Pete Rose: An American Dilemma

Read Pete Rose: An American Dilemma Online

Authors: Kostya Kennedy

Tags: #BIO016000, #Bisac code: SPO000000, #SPO003020

Copyright © 2014 by Kostya Kennedy

Published by Sports Illustrated Books,

an imprint of Time Home Entertainment Inc.

Time Home Entertainment Inc.

135 West 50th Street

New York, NY 10020

Book design by Stephen Skalocky

Indexing by Marilyn J. Rowland

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

ISBN 10: 1-61893-096-6

ISBN 13: 978-1-61893-096-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013949234

Sports Illustrated is a trademark of Time Inc.

For Kathrin Perutz and Michael Studdert-Kennedy. For each and for both.

Also by

Kostya Kennedy

56

Joe DiMaggio

and the

Last Magic Number

in Sports

Contents

Chapter 5

Black and White and Red All Over

Chapter 16

Main Street to Marion

Chapter 20

His Prison Without Bars

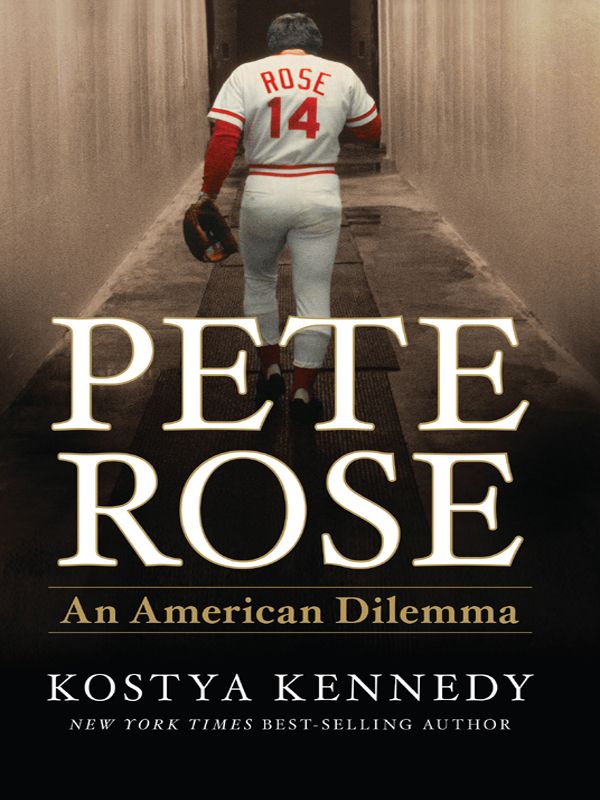

Pete Rose, age 31.

Introduction

“Pete, you’re the greatest. In our house you’re already in the Hall of Fame.”

—Harriet, customer at The Forum Shops, Las Vegas

“People who want him in the Hall, they don’t understand. If he gets into the Hall of Fame there’s nothing that means anything.”

—Goose Gossage, pitcher, Hall of Fame 2008

M

ORE THAN a quarter century has passed since Pete Rose swung a bat in the major leagues, and nearly that long since he filled out a lineup card as a major league manager. He has been banned from base-ball since Aug. 23, 1989. Yet even now, 25 years into exile, he remains a figure who stirs uncommon passion, righteousness, indignation. He remains the subject of perhaps the most polarizing and provocative question in sports: Does Pete Rose belong in the Hall of Fame?

The Rose debate, of course, transcends statistics and performance. This is not a sports discussion on the order of “Who was the greatest quarterback ever?” Or, “Should the American League abolish the designated hitter?” This is something larger than that—unique in its weight and its parameters, a moral conundrum that over the course of its long and changing life has burrowed through every level of the game and expanded far beyond sports talk.

Rose got more base hits, played in more games and came to bat more times than anyone in baseball history. He played with an abandon—a singular and unquenchable joie de vivre—that riled some but endeared him eternally to generations of fans, teammates and opponents. No one, not even Rose’s fiercest detractors, questions his on-field credentials for the Hall of Fame. That would be absurd, like asking whether John Glenn belongs on the list of alltime astronauts or whether Bugs Bunny deserves a place among the cartoon elite.

Rose is also a lifelong gambler and during his time in baseball he bet often and illegally on the game—flouting its explicit prohibition, committing baseball’s cardinal sin, endangering the integrity of the sport. For years Rose denied, often dismissively and defiantly, that he had ever bet on baseball. Then, in 2004, he admitted that while managing the Cincinnati Reds he had wagered not only on the game but on his own team. Rose has often revised details of his recollections along the way. He may say one thing today, something else tomorrow.

