Pearl Harbor Christmas (25 page)

Read Pearl Harbor Christmas Online

Authors: Stanley Weintraub

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #United States, #20th Century

The PM described his two major speeches to Attlee, reported worldwide, as “extremely hard exertion” in “such an electric atmosphere.” He had the added burden of Canadian relations with the Vichy puppet government in the immediate aftermath of the Gaullist takeover of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. Rather than capitulate to the Germans, he declared to the Parliament in Ottawa, the French should have held out in their overseas empire:

If they had done this, Italy might have been driven out of the war before the end of 1940, and France would have held her place as a nation in the councils of the Allies and at the conference table of the victors. But their generals misled them. When I warned them that Britain would fight alone whatever they did, their generals told their Prime Minister and his divided Cabinet, “In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.” Some chicken! Some neck!

Churchill’s audience exploded in laughter and applause. He had defused, at least in Canada, the issue of the two islets.

Returning to his review of contentious British-French relations, he quoted Harry Lauder’s serio-comic song about the “last war”:

If we all look back on the history of the past

We can tell just where we are.

Then he turned to the present—to “the period of consolidation, of combination, and of final preparation” gathering combined strength for defeating the enemies and liberating conquered peoples and territories. The next phase, he contended, would be the days of deliverance—the “terrible reckoning.” With optimism belied by the facts on the ground he predicted that he was “looking forward to ’43 to roll tanks off ships at different points all around Europe in countries held by the Germans, getting rifles into the hands of the people themselves, making it impossible for Germany to defend different countries she has overrun.” Then, more cautiously, he added, ignoring the dates he had assigned to recovery and victory,

We must never forget that the power of the enemy, and the action of the enemy, may at every stage affect our fortunes.... I have not attempted to assign any time-limits to the various phases. These time-limits depend upon our exertions, upon our achievements, and on the hazardous and uncertain course of the war.

Parliament was doubly impressed that he delivered his address first in English and again in French, winning the hearts of the French Canadians. Quebecois felt closer to Paris, however jackbooted, than to London, and the curfew, they knew, had been leniently moved back for Christmas and New Year’s Eve, a reward from the Germans for a compliant population.

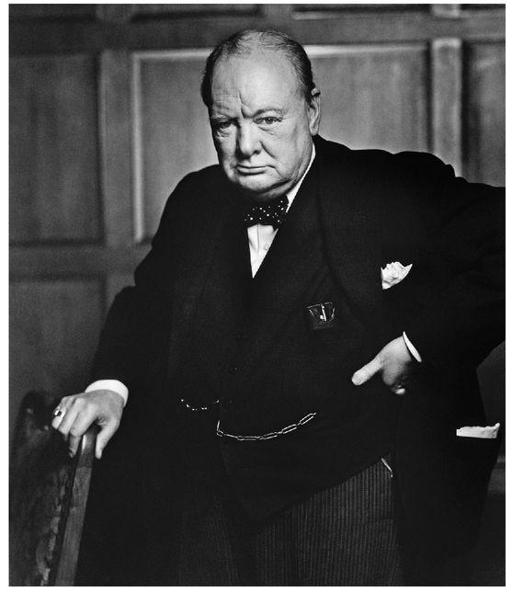

Unexpectedly to Churchill, he had drawn the interest of an Armenian Turk who was already Ottawa’s most brilliant artist in any genre. Yousuf Karsh, thirty-three, was the brother of Malak Karsh, already known for a photo of logs floating down a river that became the striking image on the Canadian one-dollar bill. Yousuf, a portrait photographer, had opened a studio in the Château Laurier Hotel, close to Parliament House, and was already known for capturing the eminent on his 8 × 10 Calumet bellows camera. A

Sunday Times

journalist would remark that “when the famous start thinking of immortality, they call for Karsh of Ottawa.”

The PM was weary after his exertions, Karsh recalled, and “in no mood for portraiture and two minutes were all that he would allow me as he passed from the House of Commons chamber to an anteroom. Two niggardly minutes in which I must try to put on film a man who had already written or inspired a library of books, baffled all his biographers, filled the world with his fame, and me, on this occasion, with dread.”

Churchill paused warily, “regarding my camera as he might regard the German enemy.” The PM’s glowering resentment at being trapped for a portrait seemed exactly what Karsh wanted to achieve, and he was satisfied; although Churchill sulkily ignored the ashtray set before him. As the cigar clamped between the PM’s teeth seemed at odds with the magisterial moment, “instinctively, I removed the cigar. At this the Churchillian scowl deepened, the head was thrust forward belligerently, and the hand placed on the hip in an attitude of anger.” Karsh clicked the lens for an exposure of a tenth of a second. It took some airbrushing to make the background more luminous, the sitter less tired-looking, and his hands softened. The bulldog scowl became one of the most memorable portrait images in history.

Yousuf Karsh’s iconic “bulldog” photo portrait of Winston Churchill, Ottawa, Canada, December 30, 1941.

Photograph by Yousuf Karsh, Camera Press, London

IN WASHINGTON at 4:05 P.M. the President opened his final press conference of the year, this time without Churchill at his side. He pointed to his nearly empty workbasket, indicating no important announcements. “Isn’t that basket rather good for these days?” he remarked. Asked about a “reorganization” of civilian defense (“What about LaGuardia remaining?”), he was noncommittal about “individual personalities.” Fiorello LaGuardia, however colorful as mayor of New York City, had proved unable to carry on two jobs at once and was under fire from Congress and the media. Within the week he would be left with an honorific title and effectively replaced.

