People of the Deer (35 page)

There are approximately two million square miles of the arctic which are completely, or largely, suitable for reindeer raising. The caribou occupy much, but not all, of this area; but the preservation of these wild deer would not provide a serious obstacle to the introduction of reindeer.

The introduction of reindeer herding as an industry throughout the arctic would accomplish two things. First, it would assist the caribou and the sea mammals in providing northern men with the kind of food they require. Secondly, it would provide a sound economic basis for the inevitable transition which the northern people must undergoâor perish. The Eskimos (and many northern Indians) would be producing salable commodities. The world today is a meat-hungry world, and will remain one for as far ahead as we can see. In Alaska, reindeer meat is widely used by white men, and was even shipped south to Seattle, where it was distributed and sold as a luxury food until the pressure of the U.S. meat lobby forced the trade to be discontinued. The Eskimos of the Canadian arctic could do as well, or better, for they have access to a great ocean port (though one that is at present so little used as to be a serious financial embarrassment to us) at Churchill. From Churchill runs the shortest sea route to Europe, and in Europe animal protein is desperately needed. It might prove economically sound to establish a meat-packing plant at Churchill, not to prepare beluga for fox food, but to prepare reindeer and perhaps caribou meat, if the herds prosper, for shipment abroad. The plan seems reasonable, for at this moment we are canning horse meat in the central Canadian prairies, shipping it a thousand miles by rail, then transshipping it by lake and ocean freighter to Europe, where it is sold for human consumption at a good profit.

More than that, we could arrange to ship meat south from Churchill on the Hudson Bay Railway, which operates its southbound trains at heavy loss, and make the refrigerated meat available throughout Canada.

Perhaps it would provide a certain amount of competition with our cattle-raising industry, but I hardly think this would cause much annoyance to our general population.

The interior Barrens on the west coast of Hudson Bay could support a minimum of 200,000 reindeer, and the annual crop of meat from such a herd would be quite large enough to bring a full measure of economic independence to the entire present Eskimo population of the Central Arctic.

Before I leave this point of economic stability I must mention the fact that the need for this condition is apparently accepted in principle by the authorities who have throughout the years suggested such ideas as an eider-duck industry or white-fox fur ranching on the Barrens. These suggestions, and others, have been put forward over the last two decades, but no serious attempt has been made to implement any one of them. They have been purely and simply “cover schemes.” I cannot honestly guarantee that reindeer and caribou plans are certain of meeting all requirements. But they are a potentially effective method for achieving the results which the government has so frequently insisted it wishes to achieve.

With the establishment of a sound economy, the passageway from the world of the natives to our world would be open, and they could cross the void which now separates them from us, if they so desired. To date, we have tried only one method of bridging this gap, and that is to carry the northern peoples into our complex and unfamiliar life at one gigantic leap. Missionaries, for example, go to the arctic and suffer like martyrs so that in a year, or a decade, they can make professing Christians out of some heathen tribe. It is too great a leap. The so-called converts have no more idea of what lies behind the ideas they mouth than we have of what lies behind the eyes of God. Brave men, but dangerous men, the missionaries were also entrusted by the government with almost all the meager educational work being done in the North. In most of the church schools the Eskimos were taught the singing of hymns and the saying of prayers, but they learned little else and what they did learn was useless to them for it was not applicable to the physical realities of their present lives. Confused and baffled, they suffer for this attempt to “educate” them, since they learned only enough to make them feel vague dissatisfaction, without understanding how to bring about the changes which were needed. However, the missionary school system is advantageous to

us,

for it relieves the government of the need of spending tax money on the project, and it is beyond normal criticism, since few of us dare or wish to criticize the selfless efforts of the dedicated men who are our missionaries. Clearly what is required is to provide native teachers who have been rationally and intelligently trained and who can then go back to a healthy, unfettered people and teach what they have learned. The essence of the matter is to use no force. The northern natives should be in a position to embrace voluntarily and with understanding the white men's religious, economic and political creeds,

if they so desire.

