Peeps at Many Lands: Ancient Rome (Yesterday's Classics) (3 page)

Read Peeps at Many Lands: Ancient Rome (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: James Baikie

Tags: #History

Now whether Proculus Julius were merely a deceiver, who told his story to turn away suspicion from the murderers of Romulus, or whether he really believed that he had seen and heard that which he declared to the citizens, may not be lightly determined. Only this one thing do we know assuredly, that the promise made by heaven through him, if indeed heaven spake by his lips, has been fulfilled in such fashion that no man may gainsay it.

A Fight for Freedom

A

FTER

Romulus had gone from among men, there followed him, as rulers upon the throne of Rome, six other kings. Some of them were good men and true, and some were rather warlike and tyrannous than good; but under them all the city grew and waxed mighty, till all the neighbouring land owned its dominion. Now the last of these kings, Lucius Tarquinius by name, called also "Superbus," or "The Proud," because of his arrogance, was not of Roman but of Etruscan descent; for his ancestors had been but simple Etruscan squires before his grandsire Tarquinius Priscus came to Rome and climbed to the throne. Tarquin the Proud was a good soldier and a strong ruler, but he had not learned to rule his own house, and his sons were wild and wicked men, who denied themselves nothing that their eyes coveted or their hearts desired. And, in especial, one of them, Sextus Tarquin, wrought foul wrong to Lucretia, wife of a noble Roman named Collatinus, while her husband was fighting for Rome at the siege of Ardea.

Then Lucretia summoned her husband and his friends from the camp at Ardea, and when she had told them the story of the bitter wrong that Sextus Tarquin had wrought, she struck a knife into her heart, and so died before them all, preferring death to a dishonoured life. Then Collatinus, and Brutus his friend, who was near of kin to the King, and all that had heard the dreadful story of Lucretia, took oath to submit no longer to the tyranny and cruelty of the Tarquins; and so, stirring up the whole city by the recital of the wrongs of Lucretia, and the sight of her dead body, they raised revolt and declared Tarquin the Proud deposed. And when the King came in haste from the camp to quell the revolt, he found the gates shut against him, and behind him the army which he had left, stirred up by Brutus, joined the rebellion and drove out the younger Tarquins. So the King and his whole evil brood were forced to flee from Rome, and they betook themselves for help to the Etruscans, from whom they were sprung. But the evil Sextus, fleeing to the town of Gabii, which he counted his own domain, was there brought to his deserved end, in revenge for all the rapines and murders which he had wrought.

So the whole race of kings—nay, also the very idea of kingship—was cast out from Rome, as hateful and not to be endured; and the great city became a republic, governed by a council of three hundred of its greatest and wisest men, who were called the Senate, while the chief officers of the State, who governed in place of the King, were two men chosen from among the honourable men of the city, and called Consuls. They held office only for a year, that so no man might ever become too mighty for the safety of the city, or might dream of setting up the kingship again.

But Tarquin the Proud and his sons were by no means minded to give up their State and power without a struggle. So first they allied themselves with the men of Veii, and made war on Rome, and when the battle went against them they turned to the great King Lars Porsenna of Clusium; and because kings like not that the subjects of other kings should by rebellion set a bad example to their own subjects, Porsenna gathered all the might of the Etruscans and marched into Roman territory to restore the Tarquins. And in the war that came of his adventure there were many noble passages of arms and deeds of daring, so that this war remained for ever noteworthy to the people of Rome.

