Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies (40 page)

Read Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies Online

Authors: Catherine E. Burns,Beth Richardson,Cpnp Rn Dns Beth Richardson,Margaret Brady

Tags: #Medical, #Health Care Delivery, #Nursing, #Pediatric & Neonatal, #Pediatrics

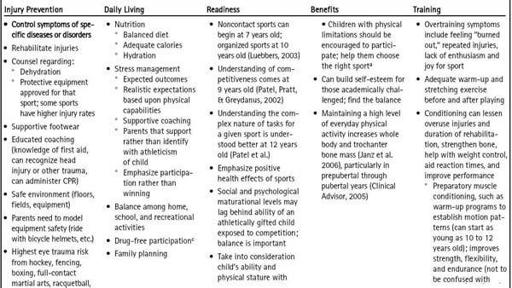

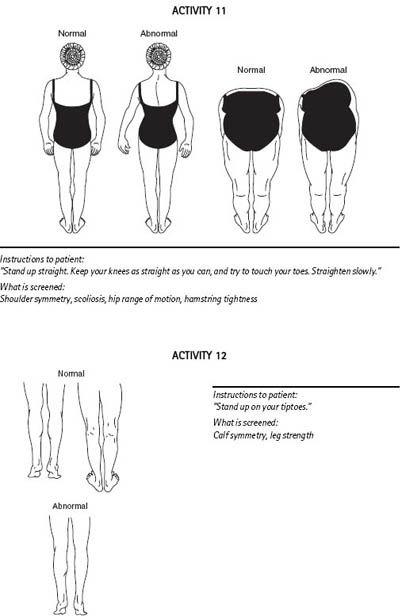

Figure 10-2 Illustration of the 90-second sports musculoskeletal examination.

From

For the practitioner: Orthopaedic screening examination for participation in sports

. © 1981 Ross Products Division, Abbott Laboratories. Text adapted from Garrich, J. G. (1977). Sports medicine.

Pediatric Clinics of North America, 24, 737–747

.

Table 10–2 Example of an Appropriate Preparticipation Physical Examination | |

| Examination Feature | Comments |

| Height and weight | Establish baseline and monitor for eating disorders, steroid abuse. |

| Blood pressure | Assess in the context of participant’s age, height, and sex. |

| General appearance | Excessive height and excessive long-bone growth (arachnodactyly, arm span greater than height, pectus, excavatum) suggest Marfan syndrome. |

| Eyes | Important to detect vision defects that leave one of the eyes with < 20/40 corrected vision. Lens subluxations, severe myopia, retinal detachments, and strabismus are associated with Marfan syndrome. Note any anisometropia for the record. Absence of one eye will limit some sport choices. |

| Cardiovascular | Palpate the point of maximal impulse for increased intensity and displacement, which suggest hypertrophy and failure, respectively. Note heart rate, rhythm. Check for murmurs. A murmur that worsens with standing or Valsalva suggests hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. |

| | Perform auscultation with the patient supine and again with the patient standing or straining during Valsalva maneuver. |

| | Check femoral against radial pulses; femoral pulse diminishment suggests aortic coarctation. |

| Respiratory | Observe for accessory muscle use or prolonged expiration and auscultate for wheezing. Exercise-induced asthma will not produce manifestations on a resting examination and requires exercise testing for diagnosis. |

| Abdominal | Assess for masses, tenderness, organomegaly (especially liver and spleen). In females, assess for any pain and/or enlargement over hypogastric area or pelvis that might suggest pregnancy or gynecologic problem; proceed with further work-up as indicated. |

| Genitourinary | Hernias and varicoceles do not usually preclude sports participation. Check for single, undescended testicle, masses. Discuss testicular cancer and provide information about the self-testicular exam. |

| Musculoskeletal | Use the 90-second musculoskeletal examination (see Figure 10-2 ). Consider supplemental shoulder, knee, and ankle examinations as indicated specific to the chosen sports injury-prone areas. |

| Skin | Evidence of Molluscum cotagiosum , herpes simplex, impetigo, tinea corporis, or scabies would temporarily prohibit participation in sports where direct skin-to-skin compositor contact occurs (e.g., wrestling, martial arts). |

| Neurologic | Gross motor assessment with attention to equality of strength, especially with a history of recurrent stingers or burners, head injury. Usually sufficiently grossly assessed during the 90-second musculoskeletal exam. |

Source: |

Nikola’s hemoglobin is 12.6.

Because this is a female runner with a history of stress fracture, weight loss, questionable adequate caloric intake, and transient oligomenorrhea, you are suspicious for early female athlete triad, but also want to rule out thyroid dysfunction. She has also been sexually active. You add the following tests:

•

TSH: 3.6 UIU/mL (normal: 0.7–6.4 UIU/mL)

•

T4: 1.20 ng/dL (normal: 0.8–2.7 ng/dL)

•

Nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) urine screen: negative

(NAATs have high sensitivity and specificity for chlamydia and gonorrhea with the exception of the PCR type NAAT, which does not detect gonorrhea as well as the other two (Cook, Hutchinson, Ostergaard, Braithwaite, & Ness, 2005).