Then the churches in the North could at least claim their new members were just that, and not the bemused dupes which native Christians now represent.

It seems to me that this is a sane point of view, but it is not shared by the Missions, for they have fought, and are fighting still, to keep the education of the northern natives in their own hands. It is a fight which is made more dangerous to the Eskimos by the violent competition between opposing religious groups, who often engage in most un-Christian strife, using the soulsâand bodiesâof the natives as their pawns in their strange battles.

Certainly the northern races can hope for little real opportunity to come to terms with our civilization until we extend to them the purely material facilities which are needed. Proper schools, proper medical facilities, preferably with native doctors, and a fair and honest economic treatmentâthese are the essentials.

To give a dying man a cup of water may be laudable; but to let that man die, when it is in our power to prevent it, is despicable. In effect we have been doling out cups of water to a dying people in the arctic, and have been free with self-praise of this benevolence. Surely we must possess a peculiarly facile turn of mind when we can virtuously condemn the cruelties perpetrated in other countries, while at the same time we avert our eyes from the cruelties we ourselves continue to condone in our own land. Certainly we are stupid and short-sighted, for the harm we do is not done alone to the Eskimos and Indians but it is done to ourselves as well.

20. The Days to Come

20. The Days to ComeThe ideas I have put forward in the preceding chapter are by no means the nebulous and rosy visions of an idealistic dreamer. For the most part they are originally not even my own ideas, but have been propounded by men who are more competent than I am to understand the dilemmas which face us in the arctic. And, fortunately, I have the proof that these ideas are not only realistic, but can be implemented readily enough if we sincerely wish to see them realized. I can tell you of a place where all I have asked for the natives of the arctic has already been granted to an Eskimo people. This place is Greenland, the far eastern outpost of the Innuit, where the Danish government has for many years followed an enlightened policy of native administration, a policy which pitilessly exposes

our

blundering efforts for the thin shams they are.

In Greenland today there are no people called Eskimos. There are only Greenlanders. Some carry pure Eskimo blood in their veins; some carry a mixture, and some are of pure Danish bloodâbut

all

are of one people. In that land there are men of Eskimo stock who teach in schoolrooms built for the children of all bloods. Native Greenlanders not only teach and are taught, but no limits are imposed upon their education. It is quite possible for a pure-blood Eskimo to pass through the Greenland school system, then go to Denmark (at government expense) to complete his education in a university. When such men return to Greenland they become the teachers of those who remain at home, and in this way the gap between the ancient past and our times is quickly bridged. And it is worthwhile at this point to explode the carefully perpetuated fallacy that if we tried to bring the Eskimos south to our schools, they would all contract our diseases and die. It does not happen in Denmark, nor has it happened in North America when the Eskimo travelers were healthy to begin with.

The descendants of men who speared seals on the ice packs of Baffin Bay now not only teach in schools but take an important, and increasing, part in industryânot as brute labor, but as men, of equal stature with all other men. They operate a large, efficient and lucrative fishing industry. They help operate the intricate scientific apparatus of weather stations. They assist in the operation of the trading posts, which are all government- owned and -operated, and which deal with the people at no greater profit than is required to maintain the service. In effect the Greenlanders now own their own economy, though it is supervised by Danish administrators and will be until the native people have reached the point where they can take over full control.

The Greenlanders are rigidly protected from the commercial exploitation which has a stranglehold on our arctic regions. The type of white men who know how easy it is to make a rich living from the heart's blood of a primitive race are forbidden to enter Greenland and they have no power there.

Natural food sources are protected with sane laws that are enforced, and it is seldom indeed that starvation comes even to the most remote areas inhabited by Greenland Eskimos. When a bad season, or other accident, brings hard times, the administration acts at once, and with full strength, nor does it wait to be shamed or frightened into taking action.

