Peace Work (7 page)

Authors: Spike Milligan

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Humor & Entertainment, #Humor, #Memoirs

∗

That night, during the interval, Lieutenant Priest comes round with the wages or, as Hall called it, the Dibs. We sign the Dibs receipt. Hall puts his money in the rosin compartment of his violin case. I think Mulgrew put his on a chain in a money belt in his jockstrap.

After the show, I had planned for Toni and me to go out to dinner. First, a trip in a gondola on a clear starry night. The gondola man can see we are lovers, so he sings ‘Lae That Piss Tub Dawn Bab’*…

≡ ‘Lay That Pistol Down, Babe’.

It is midnight. Toni and I are at a corner table in the Restaurant Veneziana (alas, now defunct – possibly now the Plastic Pizzeria). It’s all candles and Victoriana and dusty enough without being dirty. There are chandeliers with the odd tear-drop missing and white-aproned waiters lubricated by the growing tourism are grovelling and bowing at the going rate. A guitar and mandolin are trilling through Paolo Tosti and Puccini. I send a hundred lire with a request: “Don’t play ‘Lae That Piss Tub Dawn Bab’.”

Toni and I are talking pre-dinner nothings. We watch the dancing calligraphy of the ruby in the wine on the tablecloth, we can hear the waters lap as gondolas pass the window. Please, God, let me die now! I am seeing Toni over a bowl of nodding roses, fallen petals tell of their demise, the sickly sweet smell courts the air. The waiter has held back to allow us our billing and cooing. He now advances with the menus as a shield. He recommends moules marinieres: “

Fresche sta matlina, signorina

,” he tells Toni. Toni orders

vitello

(veal). Today, I’d have told her it was cruel; then, I was ignorant.

“This is very old restaurant, original home of Contessa de Rocabaldi. She die in 1900, some say she poisoned.” Oh? Did she eat here? “Oh Terry, why you always talk crazy?” says my love. “Here stay Greta Garbo.” Oh? I topped up our glasses only to have the bottle taken by the

sommelier

, smilingly outraged at the predation on his domain. He tells us that Valpolicella was the wine of Suetonius. I asked him did he come here? But the joke misfires and he says, no, you see Suetonius died two thousand years ago.

We were alone and eating. I looked across the roses at her and I said what I hadn’t said to a girl since 1939. “I think I love you.” She stopped eating, a

moule

in one hand. (There are no two-handed

moules

.)

She smiled. “You

think

you love me?” I nodded. She raised her glass, I touched it with mine, they lingered together a moment. Then she said, “When you are sure, you tell me again.” And she elevated the glass, then sipped, her eyes on me as she drank. She called the waiter and rattled off something in Italian. He hurried to the duo which then played the ‘Valzer di Candele’, the version from the film

Waterloo Bridge

(with Robert Taylor and Vivien Leigh). She hummed the tune, a few rose petals fell. God, this was different from Reg’s Café in Brockley! I reached out and held her hand and discovered how hard it was eating spaghetti one-handed. But what a romantic night!

It was past midnight when the waiter brought the bill, and two minutes past when I realized I’d left my money in the dressing-room at the theatre. I explain the circumstances, he calls the manager; I explain the circumstances, he calls the police; I explain the circumstances. It ends with me leaving my silver cigarette case and my watch. They were all returned the next night when I paid the bill, the manager now all effusive with smiles. The cigarette case was empty, the bastard had smoked the lot. Like my father said, “Life is six to four against.”

THE CARNIVAL OF VENICE

Y

es, tonight Venice is to have a carnival, the first one since 1939. Before the show, Toni and I sit at an outdoor café in the Piazza San Marco. The pigeons are wheeling in the sunset, and the light falls on the Ducal Palace and the Basilica, two different stories in stone. Around the square, beautiful buildings run cheek by jowl: soaring up is the great Bell Tower, whose doleful bells are ringing out the hour of six, sending more pigeons wheeling from their roosts. People stroll leisurely. One looks at St Mark’s and is lost in wonder, its Byzantine-Gothic shapes catching the light to give a hologram effect. Alas, the four colossal bronze horses that had once graced some Roman quadriga were missing – still in store from the war.