Making the Diagnosis

What other diagnoses will you consider?

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnoses are secondary to the underlying features of the female athlete triad and include anorexia (malnutrition), leukemia, thyroid disorder, depression and other psychological conditions, osteopenia, osteoporosis, menstrual dysfunction, inadequate sports footwear, anatomical (joint or muscle) factors, osteogenesis imperfecta, early onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and overuse. If the amenorrhea continues despite nutritional and weight correction, you would proceed to explore other diagnostic differentials for this condition covered in other references.

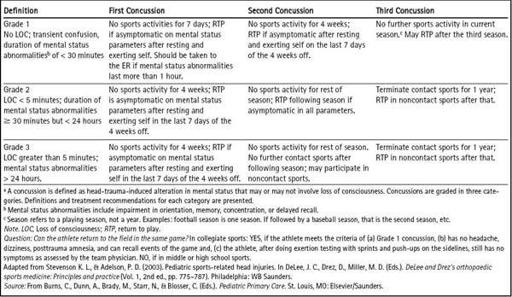

Nikola’s PPE is reassuringly normal, as far as any residual effects from her head injury. She is at risk of second-impact syndrome should she receive another head trauma. If this should happen, it is not likely it would be a result of her noncontact running sport, but could be a result of recreational activities. Before clearing her for sports you need to obtain the prior head injury treatment records, as previously stated. However, based on the criteria listed in

Table 10-3

, you surmise it will be doubtful that she would be limited in her ability to run.

Because she is female, she is not as likely to suffer from sudden death as are males, and her review of systems and cardiac examination were all normal. Your review of the criteria suggestive of potential sudden death was also negative. Her murmur is typical of that of an innocent murmur, and no further workup is required.

Aspects of Nikola’s examination prompt you to weigh heavily her need to ensure she is obtaining adequate nutritional calories to meet her energy and sex steroids needs, and thus avoid full-blown manifestations of the female athlete triad. Her headaches are controlled; no further workup is necessary unless they worsen or become more debilitating.

Table 10–3 Recommendations for Management of Concussiona in Sports

Management

General Management Strategies

The prevention of injury is not necessarily the most important aspect of PPE management. There are a myriad of health-related topics that should be taken into consideration, as discussed earlier. The provider will need to perform an assessment regarding developmental readiness and the type of preseason conditioning needed.

Table 10-4

lists training (conditioning) and other management strategies the provider can recommend.

Educating coaches, parents, and the individual about heat illness (hyperthermia) prevention is important, especially for those participating in high performance recreational activities. See

Table 10-4

.

Active teenagers need to exceed their baseline caloric needs by 1,500 to 3,000 calories, depending upon the sport. Children require an intake of 60 kcal/kg of ideal body weight per day to maintain normal growth. The daily caloric needs consist of:

• Carbohydrates (CHO): 55% to 75%

• Fats: 25% to 30%

• Protein: 15% to 20%

Women need to ensure adequate iron and calcium intake and may need supplements to achieve adequate levels of both. Calcium intake should be 1,200–1,500 mg/day for all youth.

Different sports involve the use of different fuel sources. Short-term, high-intensity sports (e.g., high jumping, diving) use anaerobic fuel sources, such as carbohydrates. Long-term activities (e.g., running, cross-country skiing) involve aerobic fuel sources, such as carbohydrates (both an aerobic and anaerobic source), protein, and fats. The carbohydrates should come from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and milk sugars rather than from processed sugar sources. Carbohydrate loading prior to an activity has not been studied in children nor has it proven to enhance performance (Blosser, 2009). However, for activities that last longer than one hour, performance has shown improvement with carbohydrate intake. Additionally, muscle glycogen resynthesis is improved with the intake of CHOs if taken 30 minutes and 2 hours after strenuous activity. Additional protein may be efficacious for intense endurance sports and strength training (1,500 to 3,000 kcal above the recommended daily allowance of 1 g/kg/day). It is important to counsel that eating additional protein should not replace necessary CHOs and fats; extra fat will be stored from excessive, unused protein.

Some athletes (notably wrestlers) may practice weight cycling (weight loss). This practice has not been shown to lead to long-term adverse effects or to affect height and weight; however, it can deplete electrolytes; affect glycogen stores, hormones, and nutrition status; impair mental and academic performance; reduce immunity; and cause pulmonary emboli and pancreatitis (Housh & Johns, 2001). The practice should be discouraged; it is a risk factor for longer term dysfunctional eating. Other rapid weight loss measures practiced by athletes may include removing fluids from the body via sauna or a sweat suit, laxatives, diuretics, diet pills, licit or illicit drugs, nicotine, prolonged fasting, overexercising, or vomiting (Blosser, 2009).

Table 10–4 Management Strategies for the PPE