Pearl Harbour - A novel of December 8th (12 page)

Read Pearl Harbour - A novel of December 8th Online

Authors: Newt Gingrich,William R. Forstchen

Tags: #Alternate history

“Jesus Christ, they’re shooting at us!” someone screamed.

James caught a glimpse of some of the civilian refugees on the deck, who had been casually strolling about watching the approach of the fighter plane with interest, begin to scatter.

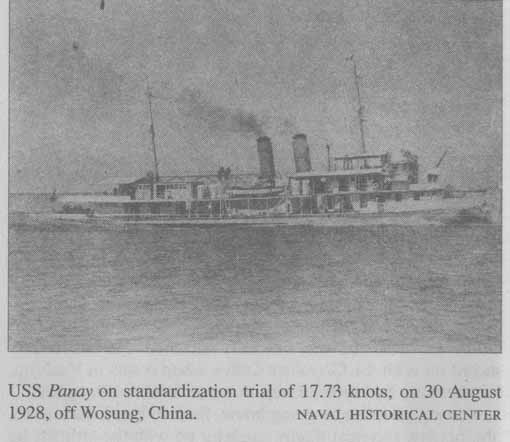

The fountains of water “walked” right into the Panay and suddenly there was the sound, the machine-gun firing, the roar of the plane’s engine, the sound of bullets smacking into steel, ricocheting off, huge flecks of paint flying up, pockmarking the hull, and then the main deck cabin, windowpanes shattering.

The plane bore in, then roared overhead, the red rising sun painted beneath each wing.

The lieutenant stood, gape mouthed, unable to respond for a moment. “They’re shooting at us ...,” he gasped finally, unbelievingly.

James felt, for a brief instant, a strange, almost surreal detachment from it all. Part of his mind refused to believe that this was happening at all, that the Japanese would dare actually attack an American ship. He spared a glance aft. The American flag was standing out in the noonday breeze ... there was another flag painted atop the main deck cabin to clearly identify the ship from the air. No, it couldn’t be ... and yet even as his mind rebelled, he saw the second plane leveling off just above the water, boring in, again the fountainlike geysers kicking up, this time coming straight at him.

And the strangest of thoughts then struck him. I’ve been in the Navy for over twenty-three years and this is the first time, the first time I’m actually being shot at. They are trying to kill me!

There was no melodramatic instant of life flashing before his eyes, thoughts of Margaret, or even of his lost son, just that each geyser erupting was stepping closer, marking the converging fire of 7.7-millimeter machine guns coming right at him.

Someone knocked him hard, sending him sprawling, knocking the wind out of him. It was the lieutenant, finally reacting. The bullets stitched up the hull, tearing up deck planking on the diminutive bridge, shattering more glass, sparks flying. The plane roared over, followed by another right behind it, strafing the bow. He caught a glimpse of a sailor doubling over, collapsing. Screaming now, civilians scattering in panic around the deck, sailors, some moving to their general quarters position, though it had not yet been sounded, others just standing like statues, as unbelieving as James had been.

The three planes soared upward, gaining altitude, and for a moment he thought that somehow, just somehow it was a mistake, that they would climb out, realize their error, and leave. But no, the lead plane did a wingover, now coming down steeply from several thousand feet, guns again firing.

“General quarters!” He heard the order picked up, shouted, men running.

How many drills had he been through aboard ships such as the Maryland, the Lexington, the Oklahoma, where it was all done so smoothly in such orderly, almost stately fashion ... but they had never been under fire, so caught by surprise ... by terror.

The lieutenant was back up on his feet, someone tossing him a helmet, as if it would actually do any good.

“Sir, could you get those civilians under control... get them below decks!”

James came to his feet, not sure where to start; it was not as if he could pass a simple order and they would all just follow along.

The lead plane was firing again, shot plunging down, several more dropping, including one of the civilians, which set off hysterical screaming, the plane roaring out low over the water and then immediately beginning to climb back up.

“Below, damn it, below!” James shouted. Grabbing the nearest civilian, he vaguely recognized him as a secretary from the embassy; he shoved the man toward the open doorway of the main deck cabin.