Johnny Mulgrew joins us. “Hello,” he says in stark Glaswegian tones. “So you’re going to buy me a drink?” He tells us Hall is missing again. Are we going to stay on for the carnival? Yes. I order a couple of Cognacs. May as well start the festivities.

“Here, wee Jock, drink this. It’s awfur gude,” I said in mock-Scottish tones. Silently, Mulgrew holds it up then downs it in one, licks his lips, looks at us and grins. It doesn’t take much to make a Scotsman happy.

∗

The show over, we all make for the barge which has been stocked with drinks and food for the night. Our bargee has put little coloured bulbs in our awnings. There were ‘ooos and ahhhs’ as fireworks sprinkled the night sky. All the ferries and gondolas had coloured lanterns. In the Piazza San Marco, there was a municipal band and all the people in fancy dress, some quite fantastic with masks. Some waved handheld fizzers writing graffiti in the air. Gondoliers were outsinging each other, people waved and shouted from passing boats, rockets soar from the Isola di San Giorgio and it’s a starry night!

We open the Asti Spumante and nibble fresh-cut sandwiches. It starts off quite civilized, but gradually the drunks start to manifest themselves. A gondola passes and tosses firecrackers into our boat. Screams and yells from us as they explode like miniature machine guns.

“We should have brought some grenades,” says Bornheim.

“You have anything like this in England?” says Toni to Bill Hall.

“Oh yes, Blackpool,” he says.

We had to stave off several British soldiers trying to board us from gondolas. “Hey, you want Jig-a-Jig?” seems to be their contribution to the gaiety.

The trio plays for dancing. Swing, swing, swing, hot jazz, yeah Daddy! So I can dance with Toni, Bornheim relieves me on the accordion. I had never been relieved by an accordion before. Toni and I try to dance. It’s a crush, but what the hell. It’s nice just holding her. But now the drunks take over. Sergeant Chalky White thinks we need ‘livening up’: he is balancing a glass of beer on his forehead (Where had I seen this all before?) and doing a Russian dance. Why, oh, why, is it always the most untalented that think they are entertaining? “Eyeties can’t fucking sing,” he says and makes us all sing ‘Knees Up Mother Brown’. A barge full of people in Venice and it’s ‘Knees Up Mother Brown’. Then ‘My Old Man Said Follow the Van’. Splash. Riccy Trowler has fallen in the water. We haul him out, he’s giggling.

“He needs a towel.”

“No, I don’t. I need a brandy.”

Toni and I sit it all out at the back of the barge. By 3.00 a.m., Life as we know it on this planet is over. The barge draws to the landing stage and they all stagger on to the Charabong. Chalky White is still manic with energy. “Knocked ‘em in the Old Kent Road,” he sings. Why God? At the Leone Bianco I say goodnight to Toni. Soon I’m in bed. Safe at last! No, with stifled laughter some low-life bastard is trying to fart through the keyhole. Yes, dear reader, FART THROUGH THE KEYHOLE.

I have a hangover. Someone has put a Lipton’s tea chest in my head and the corners are expanding. I get up, someone is revolving the Lipton’s tea chest. I look in the mirror, I am suffering a severe attack of face. My red eyes resemble sunset in Arabia; my tongue is a Van Gogh yellow, I have to push it back in by hand.

Bornheim enters. “Someone’s made a cock-up.”

“Then dismantle it. Here comes the Mother Superior,” I say.

The hotel in Trieste is full, so we are to move to Mestre just up the road. Someone is chopping up the Lipton’s tea chest.

“What’s up?” says Bornheim.

“My head.”