“Mr. President, does the Army propose to accept the offer of Colonel Lindbergh for active service?”

“I haven’t heard anything about it,” said Roosevelt, cutting off that line of inquiry. The icon of the isolationist America First Committee and its platform star, Charles Lindbergh, in mid-September, appealing to a national radio audience from Des Moines, Iowa, had made the most notorious speech of his life. Attacking Roosevelt, the British, and the Jews, he deplored Nazi anti-Semitism while criticizing American Jews for urging all possible help to Britain to defeat Germany. Hitler’s Germany was not America’s problem. Jews were. “The greatest danger to this country,” he charged, “lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government.” Roosevelt, he declared, was a pro-war puppet of the Jews. With that the aviation hero self-destructed, and with Pearl Harbor, so did America First.

8

Other questions came up, from Lend-Lease to war budgets to making summer Daylight Saving Time year-round to conserve electric power. To many of them he parried, “You’ll spoil my [State of the Union] Message to Congress if I tell you that.” The minutes note “(Laughter).”

December 31, 1941

New Year’s Eve

K

AMPAR, A VILLAGE BELOW IPOH on the western side of Malaya, was held by survivors of the 15th Indian Brigade, who resisted stubbornly as the Japanese pushed south of the Perak River through rubber plantations and jungle. In a seized open auto, on roads so poor as to be almost nonexistent, Colonel Tsuji had left Ipoh the day before with three men, a light machine gun, and a mosquito net, essential everywhere. “Intending to share a glass of wine with the troops on the line to celebrate the New Year on the battlefield,” he wrote, “we ran about fifty kilometres. Suddenly we ran into heavy shellfire. . . . It was coming from enemy guns in the mountains which constitute Malaya’s spinal column, which lay across the main road.... Even after the position of the enemy guns was located it was very difficult to silence them owing to their concealment in the jungle.” Tsuji soon came upon the captain of a company of small tanks and ordered him forward. “Yes, I understand,” he said, and moved into the smoke of the barrage. “Clear of the burning shells, the tanks were soon, like snails, scrambling up the slope of the enemy’s fortified position, giving great encouragement to our front-line infantry.”

Behind the action, the wine camaraderie forgotten, Tsuji and his men huddled in their car under mosquito netting as it grew dark. “We were completely fagged out, and were just going off to sleep when a shellburst lifted our car off the ground. I told the driver to move a hundred metres to the rear, and we got into another position which seemed safe. We were just dozing off again when another shell landed just beside us. I said, ‘Well, we better move back a bit more.’The shellfire however seemed to follow the car, and no sooner did we move to a new position than we would have to shift to another one.” But the defenses were gradually giving way. The British forces had no tanks and no heavy artillery.

ON THE

Nagato

in Kure harbor, Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, commander of the Pearl Harbor strike force’s Second Division, came aboard at 11:30 to brief Admiral Ugaki. Yamaguchi had aerial photographs taken from his planes showing warships capsized or crippled in the harbor as well as photos of “damages on Wake Island”—evidently prior to its occupation. He was in “very high spirits” yet displeased about the fleet’s “return movement,” left unexplained in Ugaki’s diary. “Though it agrees with what I thought,” he wrote, “it is considered better not to mention [details] here.”

To Ugaki, the major question left after the two sweeps of the Pearl Harbor area had been whether a third strike should have been ordered.

Kido Butai’

s air strength was little depleted, and American sea and air pursuit was unlikely from a demoralized and badly damaged enemy that had undergone three hours of Sunday morning attacks. Admirals Ryunosuke Kusaka and Chuichi Nagumo were conferring about whether to send planes up again when the leader of the air assault, Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, landed aboard safely. He was eager to gas up and go after what targets were missed, such as fuel tanks and repair facilities. Even a burglar, Nagumo warned, hesitates to go back for more. The victim had been rudely awakened. In evidence he noted that the flight deck officer of the carrier

Hiryu,

Commander Takahisa Amagai, had seen the results of anti-aircraft fire against second-wave planes that had barely managed to land, or fallen short, into the sea. Ambitiously, Amagai suggested, “We’re not returning to Tokyo; now we’re going to head for San Francisco.”

Nagumo dismissed the boast as brag. He had delivered a disabling blow. Unpersuaded, Fuchida recommended going back to Oahu, but Kusaka pointed out that the aircraft carriers not located in the harbor posed a threat that could materialize at any time. (The carriers

Lexington

and

Enterprise

had been off the west delivering aircraft to Midway and Wake.) Was the little more they could do worth risking the fleet? Kusaka ordered an immediate turnabout to the northwest, as originally planned. “The attack is terminated,” he said. “We are withdrawing.” Shortly after one o’clock Hawaiian time (nine in the morning the next day in Japan),

Kido Butai

swung about. At Kure, learning of the decision, Admiral Yamamoto, chief architect of the operation, had mixed feelings, as would Ugaki. On his flagship

Nagato,

Yamamoto, a compulsive gambler, composed a sardonic

waka

. A classical verse form of thirty-one syllables arranged in five lines, it was adapted to his love for bridge, which he had learned when a naval attaché at the Japanese embassy in Washington in the 1920s:

What I have achieved.

Is far from a grand slam,

Let me in all modesty declare.

It is more like

A redoubled bid just made.