There was a moment’s hesitation, but then the second plane came in for its strafing run, and as one man went below the others raced to the doorway, shoving to get under what James knew was nothing more than the false protection of the overhead deck. The Panay was no battleship; it was a river gunboat.

“Below decks! Below decks!” He stood by the doorway as the last of them piled in, a couple of sailors carrying a man wearing a clerical collar, a missionary knocked unconscious, bleeding profusely from a head wound.

He heard a crack of a rifle, a lone sailor standing on the deck, armed with a Springfield ‘03, swearing, firing as the first plane continued to climb away.

“Bombs!”

He looked up and saw yet another plane, not one of the fighters, now coming down on them, pulling out of its dive, two dots detaching.

He needed no urging. This time he flung himself flat on the deck, only to be met by the hard steel as it was flung upward by the two bombs bracketing the gunboat.

The three fighters wheeled, coming back in for yet another strafing run. Stunned by the blast, soaked by the cascades of water coming down, he suddenly no longer cared, standing back up, filled with rage.

Atop the main cabin he heard someone swearing and, looking up, saw a sailor actually holding an American flag up, waving it, as if the bastards would somehow now see it at last. He started to shout for the man to get the hell down, but his cry was drowned out by the roar of the planes, the staccato snap of bullets, the sailor diving down for cover, flag falling from his hands.

“Abandon ship!”

Startled, he looked back to the young commander of the Panay, hands cupped, shouting the order; but already men were going over the sides. Actually there was no need to do so; the bracketing of the bombs had staved in the fragile hull, and the Panay was already settling to the bottom of the muddy river, water beginning to cascade over the railing. All he had to do was just simply step over and into the Yangtze. The water was cold, damn cold, startling him. A sailor tossed a life jacket to him, which he simply grabbed hold of, to keep afloat, kicking the few yards to the weed-choked river-bank.

Another of the fighters wheeled in like a vulture over a dying beast and rolled in for a strafing dive. James pushed the civilian by his side down into the weeds, diving to get under the muddy water. An instant later it felt like he had been kicked by a horse, shoving him down into the mud, no pain, just numbness. He convulsively gasped, the filthy water of the Yangtze flooding into his lungs.

In four feet of muddy water, he began to drown. He felt hands around him, pulling him up, rolling him over. Panicked, he kicked, struggled, the pain suddenly hitting, agonizing. He vomited, aspirating more water and filth as he did so, choking. He heard voices, someone shouting, still struggling he felt land under him, mud stinking of human waste.

Somebody rolled him on his side, slapping him on the back. Gasping, he was finally able to draw a breath.

“Down!”

More gunfire, a plane racing over low, a split second of shadow passing like an angel or demon of death, the roar of the engine, someone swearing.

“That’s it, sir, take a breath, that’s it!”

The voice was almost gentle. He had lost his glasses, the world looked fuzzy, but he saw the stripes of a chief petty officer who was kneeling over him.

“Let me get your tie off, sir,” and the officer snaked it loose, popping a few buttons off his uniform, taking the tie.

“This might hurt now, sir, hang on.” And damn it did hurt. As the sailor raised James’s left arm, it felt like someone had driven an ice pick up it. Blood was pouring out of his hand. He tried to move it, winced, the last two digits dangling loosely. The sailor wrapped the tie around the hand, tight it felt, too damn tight; he gasped slightly, but said nothing.

“That’ll do for the moment, sir.”

It was still hard to breathe. “Thanks,” was all he could gasp out.

“I’m going back in now, sir, there’re still people out there. Stay low.”

James could only nod, suddenly feeling small, helpless. As with anyone with astigmatism, the loss of glasses made him feel naked, vulnerable. My other glasses, in my luggage. He looked up, absurd. Panay was settled to the gunwales, smoke pouring out of her.

“I can’t believe it,” the petty officer gasped, “the bastards. I can’t believe it.” One of the fighters banked over low, circling, and he could catch a glimpse of the pilot in the open cockpit looking down.

The petty officer stood up, raised his arm in the classic gesture of insult, finger extended, shouting obscenities.