As in our part of the arctic, much of occupied Greenland is of a nature that is inimical to its habitation by Europeans. But the Greenlanders are a

part

of their land, for they possess the physical and mental heritages of the Eskimos, who long since learned how to live and prosper in that inhospitable region. Now, as a result, the Greenlanders are a race who can live in their own land and be happy there. They may well have something to contribute to the rest of the world in these sick times, and in the times which lie ahead.

And let me make this point clear: the Greenland natives are not serfs to white men's economic greed. They are not government wards, the voteless encumbrances of politicians. Instead they are a new people of increasing vigor, strength and understanding. Because one humane white race saw far into the future, the Eskimos of Greenland now belong to that futureâand the future belongs to them.

So you see, it can be done.

The Canadian artic is, today, a virgin wilderness with its chief resources still buried under ice and glacial rocks. The time is coming when this will no longer be true. The time is coming whenâas the Russians already have doneâwe will be living, working, and enriching ourselves in the sole frontier area which remains to us. It will not be casual exploitation of surface resources, as it is now. It will be a long-term development. When that time comes, and it cannot be far distant, consider the advantages to us of having a population-in-being throughout the bleak northlands. The Eskimos could be such a people. They could be most helpful partners, for they have the intelligence and ability and they alone can live and work in their bleak world without serious discomfort, and without needing the costly shields we should have to erect about white men in the same situation.

Freed of the incubus which we have laid upon them, the Eskimos could become as valuable citizens of this world as we ourselves are. The future of the Eskimos need no longer be limited to the barren rocks of their own land. The terrible days of the Ihalmiut could be put out of men's minds and in many places, even along the River of Men, new voices would be raised in living laughter where now only the voices of the forgotten ghosts are heard.

All this can happenâand if it comes to pass, it will be our gain.

As for Inoti, the one-year-old son of Ootekâshall it come to pass that in the winters which still stretch ahead, there may be no need for him to place

his

children under the dark snows because there is no food for them? Shall it come to pass that Inoti's mother may rest secure in the knowledge that she will never be called upon to walk into the midwinter night and not return, so that Inoti's children may live for a little longer under the cold dome of the igloo?

In the days of Inoti, the son, the strength of a great people might be made to live once more. In time it would be

our

strength, and the people would be

our

people.

And then the dark stain which is the color of blood might at last be wiped from the record of the Kablunait in the place of the River of Men.

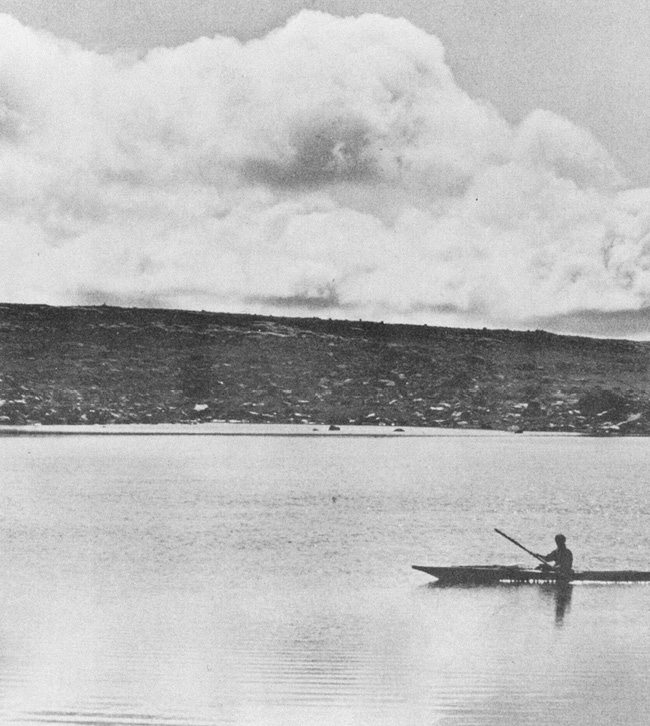

During the autumn caribou migration, the People of the Deer speared the animals at crossing places on many inland lakes such as this one in central Keewatin.

