PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk (22 page)

Read PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk Online

Authors: Sam Sutherland

“I went into Star Records, and I was basically undercover because no one knew I had been told to go in and take over the store,” Bryden says. “And it was just insane. It was crazy. It was wacky. All the punks were behind the counter. There was no sense of order or any business-like approach to anything. You walked in the store, and it was just chaos. It sounds fun and cool, but my job was to restore order. Which I did.” Kobak had been using the store as an informal bank to fund Teenage Head, who he was managing. Money from the Star Records till went to everything from Teenage Head equipment to practice space rent; on one particularly busy Saturday, it’s been said that Kobak simply handed Head guitarist Gord Lewis enough cash to buy a brand new Les Paul. Bryden was the killjoy who had to stop the party, and it made him pretty unpopular for a brief period of time.

“I tried to do it creatively,” he says. “I didn’t want to go in like a bureaucratic suit. But the business was dying. If someone didn’t do something, Star Records wouldn’t have lasted another six months.” Eventually, the city’s punk populace forgave him. And while Teenage Head’s reign at Star Records came to an end, the Forgotten Rebels’ was just beginning. “In the long term, what Star Records did was get Teenage Head going,” Bryden says. “Teenage Head had their day at Star. They practised there, they got their equipment. It was time for the Rebels to step up.” With the eventual release of Bryden’s version of

Tomorrow Belongs to Us

, they did.

Leaps and bounds ahead of the band’s first attempts in the studio, the record took the best elements of their demo and presented them in a tidy package: the catchy choruses, DeSadist’s unique vocal style, and, most memorably, his vicious sense of humour and worldview. While there was plenty on the record designed to draw the ire of sensitive folks, the band faced the greatest criticism for the Nazi imagery of “Reich ’N’ Roll,” and “3rd Homosexual Murder,” a song about a rash of murders happening in gay clubs in Toronto, written from the perspective of the killer. The band was labelled anti-Semitic and homophobic, despite the fact that one song was barely veiled parody, the other a ripped-from-the-headlines account with no sympathy for the narrator. It didn’t matter; the band was boycotted by local alternative media and radio, including the only punk-friendly radio station in Ontario, CFNY. It took all of Bryden’s charm and contacts in the industry to get the band a coveted slot opening for the Ramones at a CFNY-promoted show in the nearby suburb of Burlington.

“There was a lot of politics and back and forth about what they could play,” says Bryden. “Finally, they were allowed to play, but they weren’t supposed to play ‘Reich ’N’ Roll.’ That was the deal. It was in writing. So of course, three songs into their set in front of 3,000 kids, Mickey goes, ‘I know we’re not supposed to play this song, but we’re going to anyway. One, two, three, four!’ And suddenly you have all these kids singing, ‘I wanna be a Nazi.’ I did not anticipate what was going to happen, though.” A few days later, Bryden was at work at Star when he got a call from the Halton Regional Police. A formal complaint had been lodged, and the Attorney General was now investigating the band to determine if they were a neo-Nazi organization.

“I literally said to these detectives, ‘I assure you, the Forgotten Rebels are not a neo-Nazi organization bent on overthrowing the Canadian government. They’re just kids, trying to shock people,’” Bryden says. “‘And guess what? It worked. You’re shocked.’” The charges against the band were eventually dropped, but the repercussions continued, with radio and media refusing to cover the Rebels as a result. They went from getting press for their outrageousness to being ignored for it, which made capitalizing on their local popularity difficult. Despite the trouble it caused the band, Bryden offers up the most succinct defence of the band’s dark approach to musical comedy. “The devil hates humour,” he says. “Hitler hated humour. That’s the only weapon we have against tyranny.”

The heat proved too much for the rest of the band; DeSadist was faced with having to build the Forgotten Rebels from the ground up once again when everyone quit on him, for the third time in just over a year. But he would soon find more than an able, beer-thirsty, and otherwise disinterested rhythm section; new recruit Chris Houston would prove to be every bit as weird and funny as DeSadist, as adept at writing a catchy melody, and, importantly, as capable of handling the reactions that came with being a Rebel.