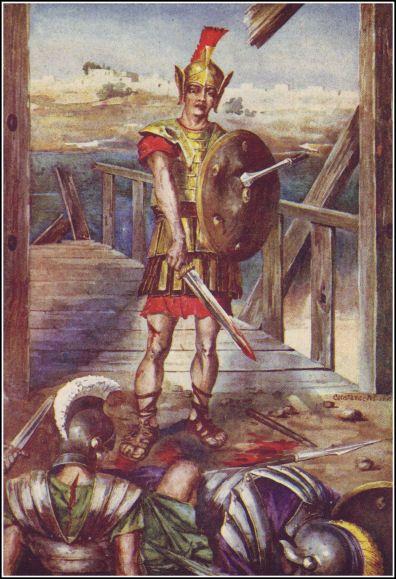

For the army of Porsenna was greater than that the Romans might meet it on the open field; wherefore they withdrew within the walls, leaving a guard in the fort called Janiculum, on the farther side of Tiber, to cover the approach to the wooden bridge (called the Sublician Bridge, because it was built on piles), by which alone the enemy might cross. But the great host of the Etruscans stormed Janiculum, and slew the men who held it, and for awhile it seemed that naught could keep them from crossing the bridge and sacking Rome. Then one brave Roman, named Horatius Cocles, ran to the bridge-head, shouting as he went to those behind to hew down the bridge while he held back the enemy, and calling for two others to stand beside him in the narrow way and keep the passage. So Spurius Lartius and Titus Herminius followed him, and took their stand, the one on his right hand and the other on his left, so that the three shields blocked the whole way, and none might pass to the bridge without venturing on the swords of the three champions of Rome.

The Etruscans, brave men also, sent chosen warriors to the assault again and again, but numbers were of no avail in so narrow a pass, and the three Romans proved more than a match for any three of their enemies, so that at last the ground before the keepers of the bridge was cumbered with the slain. Meanwhile the Romans behind were hewing with all their strength at the bridge; and when he saw that it was just about to fall, Horatius ordered his companions to retire and save themselves. But he himself remained alone before the bridge-head, scornfully defying the whole Etruscan army, and catching on his shield the javelins which they cast against him. Then from behind him came the crash of the falling bridge, and the shout of the exulting Romans, who saw their city saved, and Horatius, raising his sword to heaven, cried, "Tiberinus, holy father, I pray thee to receive into thy kindly stream these weapons and this thy warrior." So saying, he plunged into the river, and, heavily armed and sore wounded as he was, swam safely across to his friends. And great awe fell upon the Etruscans, and the Romans, in gratitude to him who had saved them, set up his statue in the Comitium, or place of assembly, and bestowed upon him out of the common lands as much land as he could plough in one day.

HORATIUS KEEPS THE BRIDGE

As for the many other brave deeds which marked this struggle with Lars Porsenna, as that of Mucius Scaevola, who burned his right hand in the fire that the Etruscan King might learn how vain it was to think of forcing him to tell the secrets of the Roman plans, or that of the maiden hostage Clœlia, who swam the Tiber and escaped—to recount all these would take over long, so this of Horatius and the bridge must suffice. And in the end it fell out that the Etruscan King, despairing to take Rome, consented to withdraw his army and to make terms of peace; and the Tarquins still remained in exile.

Yet still another attempt to bring back the tyrants was made by the thirty Latin cities, under the command of the Prince Octavius Mamilius, son-in-law of King Tarquin. The battle was joined near by the Lake Regillus in the land of Tusculum, and the fighting was fierce and stubborn. Valerius, one of the Roman Consuls, was slain, and in the fight around his dead body, Herminius, one of those who had kept the bridge along with Horatius, slew the Prince Mamilius, but was himself slain as he stooped to take the spoils of his dead foe. Now the legend says that in the thickest of the fight, when the Romans were hard bested, and the Dictator, Aulus Postumius, was about to head another charge on the Latin ranks, he became suddenly aware of a pair of warriors who rode beside him.

"So like they were, no mortal

Might one from other know.

White as snow their armour was;

Their steeds were white as snow.

Never on earthly anvil

Did such rare armour gleam;

And never did such gallant steeds

Drink of an earthly stream."

Behind these strange champions the Romans charged, and not all the bravery of the Latins could withstand their onset. The standards of the thirty cities were swept away like straws on a flooded stream, and the last hopes of the Tarquins were drowned in blood.

Then it came to pass that the same evening, as Sempronius Atratinus, who had been left in command at Rome, was watching on the walls, he saw two horsemen spurring towards the city.

