PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk (26 page)

Read PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk Online

Authors: Sam Sutherland

But life wasn’t all attempted hangings and wintery

Dukes of Hazzard

escapades in Saskatoon. Bolstered by the audience for new types of music that Ron Spizziri had been nurturing through his store, radio show, and a new cable-access TV show (what wasn’t this guy doing?), a group called the Alternative Music Society formed at the University of Saskatchewan, hell-bent on bringing some real punk shows to the prairie outpost. The AMS succeeded in helping to build a viable scene within the city, bringing bands like Simple Minds and Social Distortion to town and giving new bands an opportunity to get their sea legs opening for established acts.

“It was a social outlet,” explains Darlene Froberg, a former member of the AMS. “But it was its own little subculture, too, because at the time, Saskatoon was a small, conservative town. We got hassled a lot because we had green hair and looked like punks.”

“They were a cool group of people, and they liked us,” continues Semko. “They liked the fact that we were different, that we played original music. So we got a lot of gigs, good opening slots for people that they brought in, like the Cramps.” Bringing American psychobilly bands to Saskatoon wasn’t Darlene Froberg’s only extracurricular activity; along with her sister, she operated the city’s lone punk clothing store on Broadway, a tiny second-floor enclave called Propaganda, Saskatoon’s own Let It Rock, with a tiny northern colony standing in for the sprawling metropolis of one of the world’s oldest and largest cities.

“We had bondage pants and army coats, ruffled shirts from the ’60s,” says Froberg. “We had that little market cornered because the people that were going to the shows needed something to wear. We’d buy clothes from all over and sell them second-hand. We were only open about a year. It wasn’t very lucrative because our market was so small, but it was a lot of fun. People really enjoyed it.”

Other bands began to pop up at that time, including Doris Daye and, later, Seventeen Envelope, which featured bassist John Sinclair and Semko’s future Northern Pikes bandmate Bryan Potvin. Sinclair eventually moved to Toronto, joining Edmonton native Moe Berg in the Pursuit of Happiness, recording with Todd Rundgren and opening for Guns N’ Roses. Not a bad future for a couple of prairie punks.

“I was 18 years old,” recalls Potvin. “I was working a part-time job. I was in the last year of high school. And I got this cold-call from this guy named Johnny Sinclair saying, ‘Hey, you play guitar. You want to jam sometime?’ I was like, ‘Sure.’ So I went over to his house and he had this massive collection of records by artists I’d never heard of. I was like, ‘What the fuck is this?’ This whole world of music I had no idea existed. Within a week of knowing John, I went into this used record store in Saskatoon with three milk crates full of my records, all my Led Zeppelin and my YES. I just dropped them and said, ‘Take it all. I want to swap out.’”

While Doris Daye never played outside of Saskatoon, the band, like others, provided a valuable outlet for alienated kids living in a culturally conservative climate, helping to build a foundation for later musical successes.

“I wouldn’t say we were originators of anything,” says John Sinclair. “But we found a way to express ourselves within that, you know? That was a comfortable place for us to come out as artists and musicians.”

“We looked like a bunch of fucking weirdos,” laughs Potvin. “We were eclectic looking. And almost impossible to book.” Like Sinclair, Potvin sees the value in the band as much greater than the roughly 10 shows they played together. “I think if punk taught me anything about art, not so much about business — it’s just honesty. I think that’s really what it boils down to. That’s what I learnt from those late teen years when I was focusing on that type of expression. It’s just honest. I think that audiences eventually smell a rat when someone’s not being honest with that. That’s what it comes down to.”

Although the burgeoning scene was flush with enthusiastic, motivated music fans like Potvin and Sinclair, there were some very real dangers underneath the surface. Bar fights and threatening audiences could spark genuine violence directed at bands like the Idols. Scarier still is the unsolved murder of a young punk, rumoured to have been targeted for his appearance. Details are scarce and memories have faded over 30 years, but Froberg specifically remembers being questioned by the police.

