Pediatric Examination and Board Review (11 page)

Read Pediatric Examination and Board Review Online

Authors: Robert Daum,Jason Canel

4.

(A)

5.

(D)

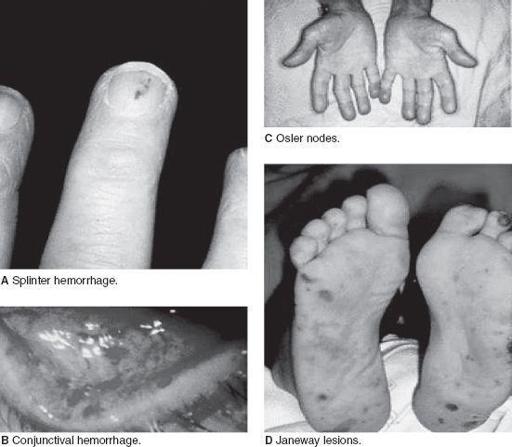

Although there is no specific diagnostic laboratory test for rheumatic fever, the diagnosis is based on the Jones criteria. These are separated into major and minor manifestations. Major criteria include polyarthritis, carditis, erythema marginatum, subcutaneous nodules, and chorea. The most common manifestation is polyarthritis occurring in up to 70% of patients, typically a migratory arthritis involving the large joints (knees, hips, ankles, elbows), which characteristically responds dramatically to salicylate therapy. Carditis occurs in approximately 50% of cases and includes myocarditis, pericardial effusions, arrhythmias, and valvular heart disease. Erythema marginatum (

Figure 4-1

) occurs in less than 10% of patients and is a nonpruritic serpiginous rash that occurs on the torso and is almost never seen on the face. The rash is evanescent and becomes more apparent following hot baths or being wrapped in warm blankets. Subcutaneous nodules are nontender, freely mobile nodules occurring usually over the bony surfaces of the elbows, wrists, shins, knees, ankles, and spine. They occur in 2-10% of cases. Chorea occurs in up to 15% of cases and is a neuropsychiatric disorder that may include choreiform movements, hypotonia, emotional lability, anxiety, and an obsessive-compulsive disorder. Chorea usually occurs late, after the initial pharyngitis with the average time to onset of about 6-7 months. It may last as long as 18 months. Recent evidence suggests that chorea is associated with the presence of antineuronal antibodies. Minor manifestations include fever, arthralgias (when polyarthritis is not present), increased acute phase reactants such as CRP, and a prolonged PR interval on ECG (in the absence of other evidence of carditis). The diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever is made with either 2 major manifestations or with a single major manifestation and 2 minor manifestations. If made by 1 major manifestation and 2 minors, the diagnosis should be supported by evidence of a preceding streptococcal infection either by a positive throat culture or by rising streptococcal antibody titers (eg, antistreptolysin O). There are 3 exceptions to the Jones criteria for diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever:

1. Chorea may be the only manifestation of rheumatic fever.

2. Indolent carditis may be the only manifestation in patients following the initial infection.

3. Recurrences often do not strictly fulfill the Jones criteria. Therefore, a presumptive diagnosis of recurrent rheumatic fever may be made with fewer than the usual number of criteria. Recurrent disease should only be diagnosed if there is supporting evidence of a recent streptococcal infection.

FIGURE 4-1.

Erythema marginatum on the trunk of an 8-year old caucasian boy. The pen mark shows the location of the rash approximately 60 minutes previously. (Reproduced, with permission, from Fuster V, O’Rourke RA, Walsh RA, et al. Hurst’s the Heart. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008:1694.)

6.

(C)

Treatment for acute rheumatic fever includes therapy directed at the streptococcal infection with penicillin followed by prevention of recurrences with either twice-daily oral penicillin or oncemonthly IM benzathine penicillin injections. Although some advocate prophylaxis to be continued at least until the patient is 21 years of age, others recommend that prophylaxis be lifelong. In patients who are penicillin allergic, prophylaxis can be substituted with either oral sulfadiazine or erythromycin. Recurrences of acute rheumatic fever usually occur within the first 5 years after the initial diagnosis and are characterized by more severe cardiac valve involvement. It is estimated that approximately 10-25% of patients with heart valve involvement will have complete resolution by 10 years.

7.

(A)

The mitral valve is the most commonly affected followed by the aortic valve and, rarely, the tricuspid or pulmonary valves. Initially, the affected valves develop regurgitation as a result of inflammation and valve dysfunction. However, with healing of the inflammation, long-term development of mitral valve stenosis can occur. This may be seen as early as 2-3 years following the acute episode but usually occurs 10-20 years later.

8.

(A)

The child described most likely has Kawasaki disease, an acute vasculitis of unknown etiology. Kawasaki disease is the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in the United States. The incidence ranges from 2-6/100,000 children and is highest in Asian American children. The peak incidence is at 1-2 years of age with 85% of the cases occurring in children younger than 5 years of age. The disease is uncommon in patients older than 8 years of age or younger than 3 months of age. The clinical manifestations include the presence of fever for at least 5 days, no other reasonable etiology, and 4 of 5 of the following:

1. A nonexudative conjunctivitis that is usually bilateral

2. Erythema of the lips, oral mucosa, and pharynx, including a strawberry tongue and cracking or peeling of the lips later into the disease

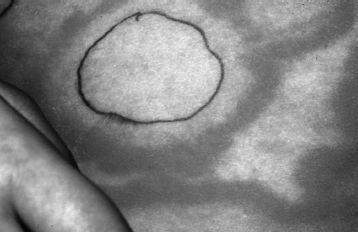

3. A polymorphous rash of the face, trunk, and extremities that later can involve the perineal area and is characterized by desquamation at 5-7 days (

Figure 4-2

)

4. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.5 cm in diameter that is usually unilateral

5. Changes in the extremities, including edema and erythema of the hands and feet followed by periungual desquamation at 11-25 days into the disease

FIGURE 4-2.