“I’d hang out with him at Tim Hortons and just let him talk,” says Houston, who is sitting in his office in a downtown Hamilton music school. A lifetime musician, Houston is one of the kindest and most enthusiastic people I’ve spoken to during this entire period. His genuine affection for the Rebels, a band he was only in for a short period of time, is apparent in his lengthy, thoughtful answers. And his passion for the city is unmistakable — after our conversation, he insists on taking me to his favourite Italian restaurant, tucked away in a basement on James Street, before guiding me around the city and pointing out all the long-gone sites of important local punk history: Star Records, the Saucer House, the house where he and DeSadist first recorded demos for the second Forgotten Rebels LP. It makes sense that he spent days just talking to DeSadist, developing an understanding of his motivations and his goals, before joining the band officially. Chris Houston is smart and thoughtful, and it’s doubtful he commits to anything without being fully invested. “I guess I just convinced him to let me join the band,” he laughs.

A guitarist by trade, Houston’s first home in the Rebels was behind the kit, before he eventually moved to bass. His first show happened at the Turning Point in Toronto, and proved to be par for the course with early Rebels gigs. Whether or not Houston was ready was another thing. “I saw one person have their teeth smashed out on the table; someone had their ribcage smashed; there were four broken arms and three broken legs,” he says. “This is while I’m playing onstage, my first time with the Rebels playing drums, and you’re looking at, literally, mayhem. That was just horrible. It makes a good story now, but for those people . . . Jesus Christ.”

“It was gang related,” explains DeSadist. “The gangs hung out together, beat the shit out of each other, and then would go drinking together. Rival gangs that weren’t that rival until they got drunk, you know? That whole crowd, they hung out together after. They drove each other to the hospital.” It was an appropriate beginning to Houston’s time in the band, and the new Rebels quickly circled their wagons to begin work on a new batch of songs. With two equally twisted and creative songwriters in the band, the Forgotten Rebels looked to push good taste even further than they had in the past, drawing once again on the

theatrics of classic wrestling and the natural absurdity of the

news of the day. Songs like “Bomb the Boats and Feed the Fish” played on the violent xenophobia of older generations, rallying against immigrants coming to Canada to steal jobs (and suggesting that we “bomb the boats and feed their fucking flesh to the fish”). “Elvis Is Dead” attacked rock and roll’s greatest sacred cow with a rollickingly rockabilly beat, DeSadist’s best Elvis impression, and lyrics about stealing the King’s body from his grave. And “Fuck Me Dead” extolled the virtues of necrophilia with such subtle poetry as “A pillow and a coffin’s just as nice a bed / Baby I love it when you fuck me dead.”

“Between Mickey and me, we’d always be trying to out-gross each other,” Houston says. “Mickey would always show up with really great songs, and we’d work on them together. I’d always be on the floor laughing. He’s a bit of an exhibitionist when it comes to saying things; we just tried to write the most disgusting songs we could possibly think of.” Enlisting Bob Bryden once again, the band set about recording

In Love with the System

, their second full-length record, in 1980.

“We instituted what I call ‘Commando Raid Recording Techniques,’” Bryden says. “We did everything really fast.” Much of the record consists of live-off-the-floor first takes, and Houston credits the prep work done by Bryden for their crispness. Despite the speed with which the band had to run in and out of the studio, the result was even better than its predecessor. Containing some of the same songs as their demo and

Tomorrow

, the Rebels had finally figured out how to behave in the studio, deferring to Bryden to add a few sonic bells and whistles to keep things interesting. The record is light years ahead of the output of many of their peers from the same period, owing to Bryden’s studio creativity and the stellar songwriting of Houston and DeSadist.

“It was just well-crafted,” says Bryden. “There’s a tremendous musical and lyrical ability on those first two records that is far superior to 99% of what was happening in punk all over the world. Mickey wasn’t afraid to write great songs. I felt like he was closer to the Clash.” Bryden has a point, although it’s a leap to imagine “Lost in the Supermarket” being about fucking a corpse. But ultimately, it was that tension between the craft and the subject that made the Rebels’ material so compelling; if they had written about love or the looming threat of nuclear war, who knows where things would have ended up. But they wanted to write about Elvis.