“The police came, they interviewed my sister and me at the store, along with all our friends. That was quite bizarre. They weren’t questioning us like we did it. They were questioning us like we might know who did it,” she specifies. “I didn’t really know him, he just kind of hung out with us. He was down on Spadina Crescent, by the river. It was late at night, like one in the morning, and he’s walking and somebody pulls up because he was dressed weird, and he was beaten to death. It shook everyone up. It was like, ‘Do we have to stop what we’re doing and being who we are? Is this a threat to us as individuals because of how we look and what we’re doing? Or is it something that the guy did by himself that brought it on? Or was he just in the wrong place at the wrong time?’ For a while after that, people wouldn’t really want to go out alone.”

When the dangers weren’t coming out of pickup trucks in the middle of the night, they were exploding at the shows themselves.

“I remember the first two weeks in December 1980. It was brutally cold, I’m talking –40 Celsius,” says Jay Semko, detailing a particularly surreal Idols set. “We had a two-week gig at a hotel. You had to play four sets a night, and it was a big deal to us because we’re an oddball band, and to actually get a full two-week booking was great. But you had to sign this thing where you couldn’t drink while you’re playing. At the very end of the night, I had a five minute window where I could order myself a beer. So I order a beer, go sit down at the table, and this brawl breaks out. And there’s only, like, 30 people in the bar, it was so cold. It was like an Old West barroom brawl, ‘Everybody partner up and fight!’ People breaking beer bottles and trying to cut each other. I’m sitting in the middle of all this, and I felt like I was invisible. I didn’t want to move because I thought somebody would attack me. The soundman was covering the mixing console with his body. I was able to weasel my way out of there and into the lobby. The guys were all watching TV and said, ‘John Lennon got shot.’ And I was like, ‘What?’ And then the fight spilled out into the lobby and this one guy got thrown through a window. He came back the next day to work the bouncer. And his whole back, it looked like he was bitten by a shark.”

By the early part of the 1980s, things were transitioning in Saskatoon. New bands continued to form, while the first-wave bands were breaking up and reforming in new configurations, the most notable being Potvin, Semko, and the Northern Pikes.

“There were a lot of bands that just came and went back then,” says Spizziri. “You’d see them open for a touring band once or twice, and they’d disappear. I guess it’s just so hard because we are so isolated out here, especially back then. Most of them felt they had to move away from Saskatoon. The Northern Pikes were the first band that were proud to be from Saskatoon. I’d be visiting Toronto and catch them at the Diamond Club or the Horseshoe, one of the nice venues. And they’d be announcing, ‘We’re from Saskatoon.’ They weren’t hiding it.” It should come as no surprise that Spizziri’s son now plays in a band that tours internationally and proudly calls Saskatchewan home; buzzed-about indie kids Rah Rah, who had a show in Paris, France (not Ontario), on the night Spizziri and I spoke.

“We had a lot of fun, we really did,” concludes Semko.

“We had a blast playing. I guess I enjoyed the abusive times.

I really got a kick out of those gigs when we weren’t as well liked as we wished we were. To me, in some ways, we were

accomplishing our goals, as odd as that sounds. And once we did our thing with the Idols, there were tons of other groups doing similar things. So I can’t help but think we had an influence in people moving forward a little bit in music.”

OTTAWA

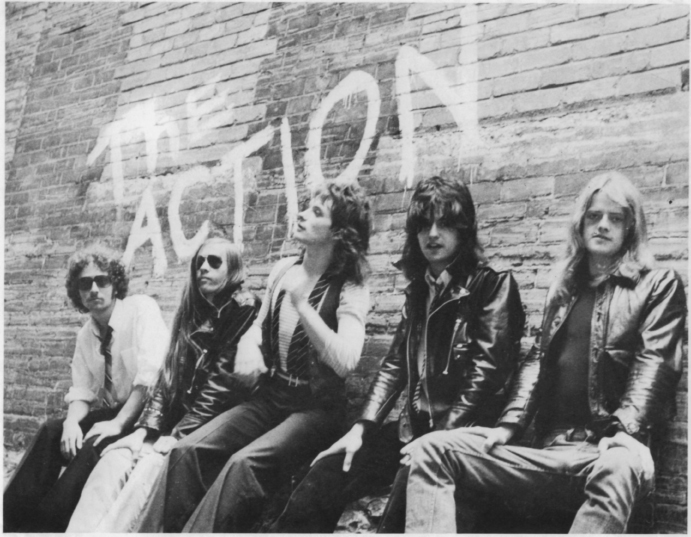

The Action [courtesy of Ted Axe]