"So like they were, man never

Saw twins so like before;

Red with gore their armour was,

Their steeds were red with gore."

They gave to the anxious citizens the news that on that very day the thirty Latin cities had been vanquished by the Roman arms. Then they rode slowly on to the Forum amidst the shouts of the people, while laurel wreaths were showered upon them; but no man dared to ask who they might be. At last they came to the Pool of Juturna, in the Forum, hard by the temple of Vesta.

"When they drew nigh to Vesta,

They vaulted down amain,

And washed their horses in the well

That springs by Vesta's fane.

And straight again they mounted,

And rode to Vesta's door;

Then, like a blast, away they passed,

And no man saw them more."

Then all men knew that these strange horsemen, victors at Lake Regillus, and messengers of victory almost in the same hour at Rome, were none other than the great Twin Brethren of the gods, Castor and Pollux, whose stars shine high in the eastern heavens in the winter nights of Rome. And great honour was done to them, and a feast was decreed to be observed each year on the day when the great battle by Lake Regillus was fought and won. So ended the last attempt to restore the kingship in Rome, and the city was left to her freedom and her growth.

The Roman Army

"G

O,"

said Romulus, when he appeared as a god to the trembling Roman Senator, Proculus Julius—"go, tell the Romans that it is the will of heaven that my Rome should be the head of the world. Let them henceforth cultivate the arts of war, and let them know assuredly, and hand down the knowledge to posterity, that no human might can withstand the arms of Rome." Never did a prophecy more thoroughly bring about its own fulfilment than this, if it were ever made. For centuries the Romans obeyed their founder, and cultivated the arts of war, till they were heads of the world, as Romulus predicted; and for centuries they cultivated no other arts but those of war, which was not so well either for them or for the world. In fact, it brought about Rome's ruin in the end, for the conquest of the Eastern world brought all the opportunities of luxury to men who had never been trained to appreciate beauty and splendour at their true value, and the rough, ignorant Roman ran riot in luxury till he was thoroughly corrupted by it, instead of using his new treasures with moderation and understanding, as a better instructed man would have done.

However, there can be no doubt of the success with which the arts of war were cultivated. Rome lived by and for her army; she made it the most perfect instrument of war that the world had ever seen, and, while she sometimes used it with brutal cruelty, it proved also, many a time, the school of all those virtues of steadfastness, and devotion to duty, and impregnable courage, which we have learned to associate with the Roman name. Her army, nine times out of ten, showed all that was best in Rome; only very rarely did it show the worst.

Further, we must realize that it was really the army that did the work. For, though Rome was so great a military power, her generals were very rarely of the first class. Julius Caesar, of course, will always stand beside Alexander and Hannibal and Napoleon as one of the world's supreme captains, but no other Roman can be named as worthy to hold place beside him. The successful Roman general was usually a competent soldier, and little more; given competency, his magnificent infantry attended to the rest. The unsuccessful Roman general was very often a miracle of incompetency—indeed, he must have been, to make so miserable a use of his splendid material. Nor was the incompetent general by any means a rarity, as the many bloody defeats sustained by the legions, in spite of their steady valour, clearly show. In fact, Rome, like Britain, generally began her wars badly. By-and-by, muddling through by that stubborn determination of hers, she weeded out the incompetents and trained the likely men; and the legions, once they got a fair chance, turned the scale. But never in all her long wars of the Republic did Rome produce a captain to be named in the same breath with such a man as her great Carthaginian enemy Hannibal, until, at the very last gasp of the Republic, Julius Cæsar began to make war at an age when most men are thinking of laying aside the sword.

So if we want to know how Rome made herself mistress of the world, we have not to think so much of a few great captains with a heaven-sent genius for war, but rather of a great silent army, the most steadfast, the most enduring, the most adaptable tool of warfare that perhaps the world has ever seen, handled, on the whole, by merely average men, with here and there an unusually competent commander, and, not uncommonly, an unusually incompetent one. And in this chapter we want to take a peep at this great army which stood for all that was real and strong in Rome, which made Rome's Empire, and which saved it again and again.