Despite the work that had gone into crafting

In Love with the System

, the Rebels still weren’t connecting with a big enough audience. The band was never embraced in Toronto the way Teenage Head was; DeSadist would always hold a sarcastic grudge about being snubbed by the Last Pogo — in the documentary film of the same name, DeSadist appears, giggling and clutching a Rebels LP, to declare, “The Last Pogo was one big fart. That’s ’cause we never played. They can’t take a real punk band here.” It would take years (and the invention of the internet) for them to really find a niche and grow into one of Canada’s most legendary punk bands. But in 1980, they were still an unpopular bunch of guys forced to travel by Greyhound between shows.

“We were so desperate that we would actually load all our gear on the bus,” says Houston. “The secret of touring by bus is you put all the drum hardware in a golf bag or a hockey bag and they think you’re hockey players. They don’t want to see guitar amps, so you have to hide it in sports gear. They think you’re a sports team.”

In the end, there were a few factors that led Houston to leave the band, marking the end of the first truly great era of the Forgotten Rebels. The first is pretty simple: “You can’t have two Hitlers in one band,” laughs Houston. “I’m a control freak, and so is Mickey.” The second was touring — the band didn’t.

“Paul Kobak had lined up a tour, but Mickey didn’t want to do it because he wanted to stay close to work,” says Houston.

“I got hired by an elevator manufacturing company, and I was making grown-up wages,” says DeSadist. “We thought we were going to be rich as fucking hell because we were so far ahead of everything. We were nastier sounding than the Sex Pistols on record, and we thought we were going to make a fortune. Think of how few gigs the Sex Pistols played. Think of how few gigs the Beatles played. They probably played less gigs than the Rebels did.”

Ultimately, songs like “I Left My Heart in Iran” just couldn’t compare to “I Wanna Hold Your Hand,” and the band split for the umpteenth time. DeSadist’s follow-up was

This Ain’t Hollywood

, which still contained a handful of songs co-written with Houston, including the classic “Surfin’ on Heroin,” a simplistic ode to exactly the activities implied by the title. The song has become one of the most infamous of Canada’s generation-spanning punk oeuvre. The Rebels eventually ended up touring, helping them become one of the most popular punk bands in the country. Still, it’s hard to compete with the raw power and unfiltered craziness of DeSadist and Houston’s vision.

“Those records are so raw and so much fun,” says Bryden. “You might have to turn them up louder than a normal record, because we didn’t know much about mastering.” He laughs. “But they’re so much fun.”

I’m back at the sign for This Ain’t Hollywood in Hamilton, watching happy drunks young and old stumble out into the night. There’s something reassuring about knowing that, even when the records are all out of print and the band has long stopped playing, there will be something lasting in this town to remind everyone that something really great happened here. Because it was fun, it was original, and it was local. That’s the most important thing. The Hammer made its own Hollywood in the shadow of Toronto, one double double and sarcastic ode to Nazis at a time.

VICTORIA

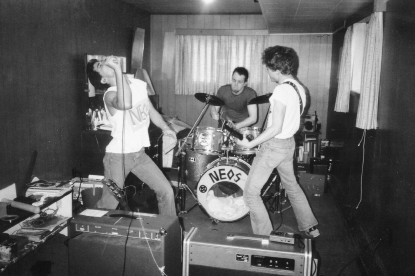

The Neos [© Pete Ells]

November 16, 1979, 4:30 p.m. PST

Pink Steel is performing at the Spectrum Community School variety show, and they’re out of tune. Horribly out of tune. Their sound is shambolic and embarrassing. It’s so bad that other students look at each other and realize that there is no reason they can’t start a band. Within a few weeks, Victoria goes from having one punk band — the out-of-tune, unrehearsed Pink Steel — to several, including those unimpressed variety show attendees, who now go by the moniker the Infamous Scientists. The I-Sci’s would help seed some of the city’s best and brightest punk outfits, including Nomeansno, an internationally respected three-headed beast still touring three decades later. But right now, Pink Steel just an eight-piece mess, rambling their way through “Sat on a Slug,” a song about the perils of smoking pot near railway tracks, and the kids are just thinking, “Even I can do that.”