December 31, 1979, 11:59 p.m. EST

In a tiny basement below a shawarma joint, 200 kids are crammed into a room fire coded for about 75. Ritalin, still a new, unknown psychiatric drug, is passed around the bar, while two people are literally fucking against a wall to the right of the stage. The Bureaucrats are performing, ready to ring in the new year, celebrating the first six months of a centralized Ottawa punk scene. It’s all been built around this bar, the only one in the city with a strict no-covers policy. The Rotters Club has become the official headquarters for Ottawa punk, and this evening of late-night revelry is a celebration of all the things that have changed since it planted its foot on Bank Street. The calendar rolls over to 1980, and the party rages until 5 a.m. Despite the arrival of a pair of ambulances to whisk two audience members, felled by alcohol poisoning, to the hospital, the cops never show up. The Rotters Club remains punk’s neutral territory, a clubhouse of sin in an uptight government town.

For the second time in the four years I’ve spent doing interviews for this book, I find myself in the conference room of a fancy Bay Street office in Toronto. My attempt at dressing professionally (a button-up shirt, balanced by visible holes in my shoes) becomes immediately laughable as I sit down on an exquisite leather couch and wait for Stuart Smith, a high-powered commercial real estate agent with an iPad glued to his side. Smith is, for all intents and purposes, the architect of the Ottawa punk scene. He founded the Rotters Club, the city’s underground punk enclave, and ran a recording studio just inside the Quebec border, where he recorded almost all of the city’s bands, along with the touring groups who passed through the Canadian capitol.

Today, Smith sells land, and judging from the size of his watch, he’s pretty good at it. But like my other bizzaro Bay Street punk experience (with Mods drummer and big-shot entertainment lawyer David Quinton-Steinberg), there’s an immediate connection, something that transcends the cost of the couch, the watch, or the holes in my sneakers. I don’t really belong in Smith’s office. In fact, I appear ridiculous in it. But as we trade stories about D.O.A., Teenage Head, and great Ottawa bands like the Bureaucrats and the Red Squares, the distance between our worlds shrinks dramatically. He’s in a suit and I’m in Levi’s, but it’s another reminder that punk is a culture that is founded on community. Punk exists to bring people together under a common banner, be it politics in Vancouver or drugs in New York. At the core is a passion for music and a lifelong love of alternative culture, and that doesn’t change, even here on Bay Street. I ask one question about the Rotters Club, and I set Smith off on over an hour and a half of tales of debauchery that I can’t imagine get told often in this office. Here’s hoping his underlings never read this.

The Rotters Club was founded in summer 1977, located underneath a Lebanese restaurant on Bank Street. The brainchild of British transplant Stuart Smith, his business partner Carl Schultz, and aspiring comedian Michael MacDonald, the club was designed to give all three an opportunity to pursue their respective passions; the first show featured film, music, and comedy. Crucially, the Rotters Club was also started as a reaction to Smith’s negative experiences in the early ’70s as a touring musician fighting against a powerful local musician’s union that had hindered his career more than helped it.

“One of the guys in our group inherited some money, and he brought the first Mellotron into Ontario,” says Smith. (The Mellotron was an early sampling keyboard, replicating full octaves of a recorded sound using magnetic audio tape.) “The musicians’ union heard about this and said, ‘Sorry, you can’t use that.’” The union wanted Smith’s bandmate to pay union scale for every single finger at every gig he played, reasoning that each note he could play was taking away a job from a working string player. The Musicians’ Association of Ottawa-Gatineau, AFM Local 180, had the same stranglehold in Ottawa that they had in the Maritimes, blacklisting bars that hired non-union talent or refused to pay union scale. The consequence was a closed scene: No punk band could find a bar to hire them at a bloated union rate, even if they could have afforded to pay dues in the first place. (They couldn’t.) So when Smith finally settled himself in the city after half a decade on the road, he was ready to tell the union where to stick it.