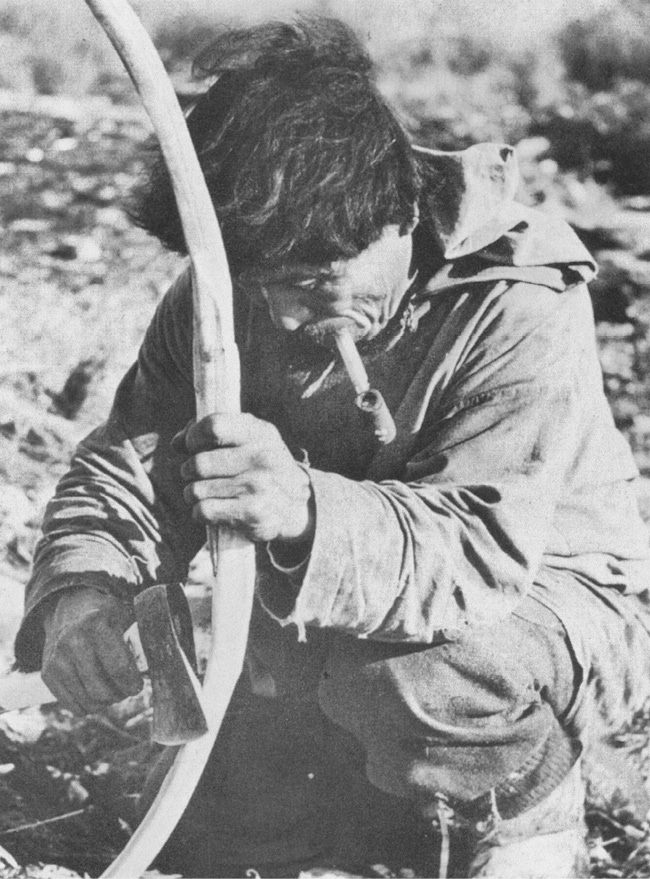

Pommela, the shaman, making a bow from sections of caribou antler at his summer camp in the Little Lakes country.

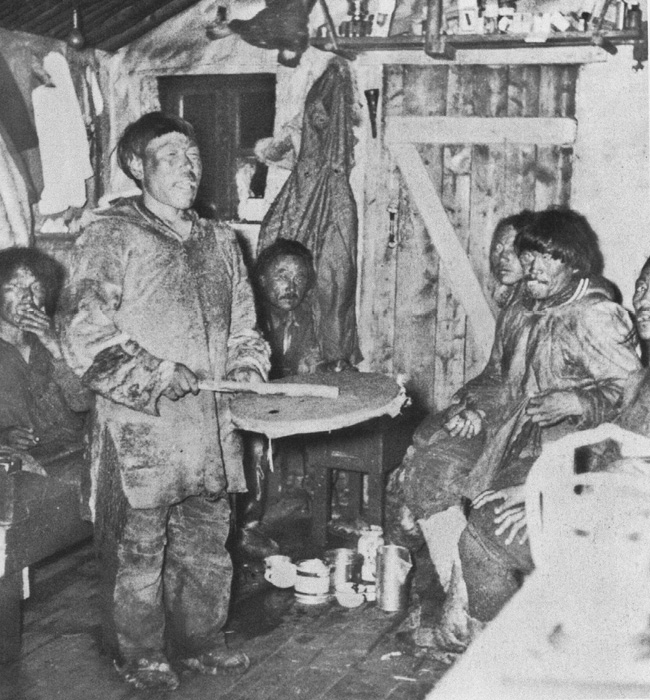

A social evening at Windy River cabin with a song-feast or drum dance in progress. Left to right are Miki, Ohoto (drumming), Owliktuk, Hekwaw and Ootek.