There was once a thriving underground city in Victoria. Not just below the radar, but, quite literally, below the streets. The bucolic capital city of British Columbia, Victoria is like Canada’s upper middle class impersonation of Florida; popular with retirees, it’s a city that lacks much of its own youth culture, at least superficially. Known as the City of Gardens and located on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, roughly 90 minutes by ferry from the mainland, Victoria is one of the sunniest cities in Canada. And it’s really warm, pretty much all the time. Why everyone in Canada hasn’t moved there escapes me as I write this paragraph.

In many ways, the explosion of punk and hardcore in Victoria mimics the social conditions present in the early Southern California scene. Kids here couldn’t relate to the bleak urban image of bands from New York and London, even if they loved their music. But a heroin addiction isn’t a prerequisite for feeling out of place inside dominant culture, and disaffected youth, whether they were getting beat up by surfers in Huntington Beach or beat up by gardeners in Victoria, were able to seek solace in the promise of punk. And metaphorically, it’s hard to ignore that Victorian underground. In a city as perfect as the City of Gardens, a maze of tunnels under its sidewalks and streets functions as a constant reminder that superficial impressions are rarely complete. And, more importantly, that Victoria is hiding some dark shit.

Tunnels, long collapsed, weave their way under the city. Once used to transport Chinese slaves brought into the country to help build the railroad — a gross humanitarian injustice that the Canadian government formally apologized for in 2006 — they later found use as connecting passages between gambling parlours and opium dens, doubling as secret escape routes from police raids. Later, the tunnels helped

bring goods from the shipping yards to more respectable

businesses growing in the downtown core. The tunnels have

since collapsed, but a handful of spaces that run under the sidewalks in Victoria remain. Ceilinged by prismatic purple tiles, these huge underground areas, supported by wooden beams and cast in a pale purple light by the translucent tiles above, still remain hidden in plain view along the streets of downtown Victoria. It doesn’t matter if it’s punk or gambling

or evening wear; the underground might change, collapse, or

disappear completely from view. Even in a place as pristine

as Victoria, British Columbia, it is always there.

The punk scene here sprung from a cancelled drama class. A subtle beginning, but we’ve all got to start somewhere. “We were high school drama students,” says Jeff Carter, keyboardist for the first punk band on Vancouver Island, Pink Steel. “It was the spring of 1978. We had a high school play on the go, and we had an evening rehearsal scheduled that was cancelled as we arrived. So five of us ended up smoking a little pot and launching into a long, stoned improvisation where we basically invented this band and came up with a whole story, a song, and everything.” The band was Pink Steel, and the song, detailing a friend’s unfortunate contact with a slug, was titled “Sat on a Slug.” While the band spent six months as little more than a stoner drama student joke, by October, Carter and vocalist Peter Campbell decided it was time to turn Pink Steel into a living, breathing rock and roll band. Says Campbell of the long-simmering decision, “We just followed through on that implicit threat.”

Depending on your point of view, Pink Steel is either the very essence of punk, or a prolonged drama exercise. The band themselves make no claims to any righteous motivation or greater punk plan. “When we formed, we were calling ourselves a punk rock band, but all we knew about punk rock was reading the occasional newspaper story about the Sex Pistols,” says Carter. “I didn’t own a Clash album until January 1979. I mostly listened to Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones.” Influences aside, Pink Steel still formed under the same conditions as other explicitly punk bands of their era, and their initial influence locally was immeasurable.

“There was no scene in Victoria at that point,” says Carter. “As far as we knew, we were a completely isolated phenomenon. We played house parties, because that was all you could do.” Slowly, Pink Steel began to take notice of other bands like them, as punks gently bubbled to the surface in Victoria. They were musicians with no hope of playing a local bar, but with an enthusiasm for doing something different in a culturally conservative city. Pink Steel first met the Sickfucks, a precursor to the infamous Dayglo Abortions, while practising in a second-floor apartment; the band’s drummer yelled at them from the street.