“We simply said to the union, ‘Go fuck yourselves. We don’t care who you are. We don’t care what you do. We’re never going to deal with you ever. Your days are numbered.’ We didn’t even know how outrageous that was at the time.” It wasn’t just outrageous, it was prophetic; punk was part of the slow loosening of the American Federation of Musicians’ grip on the live music circuit in North America. The appearance of a viable alternative culture meant that bars no longer had to concern themselves with the AFM blacklist. Punks were drinking as much beer as anyone else, and that was good for the bottom line.

Altruism and rainbows weren’t the only motivating factors that led Smith, Schultz, and MacDonald to the Rotters Club. They had also invested in a studio in Smith’s basement in Larrimac, Quebec, about a half hour from Ottawa. The space was designed to give new bands an option somewhere between a tape deck in the practice space and a bank-breaking professional studio; with an 8-track in a house in a small town, they hoped to lure upstart bands with reasonable prices and quick, high-quality recordings. Of course, thanks in part of the musicians’ union, there were no new bands needing to record. So they created a space designed specifically to foster new talent. And it worked immediately.

“We would only allow bands that played original music to perform,” says Carl Schultz. “Suddenly, there were lots.”

“We never treated it like a business proposition,” says Smith. “We saw it as a way of getting original music front and centre and getting away from the cover bands in bars that had blighted our musical careers and our experiences in music. We were all fed up with it.”

The Rotters Club immediately gained a reputation as an anything-goes den of depravity; the washrooms were co-ed, and more than one person recalls walking in on people having sex in the middle of the room. Pot smoke filled the club, and alcohol was served until three or four in the morning, well after the city’s official last call. Smith is under the impression that the restaurant owners above the club had a “special relationship” with the Ottawa Police Service, a mutual understanding that seemed to be working to everyone’s advantage.

One regular character at the club was known as the Puppet, named for his marionette-like dance moves. He would start every night in a long, jet-black rain coat, and by the end of the show, would be marionetting in a skin-tight black leotard. Another couple were well known for their abuse of Quaaludes, which regularly led to them being passed out and intertwined at the foot of the stage, and once saw them fall down a full flight of stairs before stumbling off into the night. I’m told that someone once pogoed so hard that their head got stuck in the low tile ceiling, and that the son of a local psychiatrist would regularly bring crushed-up Ritalin to shows for the bands. There was a New Year’s Eve party with Johnny and the G-Rays from Toronto where two audience members left the show in an ambulance, the result of kidney failure and alcohol poisoning. There are persistent rumours that Margaret Trudeau visited once during the “Mick Jagger years,” and endless speculation for the reason that the cops never visited.

A regular feature of the club was National Film Board movies, which would be screened before bands every night. One evening, a sweet young couple began to make love behind the screen, their silhouettes visible to the entire audience. When their movements became too powerful, the screen was knocked over; the couple was asked to take it elsewhere.

But even more importantly than uppers and public sex, there was music.

Both the Action and the Bureaucrats had been attempting to gig sporadically before the appearance of the Rotters Club. Along with the Red Squares, they formed the foundation of the Rotters Club scene, each occupying a distinct part of the expanding punk universe. The Action was a sleazy, New York Dolls–esque group who practised endlessly, not wanting to sacrifice the quality of their live show for the quality of their depraved image. The Bureaucrats resembled the Nerves, a tightly wound power-pop group with a dark edge. And the Red Squares were the token art weirdos, a mix of the Talking Heads and Captain Beefheart — though their only recording sounds nothing like that.

The most effective locals at marketing themselves, the Action has survived; they regularly appear on festival bills as “Canada’s first punk band” (often with the caveat of “self-described”). Doubtless that they work as hard today as they did in 1977, and while their approach emanates an undeniably meretricious quality, it’s grounded in a genuine love of first-wave punk and a unimpeachable work ethic. The Action is all about a good story and a pose, and they have the songs to back it up.

When I get vocalist Ted Axe on the phone, it’s like he never missed a beat between our conversation and 1977. He’s as seasoned as the full-time professional musicians I interview for my day job, and I know he’s not doing 15 other interviews today. But Ted Axe has an image to sell and a story to tell, and he is remarkably, admirably, effective at both. He spent 1976 squatting in London, England, attending the notorious

100 Club Punk Special, the two-day coming out party for English punk where bands like the Clash, Sex Pistols, and the Buzzcocks rocketed to national prominence. Returning to Ottawa with a fire inside him, Axe looked to kick-start the same kind of scene in his hometown.