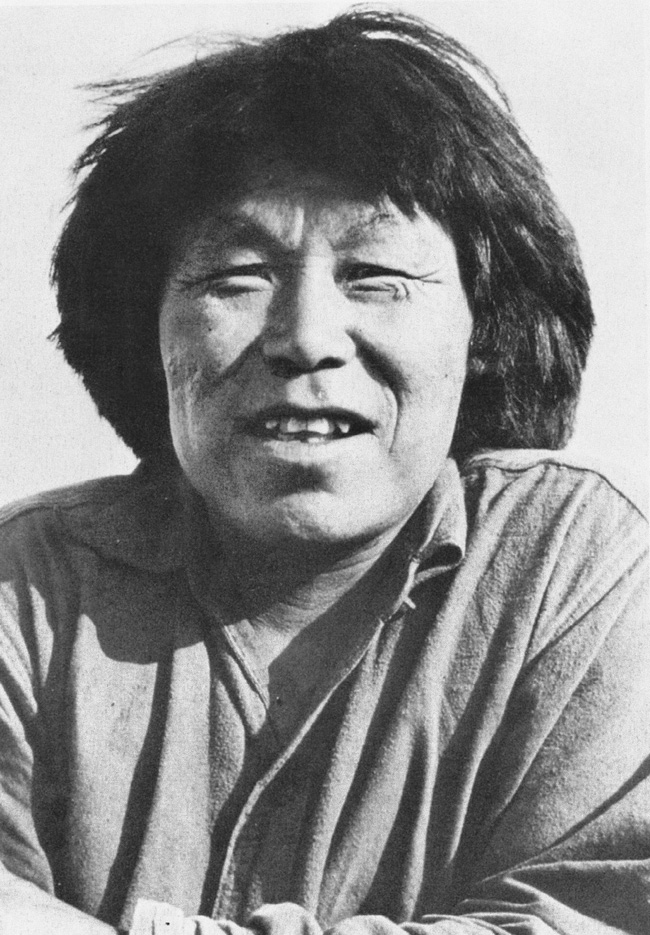

A portrait of Miki taken in the summer of 1947.

Ootek standing among the frost-riven rock of Ino countryâcountry of the Spirits.

Ootnuyuk, one of Pommela's wives, cleans a caribou skin at the author's travel camp in the Barrens.

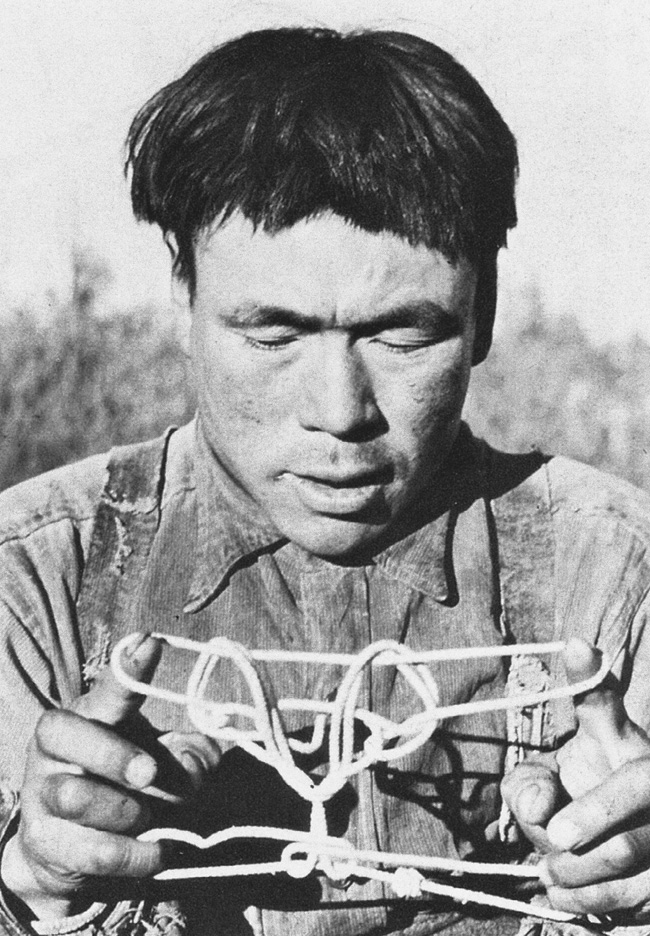

Ohoto making the string figure called TuktoriakâSpirit of the Deer.