“After that, I saw the Infamous Scientists for the first time,” says Carter. “That’s when I knew a little scene was about to start.”

When John Wright and Tom Holliston, drummer and guitarist from the legendary Victoria band Nomeansno, pause outside of the bar I’m holed up in, I’m seized by panic and immediately begin to sweat. The band’s publicist, a mutual friend, has arranged for us to meet, but I was not planning on staging our introduction here. I’m across the street from the venue where they’re performing later tonight, tucked inside a loud zebra-print booth in a vulgar martini bar, one that doesn’t scream out “Tell me your secrets, because I am a legitimate punk journalist.” While the wood-fired pizza oven (and, if we’re being honest, the half-price martinis) justifies my presence here internally, I’m not sure how this looks from the outside and I’m not in the habit of conducting interviews from a castaway

Sex and the City

set. I clam up at the thought of one of my favourite bands thinking that this is the kind of bar I hang out at. Even though I obviously hang out here.

Unfortunately, this is exactly where I meet John Wright and Tom Holliston. Mercifully, they agree that the pizza is delicious.

Both Wright and Holliston have been pillars of the Victoria scene since its inception. Wright played drums and keyboards with Infamous Scientists, and Holliston fronted Pat Bay and the Malahats, later becoming the manager of Club Hacienda in the mid-’80s and thus helping to keep the scene in the city alive by giving alternative bands a place to play. He joined Nomeansno in the ’90s.

The Victoria scene flourished from 1981 to 1982. Which isn’t to say incredible contributions weren’t made after; some of the best punk bands to emerge from the city, like Nomeansno and Red Tide, didn’t produce their seminal works until the mid to late ’80s. But the creative explosion that started with Pink Steel expanded to unforeseeable proportions within a few years, producing an incredible number of bands out of a few small high schools and a few neighbourhood skaters.

“I lived in Edmonton for a while, and I feel like the two cities were really similar,” says Holliston. “You didn’t meet people who were aspiring to be major label artists. It was like trying to get to second base in heavy petting matters. You just wanted a show, or to be able to buy a guitar. There was no grand scheme, and things would just fall into place, or they wouldn’t.”

Bands sprung up, played a show, dissolved, and reformed in some new configuration. But unlike other cities where this kind of cycle was the norm, the Victoria bands almost all recorded. Even if it wasn’t in a studio for a proper vinyl release, they would find a way to preserve their original songs before moving on to the next short-lived project. The city also possessed a valuable tool that helped set it apart from other first-wave scenes: Rob Wright.

“My brother got into the Ramones right away,” says John Wright, who founded Nomeansno with his brother Rob in 1979. “I was still in junior high school at the time, playing in the jazz band, and listening to whatever popular rock was out there. I wasn’t really into rock all that much at all. He had been playing guitar for a while on his own, listening to jazz and blues-rock, but had become pretty disenchanted. But these original punk bands were inspiring to him. He got a TEAC 4-track, which, at the time, was a pretty high-tech piece of gear for a home recording studio. Me and him just started playing around and recording.” The Wrights’ basement would become ground zero for many of the recordings to emerge from the city during the late ’70s and early ’80s. In a country full of woefully under-documented bands, Victoria is an exception, an advantage exemplified by the unbelievably complete

All Your Ears Can Hear

project.

Undertaken by a handful of area archivists led by Jason Flower,

All Your Ears Can Hear

compiles biographies, discographies, and photos of every single punk band in Victoria from 1978 to 1984, accompanied by two CDs featuring recordings from each band in the book. It’s a remarkable anthropological feat, one that speaks to the greatness of the era documented as much as the passion of those documenting it. There was no shortage of wonderful, strange music being made in Victoria during the time period covered by

All Your Ears Can Hear

, and the very existence of such a fantastically complete work tells you all (or, a lot of what) you need to know about the value of Victorian punk and hardcore.

