjoy an immense worldwide critical and financial success, and one of its most celebrated admirers was Pauline Kael, who for years had been upending conventional, academically correct notions of film criticism, first as a freelance contributor to a string of film journals and, since 1968, from a truly enviable and distinguished platform as one of two regular authors of the column “The Current Cinema” in

The New Yorker

magazine. To Kael

Murmur of the Heart

was one of the most refreshingly complex and honest views of family life she had ever experienced. Malle was to be commended for seeing “not only the prudent, punctilious surface” of the bourgeois experience “but the volatile and slovenly life underneath.” She noted that advance word on the picture centered on its shock value, because of the element of incest. But for Kael, “the only shock is the joke that, for all the repressions the bourgeois practice and the conventions they pretend to believe in, they are such amoral, instinct-satisfying creatures that incest doesn’t mean any more to them than to healthy animals. The shock is that in this context incest

isn’t

serious—and that, I guess, may really upset some people, so they won’t be able to laugh.”

went on to enjoy an immense worldwide critical and financial success, and one of its most celebrated admirers was Pauline Kael, who for years had been upending conventional, academically correct notions of film criticism, first as a freelance contributor to a string of film journals and, since 1968, from a truly enviable and distinguished platform as one of two regular authors of the column “The Current Cinema” in

The New Yorker

magazine. To Kael

Murmur of the Heart

was one of the most refreshingly complex and honest views of family life she had ever experienced. Malle was to be commended for seeing “not only the prudent, punctilious surface” of the bourgeois experience “but the volatile and slovenly life underneath.” She noted that advance word on the picture centered on its shock value, because of the element of incest. But for Kael, “the only shock is the joke that, for all the repressions the bourgeois practice and the conventions they pretend to believe in, they are such amoral, instinct-satisfying creatures that incest doesn’t mean any more to them than to healthy animals. The shock is that in this context incest

isn’t

serious—and that, I guess, may really upset some people, so they won’t be able to laugh.”

In 1976 she found herself addressing an overflow audience at Mitchell Playhouse in Corvallis, Oregon, home of Oregon State University. For years Kael had been keeping up a hectic schedule of appearances around the country, drawing huge crowds as her fame grew and more and more readers were hanging on her opinions of the latest movies. Although she had little patience for many of the questions that she was asked at these lecture tours, she relished the opportunity to come together with movie-lovers—young ones, especially—during this fertile period of filmmaking that had sprung up in the late 1960s and was still flourishing.

At Mitchell Playhouse she was introduced by Jim Lynch, an associate professor of English at Oregon State, who delighted her by introducing her as “the Muhammad Ali of film critics.” She proceeded to give a stimulating talk on the current state of movies, then took questions from the audience.

“How many times do you see a movie before you write about it?”

“Only once,” replied Kael.

“What about

Persona

?” asked one senior member of Oregon State University’s English faculty. “I had to see it three times before I felt I had any real grasp of it at all.”

Persona

?” asked one senior member of Oregon State University’s English faculty. “I had to see it three times before I felt I had any real grasp of it at all.”

“Well,” said Kael, “that’s the difference between us, isn’t it?” The line played less insultingly than it might read, and she laughed as she said it. Then she went on to explain that she felt the need to write in the flush of her initial, immediate response to a movie. If she waited too long, and pondered the film over repeated viewings, she felt that she might be in danger of coming up with something that wouldn’t be her truest response.

Someone else in the audience persisted with a question along similar lines: “But if you were going to see one movie again, which one would it be?”

“I’d always rather see something new.”

After a few minutes of back and forth, a man in the audience raised his hand and asked about

Murmur of the Heart

, which Kael had reviewed for the October 23, 1971,

The New Yorker

. He told her that, having seen the film again recently, he had found it sentimental and unconvincing, and wondered if she still recalled it with enthusiasm.

Murmur of the Heart

, which Kael had reviewed for the October 23, 1971,

The New Yorker

. He told her that, having seen the film again recently, he had found it sentimental and unconvincing, and wondered if she still recalled it with enthusiasm.

“Yes,” said Kael, “I do.”

“Really?”

pressed the questioner.

pressed the questioner.

After a stiff silence punctuated only by the clearing of throats and the rustling of programs, Kael fixed her gaze on the man for a moment and gave him a catnip smile.

“Listen,” she finally asked. “Do you remember your first fuck?”

“Sure,” he answered, flushing, struggling to hang on to his composure. “Of course I do.”

“Well, honey,” said Kael, after another perfectly weighed silence, “just wait thirty years.”

This was the Kael that her army of readers at

The New Yorker

had come to worship—bold, clear-eyed, pithy, a brilliant critical thinker unafraid of a flash of showmanship.

Do you remember your first fuck?

was, as well as a laugh line, a perfect description of the effect that Pauline always wanted the movies to have on her. She had made similar pronouncements on many occasions. She had discovered her passion for the screen early on, as a child growing up in the farming community of Petaluma, California. It was a passion that grew during her adolescence; through her time as a student at Berkeley; her hardscrabble years when she struggled at a demoralizing series of dead-end jobs to support herself and her only child, Gina; her protracted apprenticeship as a critic for obscure film magazines; up to her emergence, when she was nearing fifty, as the most famous, distinctive, and influential movie critic

The New Yorker

ever had. And her love of the movies reached its apex from the late 1960s through the mid-1970s, a period she regarded as equivalent to some of the great literary epochs in history. Her involvement with her subject matter was anything but casual; it was as tumultuous and irrational and possessive as the most volatile love affair. “Definitely her engagement was libidinal,” observed her friend the film critic Hal Hinson. “She took notes constantly at screenings, that nubby little pencil going constantly throughout the movie. That engagement was as erotic as any erotic engagement could be.... Pauline’s presence was essential, and you felt what she felt: that she was at the center of the culture, and that movies were at the center of the culture.”

The New Yorker

had come to worship—bold, clear-eyed, pithy, a brilliant critical thinker unafraid of a flash of showmanship.

Do you remember your first fuck?

was, as well as a laugh line, a perfect description of the effect that Pauline always wanted the movies to have on her. She had made similar pronouncements on many occasions. She had discovered her passion for the screen early on, as a child growing up in the farming community of Petaluma, California. It was a passion that grew during her adolescence; through her time as a student at Berkeley; her hardscrabble years when she struggled at a demoralizing series of dead-end jobs to support herself and her only child, Gina; her protracted apprenticeship as a critic for obscure film magazines; up to her emergence, when she was nearing fifty, as the most famous, distinctive, and influential movie critic

The New Yorker

ever had. And her love of the movies reached its apex from the late 1960s through the mid-1970s, a period she regarded as equivalent to some of the great literary epochs in history. Her involvement with her subject matter was anything but casual; it was as tumultuous and irrational and possessive as the most volatile love affair. “Definitely her engagement was libidinal,” observed her friend the film critic Hal Hinson. “She took notes constantly at screenings, that nubby little pencil going constantly throughout the movie. That engagement was as erotic as any erotic engagement could be.... Pauline’s presence was essential, and you felt what she felt: that she was at the center of the culture, and that movies were at the center of the culture.”

Other books

Life Beyond Measure by Sidney Poitier

Uncomplicated: A Vegas Girl's Tale by Dawn Robertson, Jo-Anna Walker

Bunch of Amateurs by Jack Hitt

Fairy Tales for Young Readers by E. Nesbit

Tempted in the Tropics by Tracy March

Can't Get Enough of You by Bette Ford

Too Wicked to Marry by Susan Sizemore

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

Bone Hunter by Sarah Andrews