Windy Cabin on the Windy River at Nueltin Lake with (left to right) Yaha, Owliktuk and Miki. The photo was taken just after they had been issued with cast-off army trousers.

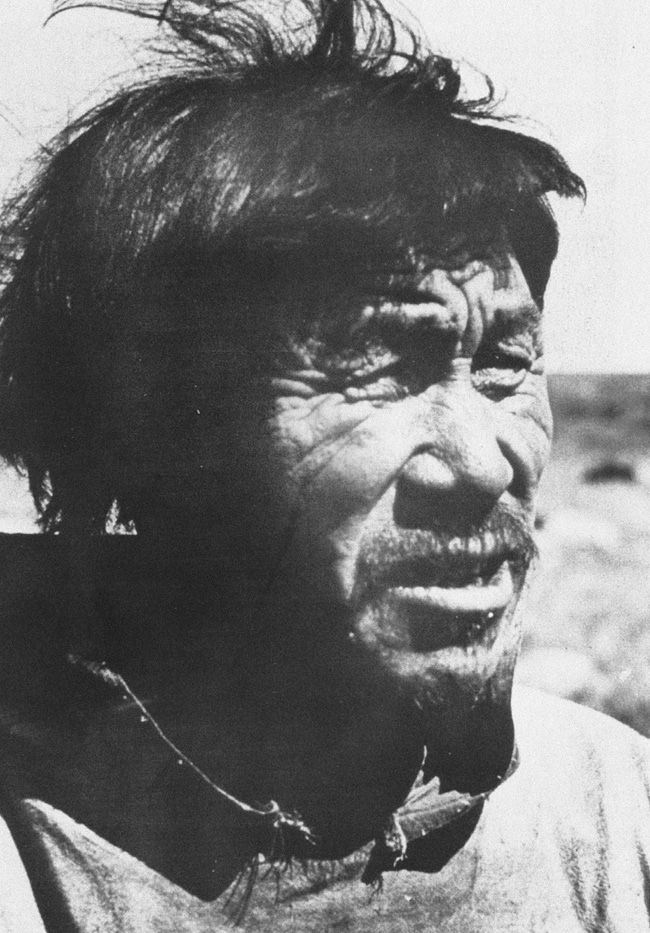

A portrait of Pommela, most powerful shaman of the Ihalmiut, taken in 1948.

An oasis of scrub spruce deep in the Keewatin tundra, not far from the Little Lakes. The skein of lines in the foreground is made up of caribou trails.

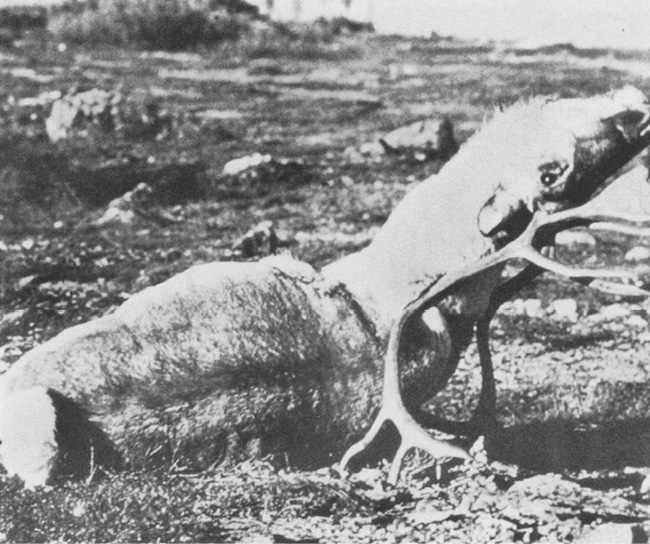

A fine buck caribou, killed in late autumn and cached for winter use. The upturned head resting on its own antlers will make it visible after the snows have fallen.