“Coming back to Ottawa was ludicrous because nobody had even heard of punk,” he says. In search of a creative outlet, Axe auditioned for a Stones-y blues rock band called the Action and didn’t make the cut. He went away and practised for three weeks. When he returned, he was invited to join the band. Under his guidance, the Action began to skew their sound toward Axe’s new set of influences, drawn from his time abroad and voracious appetite for whatever was being spit out of the Bowery on a monthly basis. The band didn’t try to entirely shed their original blues flavour, creating a sonic mix similar to the Dolls or the Stooges. They wrote a handful of sloppy originals and set out to destroy the world.

Their first booking came from the Chaudiere Club in Aylmer, Quebec, ostensibly providing the soundtrack for the comings and goings of bikers and prostitutes. For Axe, it seemed a perfect fit, but in order to get through their three 45-minute sets each evening, they began writing at a furious pace. Plus, there were always new era classics by the Ramones and the Damned to pad things out. It didn’t take long to develop a dedicated audience, with stints opening for Toronto bands like the Ugly and the Mods helping to put the band centre stage in front of equally disenchanted new music fans looking for a local band to call their own.

Soon, the band was making moves outside of Ottawa. Travelling to a high school in rural Ontario in the fall, Axe smashed a series of student-carved jack-o’-lanterns, pretended to go down on his bandmates, and vomited on the stage. On the drive back home, he had the bright idea to call the

Ottawa Citizen

and suggest that they had been banned from the musician’s union for their gimmicky antics. Axe claimed that their ousting from the American Federation of Musicians, a kiss of death for any band hoping to make it in the Ottawa bar circuit at that time, made the Action the city’s first punk band. The ensuing press was exactly what the band hoped for, a rich series of adjectives essentially calling them no-talent perverts.

The band’s notoriety began to spread beyond the beltway, and on a trip out to Montreal, the band met Tony Roman. A Quebecois pop singer who was looking to invest in punk with his new record label, Montreco, Roman viewed the spectacle of the Action as the ideal investment — an image-conscious group to live out the label’s punk fantasies. In the end, Montreco only signed two bands — the Action and the Viletones.

“We managed to sign probably the worst record contract in the history of rock,” says Axe. The band only recorded four songs with the label, who released it with a cover that simply read “Punk.” Evidently, Montreco’s business plan involved getting records into department stores for curious non-musical folks to discover. The result just looked silly. Still, the Action continued to command significant crowds in Ottawa, taking up the mantle of the city’s best-known punk act, popular enough to share a label with punk’s Torontonian public enemies. Their shows at the Rotters Club became floor-to-ceiling spectacles.

“We had groupies come in, and I was doing some blow that they had provided,” Axe says. “I heard our set start, and I ran to the stage. When I jumped, I landed on the mic stand, and it whacked into my chest and I broke a rib. I was lying on the ground while they were clapping. They thought it was all part of the show. I couldn’t move. I had to be taken out in an ambulance.”

But the band was falling apart, not the least because of the massive amount of cocaine being consumed by all parties and Montreco’s failed marketing plan. They did manage a string of Canadian dates opening up for the

Stranglers, but a scheduled 1978 American tour with the

Ramones fell through when the band tried to cross the border without the proper paperwork. According to Axe, they were turned away from Sarnia’s Blue Water Bridge as they tried to get to a show in Flint. After getting rejected again at the Windsor-Detroit crossing, they resorted to — his words — going down to the Detroit River, where the band claims that “some guy took us across in a boat to the other side.” If you ask the Action, they rowed their way into America and successfully played 20 dates in the U.S. with the Ramones, including a show at CBGB in New York City. Problematically, the Ramones only played Flint once in 1978, and two weeks later, they were on a plane to Helsinki. They also didn’t play CBGB once that year. Here’s the thing — even if the whole story is a lie, it’s an awesome one to continue to perpetrate over 30 years later.