James said nothing, looking up, at the circling plane, the face of the enemy above him.

We’re at war now, he thought. America would never accept this, could never accept this. They had fired on the flag, on a ship of the United States Navy. It could only mean one response now--war.

The White House Washington, D.C.: 14 December 1937

“Sir, I know you are furious about this Japanese attack on the Panay, but there is just nothing practical we can do about it,” Secretary of State Hull wearily asserted to an angry President Roosevelt.

“Cordell, this is my navy, and they have sunk one of my gunboats. We have to do something.”

“Mr. President, Gallup reports 70 percent of the American people want us to withdraw from China, not just the military, but everyone, every civilian, every missionary, the logic being if none of us are there, no one can get shot at and thus we avoid a war.”

Disgusted with this bit of intelligence and the logic it implied, the president could only wearily shake his head.

“Congress is even more isolationist than the American people. There would be no congressional support for a real confrontation with Japan. The American people oppose the Japanese aggression and sympathize with the Chinese, but they simply do not want to get involved.”

“You may be right for now, but I have a feeling time is going to teach all of us some very painful lessons about aggressive dictatorships in both Tokyo and Berlin. For the moment, you are right. You and Joe Grew work up some strong statement, and raise as much Cain with the Japanese as you can without getting us into a shooting match.”

As Hull turned to leave, FDR couldn’t resist one last parting shot. “Just remember that I am going to watch them constantly and take advantage of every mistake they make to teach the American people that we have to stop the dictatorships before they threaten us directly.”

Nanking, China: 15December 1937

Staggering with exhaustion, Cecil Stanford, correspondent for the Manchester Daily, pushed through the terrified, jostling mob. Attached to a bamboo pole, held aloft in his right hand, was a makeshift British flag, painted onto a torn bedsheet. In his other arm, nestled in tight against his breast, two small Chinese girls, ages most likely about two, both of them soiled, covered in feces and vomit, both screaming hysterically even as they clung to him. Clutched around him were several score of people, terrified, pressing in tight, all but climbing on top of him, petrified to be at the edge of the group staggering through hell.

The children had been pressed into his arms a couple of blocks back; a woman, horrific looking, blood pouring in rivulets down both her legs, had staggered up to him. The cause of the bleeding was obvious, far too obvious because she was naked. She had pressed the two screaming children into his arms, staggered back away, and collapsed in the gutter.

They turned the comer, his goal only a few blocks away, and there they were--half a dozen Japanese soldiers.

They were obviously drunk, whether drunk on liquor, drugs, or some primal insanity was immaterial now. He braced himself, unashamed to inwardly admit that he was terrified. If only Winston could see him now, what would he think of his choice of “spies”? For that matter, if Winston could see, at this moment, the goddamn nightmare of this city, what would he say, what would the entire world say?

He had come to Nanking shortly after the incident at the Marco Polo Bridge up in Peking, since it was the purported capital of the Nationalist forces.

The bridge incident had exploded into what was officially being called the “Second Sino-Japanese War,” a polite reference to the fact that the two sides had a brief skirmish back in 1894-95. But that war had been fought with at least some dignity; this, this was beyond any imagining, beyond anything he had believed in and loved about the Japanese.

Within weeks after the takeover of Peking, Japanese armored columns had poured into the central China plains, the forces of Chiang Kai-shek ineffective at best, cowardly at worst. Four weeks ago he had been in Shanghai, covering events there, but felt it best to try to make it back to the temporary capital, perhaps to even seek out an interview with Chiang Kai-shek. To no avail.

The siege of the city had caught him and nearly all the defenders of the ancient walled city off guard, the Japanese army rushing forward with lightning speed. In less than three days the defenses had crumbled, and the Japanese army had poured in. For a few brief hours, very brief hours, there had been an uneasy tension, Japanese commanders purportedly declaring that they came as liberators, that personal property and rights would be respected, but that fleeing soldiers disguised as civilians must be turned in. And then, it seemed in a matter of hours or minutes, the army had given itself over to a medieval pillage, the likes of which transcended Cecil’s worst nightmares.