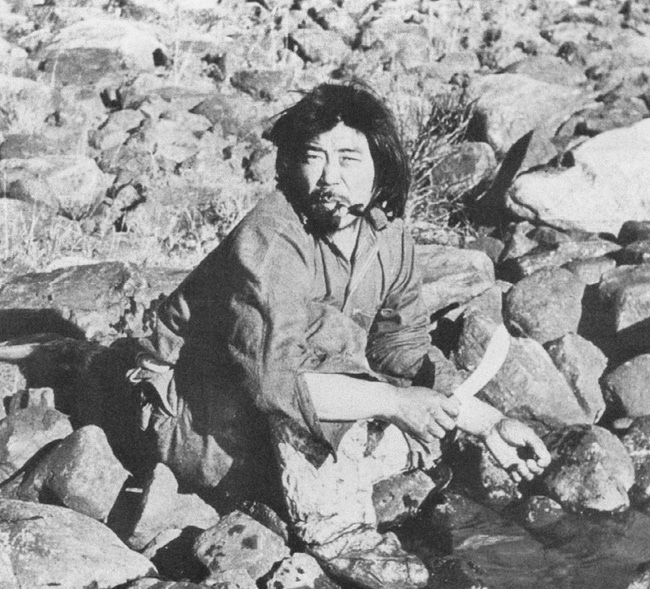

Yaha cleaning his knife after skinning and quartering a caribou on the banks of the Kazan River.

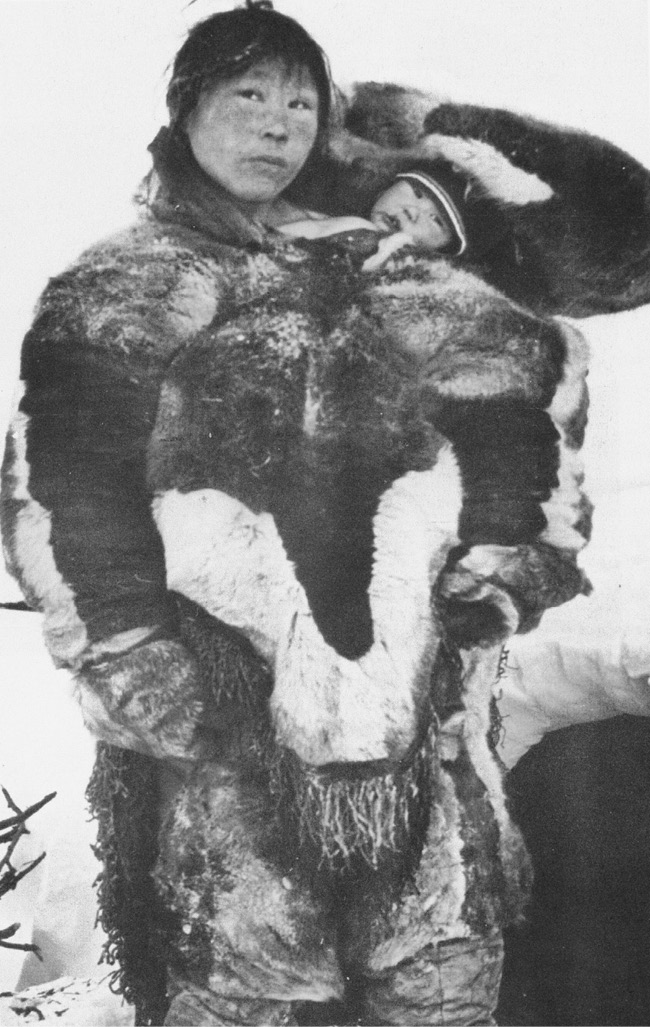

A young Padlei woman carrying her child in the amaut, standing outside a travel snow house. She is in full winter dress.