Amongst the bands who recorded with the Wrights were the Neos, regarded by many as the best of the early scene. A proto-thrash band, the Neos were obsessed with speed before it became standard practice, much like Winnipeg speed freaks the Nostrils, who also amped their tempos up to inhuman levels long before the popular reign of thrash and speed metal. Formed in 1979, their express intent was to be the world’s fastest band, which, for them, simply meant playing faster than

Never Mind the Bollocks

. Future bassist Kev Smith saw Neos’ first show, a night he still remembers vividly.

“There was a particular excited vibe that night — I think most of us knew this was the beginning of something great, where the local punk scene really coalesced for the first time,” he says. The band took the stage of the Ray Ellis Dance Studio, rented through “subterfuge,” in front of about 150 people. “I’ve never seen another performance quite like it. It was like they had a very definite idea about what they wanted to do, but were so raw and amateurish that it was hard to figure out what was going on. It wasn’t even clear who was in the band at times. The sound was powerful but so chaotic that the whole thing came across as a really exciting but virtually unintelligible explosion.”

Smith recognized that he and the band shared similar ideas about music, and before long, he had joined as their full-time bass player. The Neos only got better from there, and it wasn’t just locals that noticed; after sending their demo to Jello Biafra, iconic frontman for Californian hardcore forefathers Dead Kennedys and owner of Alternative Tentacles Records, the Neos were asked to come and open for the band on an American tour. They couldn’t. They were 15 years old, and their parents wouldn’t let them. Years later, the Neos would still retain their international profile, regularly covered by bands like Charles Bronson and NOFX.

“The Neos were one of the fastest bands out there. It sounded out of this world,” says Steve McBean. Best known today for his Polaris Music Prize–nominated sludgy rock outfit Black Mountain, McBean was even younger than the Neos when he formed his first hardcore band in Victoria, Jerk Ward. “The Neos were our blueprint. That was

the

band. All of a sudden, it made sense. The Ramones and the Clash were larger than life. The Neos were like us.”

Rumours about their early practice habits and methods of delivering their signature speed-crazed punk abound; my favourite comes courtesy of one of my pizza partners, Tom Holliston, who met the band after they threw a hammer at him on the street. The reason, apparently, was that they liked Holliston’s clothes.

“When they would practice, they would put as many sweaters on as they could, turn the heat up as high as they could in the house they were practising in, run up and down the stairs, play their set as fast they could, and then collapse in exhaustion,” he tells me. When I ask Smith to verify the story, he calls it “substantially true.”

“We were obsessed with them,” concludes McBean.

The Infamous Scientists began to build their reputations for left-field tunes and wild live performances around the same time as the Neos and Nomeansno. John Wright would eventually join the I-Sci’s, performing with them while simultaneously working on Nomeansno recordings with his brother in the family basement. In addition, Andy Kerr, the I-Sci’s guitars and vocalist, would himself join Nomeansno as the band’s first guitar player a few years later, but for a time, the Infamous Scientists existed on their own solitary island of punk weirdness. The band’s recordings are interesting, but when viewed alongside the numerous live clips floating around online, you can really get an idea of the grounded experimentation that was the Infamous Scientists’ stock and trade. They weren’t as aggressively bizarre as Nomeansno, nor as straight-ahead aggressive as the Neos. They were quintessentially Victorian, a classically rooted punk band that would have sounded like Martians in any other city.

“In Victoria, there was no concept other than what you did,” says John Wright. “It didn’t dawn on anybody to take on a particular image. Sure, people would put safety pins on their jean jackets, but it was more of a homegrown thing. Everyone knew each other. The idea was just to do something different — and do what you want.” While Wright was helping Kerr and co. do what they wanted in Infamous Scientists, he and his brother continued to build their own project, culling together the nine songs that would comprise their full-length debut as Nomeansno, 1982’s

Mama

. Recorded on Rob’s TEAC 4-track, it was the first step in a storied career that has lasted until the present day.

Mama

is just the rough first hint of where the brothers would later take their progressive punk sound, eventually leading to 1989’s watershed

Wrong

, a gold-certified slice of hardcore, funk, metal, and whatever other weirdness passes between the ears of the Wright brothers on a day-to-day basis.