“Yes, I

know

it’s your head.”

“What time is the Charabong leaving?”

“Chinese Dentist.”

“What?”

“Chinese Dentist,* tooth hurtee!”

≡ Two-thirty.

“Please leave.”

I take two aspirins and a bath, feel a little better. I pack my suitcase with a man chopping up the Lipton’s tea chest. It’s nearly Chinese Dentist as I lug my case to the lift. Mulgrew is in it. “First floor,” he says. “Ladies underwear and drunks.”

MESTRE

MESTRE

I

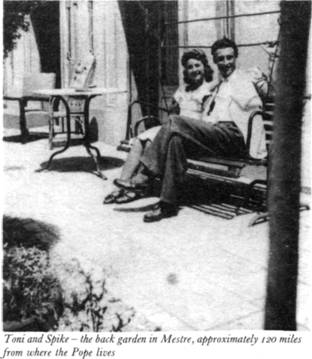

t’s a short fifteen minutes hop to Mestre and the Albergo Savoia, a large one-time country home. It’s rectangular, very roomy with floral curtains and matching furniture. Along the back of the house are french windows which open on to what once was a garden, but is now concreted over. After a cup of tea Toni and I sit outside in the sun.

Toni wants to know if I’ve told my parents about her.

“What they say, Terr-ee?”

“My mother say I must be careful of Italian girls.”

“For why?”

“She thinks all Italian girls are tarts.”

“What is tarts?”

“Prostitute.”

She bursts into a giggle. “Me, prostitute?”

“No, no, she is just telling me to be careful.”

“You tell her I am a good girl?”

“Yes.”

“What she say?”

“I haven’t had any reply yet, maybe in the next letter.”

I daren’t tell her my mother thought all foreigners were ridden with disease and you caught it off lavatory seats. “If you shake hands with them, try and wear gloves.” But then my mother thought that Mussolini was good for the Italians.

Bill Hall clowning in Mestre – a dismal failure.

Bill Hall is in a playful mood. He drapes a curtain over his shoulder and plays salon music, ‘Flowers in May’, etc.

He is interrupted by the manager, Mr Marcini with his goatee beard and goatee moustache. In fact, he had a goatee head and goatee body. Bowing and nodding, he asks if we like to hear some folklore music. A chorus of ayes. He produces a mountain bagpiper. He’s like a man from another age: he wears a Tyrolean hat, a red shirt with a brocade waistcoat, navy blue breeches to the knee, then leggings bound with goat hide strips. He plays his bagpipes, which sound like the sweet-sounding Northumbrian and gives us traditional tarantellas, marches, etc. It was an hour of great music and I realized that I was watching the last of the old Italy. The old Italy that was to be swamped with tourists, deafened by pop music and Lambrettas. Eventually, Bill Hall joined in on the violin. It was great stuff. When he’d finished, we had a whip-round for the piper and he departed well pleased. Mulgrew thinks he is a Scottish soldier on the run from the Military Police. “It’s a perfect disguise,” he says. “I tell you the hills around here are full of squaddies on the trot from the police. You see those Italian women with hairy legs, they’re squaddies on the trot.”

We are left to fossilize in Mestre while the powers that be plot our destiny. Meanwhile we live a sybaritic life, just mooching all day.

MOTHER:

Where have you been at this time of night?

SPIKE:

I’ve been out mooching, Mother.

∗

“I think they’ve forgotten us,” says Hall.

“Forgotten us, FORGOTTEN?” says Bornheim. “They’ve never

heard

of us.”

I break the boredom by trying to snog with Toni whenever the opportunity presents itself, which is only all the time, and that doesn’t seem enough. Lieutenant Priest tries to find out what the score is. He phones Army Welfare Service in Naples and this is what it sounded like.

∗

Lt priest: Yes, sir…yes, sir…Mestre, sir…but…yes, sir…yes, sir…yes, sir…very good, sir.