Kawasaki disease. Desquamation of the tissue of the palm. (Reproduced, with permission, from Wolff K, Johnson RA. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009: Fig. 14-45.)

Incomplete Kawasaki disease can be diagnosed when fever is present for 5 or longer days in the presence of 2 to 3 of the preceding criteria when the CRP is 3.0 mg/dL or more and/or the ESR is 40 mm/hour or more. In this instance, certain laboratory criteria should be met including hypoalbuminemia, anemia, increased serum alanine aminotransferase, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, and sterile pyuria.

9.

(D)

Other supportive findings of the acute phase of Kawasaki disease include urethritis with sterile pyuria, aseptic meningitis, abdominal pain, hydrops of the gallbladder, and arthritis that usually involves the small joints but may involve the large joints 2-3 weeks into the disease. Also, mild carditis and arrhythmias may occur. The subacute phase occurs 11-25 days following the onset of fever and is characterized by a decrease in the rash and fever with the onset of desquamation of the fingers and toes. Thrombocytosis peaks at 2-4 weeks into the course of the disease. It is during this phase that coronary artery aneurysms usually become evident.

10.

(C)

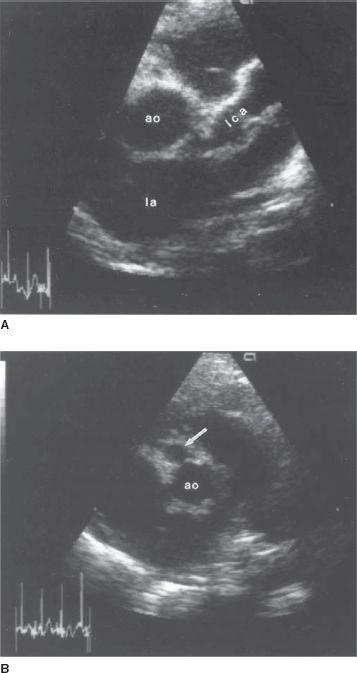

Coronary artery aneurysms are the most feared complication of Kawasaki disease and occur in up to 15-25% of untreated patients (

Figure 4-3

). They are a result of the panvasculitis resulting in aneurysmal transformation of the coronary arteries and may be seen as early as 7 days after the onset of the fever. Their incidence peaks at 3-4 weeks and they are seldom found after 8 weeks into the course of the disease. Giant aneurysms are described as having a diameter greater than 8 mm and are associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Patients with aneurysms also have a higher incidence of developing stenoses leading to myocardial ischemia and infarction with long-term follow-up. Coronary artery rupture is the most common cause of mortality in the subacute phase; myocarditis, heart failure, and arrhythmias are the most common causes of mortality in the acute phase within the first 10 days after the onset of fever. Risk factors for the development of coronary artery aneurysms include male gender, age younger than 1 year, hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL, white blood cell count greater than 30,000/mm

3

, ESR greater than 101 mm/hour, and prolonged fever. Echocardiography is recommended for assessment of coronary artery involvement with Kawasaki disease. The most recent recommendations suggest that an echocardiogram is obtained at diagnosis, and if no coronary disease is seen, then it should be repeated in 6-8 weeks. If coronary artery involvement is documented, then follow-up should be more frequent based on the extent of disease.

11.

(A)

The management of Kawasaki disease includes high-dose aspirin, which is given during the acute phase, followed by low-dose aspirin for 6-8 weeks. This is given for antithrombotic effect while thrombocytosis is present. IVIG is administered within the first 10 days of the disease at a dose of 2 g/kg and may be repeated if fever persists following this therapy. The use of IVIG decreases the incidence of coronary artery aneurysms to less than 5%. If aneurysms persist past 2 months, then aspirin or other anticlotting agents should be continued. The use of steroids is not indicated for uncomplicated Kawasaki disease.

FIGURE 4-3.

Parasternal short-axis images of coronary artery aneurysms associated with Kawasaki disease. A. The proximal left coronary artery (LCA) is diffusely dilated and aneurysmal. B. A proximal right coronary artery aneurysm (

arrow

) is shown. Ao, aorta, LA, left atrium. (Reproduced, with permission, from Fuster V, O’Rourke RA, Walsh RA, et al. Hurst's the Heart, 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Fig. 16-140.)

12.

(A)

The most likely diagnosis in this situation is infective endocarditis. This is an inflammatory disorder of the heart resulting from an infection. The signs and symptoms of infective endocarditis include acute findings of fever, anorexia, weight loss, pallor, night sweats, myalgias, and new onset of a heart murmur, usually as a result of valve disease from infection. Later findings result from embolic phenomena and include splinter hemorrhages, Roth spots (retinal hemorrhages), Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, splenomegaly, clubbing, arthralgias, arthritis, glomerulonephritis, and aseptic meningitis (

Figure 4-4

). The pathogenesis of infective endocarditis results from the initial setting of a jet of blood or turbulence within the heart leading to endothelial damage and formation of a sterile clot or vegetation. This serves as a nidus for bacterial infection.