So Rose’s story has shifted and still shifts in its particulars, even as the debate around him has slipped and continues to slip into new frameworks. The conversation changes not just as Rose’s story changes, but as the game changes, and the times change, and as our perceptions of athletes evolve.

Most pointedly to the Rose case, the Steroid Era has wreaked a complicated havoc on baseball and on how players are seen and judged. Dozens of ballplayers have now been suspended for using performance enhancing drugs, receiving punishments that to many seem paltry when held alongside Rose’s permanent ban. And several superstars known for steroid use have been made eligible for the Hall of Fame, having committed a different sin from Rose’s—cheating. Although steroids have twisted player legacies and darkened the hallowed records and results that sit at baseball’s core, those drug users have been granted something that Rose, rightfully or not, was never granted: a place on a Hall of Fame ballot. This, even though Rose did not stain the game in the way those drug users did. Or did he?

So, what do we think of Rose now, in this new era, in this redefined world? What do we think of him now, in his 70s and deep into a strange, sometimes slapstick postbaseball journey that has led him to prison for tax fraud; to the pro wrestling ring; to the dog track; to divorce from his second wife; to a reality television series pinned in part to the surgical fate of his young girlfriend’s breasts; and to so many instances of hawking one thing or another, selling his signature, his story, himself? What do we think of him now, the Hit King who still adores and reveres baseball—its nuances, its history—as he adores and reveres nothing else? What do we think of Pete Rose today, in the noisy twilight of his remarkable, original, powerful and wholly American life?

The Rose predicament leads to big questions. What is the price of sin? And, What price is just? Should forgiveness be granted only to the contrite? Does someone deserve harsher punishment for having coldly let down his followers, for having fallen from especially great heights? Should a false apology carry more weight than none at all?

Does it matter whether or not we approve of Rose? Does it matter whether he is selfish or generous? Does the continually indulged gambling compulsion that has shaped him deserve our sympathy or our scorn?

What drove Rose so forcefully to greatness and to his demise? Why has he denied himself his own redemption? Rose could have carried out his extraordinary life in any number of ways. He could have been any kind of hero. Why this?

From the start, and increasingly over the years, the Rose dilemma has tested not only our ethics and our view of morality, but has also led us to the measuring of a man. What would each one of us have done along the jagged path from exposure to banishment to judgment had we been hustling around in Rose’s shoes? What do we think of Pete Rose now?

Chapter 1

Cooperstown, 2012

R

IGHT ABOUT at the center of Main Street in Cooperstown, N.Y., diagonally across from the old Cooperstown Diner, next door to the Double-day Cafe and 396 feet from the three wide stone steps that lead to the entrance of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, sits one of the village’s numerous baseball merchandise and memorabilia shops: Safe At Home Ballpark Collectibles. Here you can purchase all manner of items summoning baseball’s past as well as its present: There are scores of ball caps (a Cubs one with a Wrigley Field logo stitched onto it, a Mets cap from ’69, numerous Red Sox variations) and even more player jerseys (Mays, Musial, Pujols, Jeter…). You can choose from an array of bobbleheads and figurines, wristbands and socks, pens, auto-graphed baseballs and photographs, a trove of miniature helmets. The store sells panini presses that can imprint a team logo onto the toast (“I’ll have a turkey and Swiss on whole wheat, with the Cardinals’ interlocking STL branded into it please.”). This is one of several Cooperstown shops that carries a series of three Abbott and Costello jerseys, each with a respective name and number on the back to honor the duo’s famous routine: “

WHO 1

”, “

WHAT 2

” and “

I DON

’

T KNOW 3

.”

The retail space at Safe At Home runs narrow and deep, and after sidling past many rows of hanging jerseys and T-shirts you come—on Hall of Fame induction weekend, the busiest weekend of every year—to a make-shift partition: a rack of pennants and key chains and other knickknacks. Beyond that there’s some carpeting on the hardwood floor and then a folding table covered by a bright blue cloth, at which, for several shifts throughout the weekend, you can find, sitting and joking and signing for a fee, Pete Rose.

The proprietor of Safe At Home, Andrew Vilacky, is a pal of Rose’s. “When Pete first came up here in the 1990s, there was a lot of controversy— and excitement,” says Vilacky, a wiry, streetwise sort in his mid-40s. “He would step out of his car on Main Street and people would cheer and throw up their arms like someone had just scored a touchdown.”

“There were also a lot of people who were bothered by it, like, ‘What is he doing here?’ ” recalls Bill Francis, a researcher at the Hall of Fame. “People found it distasteful. There is still some of that.”

Rose, like numerous other baseball stars, has been signing for dollars during induction weekend off and on since 1995, when he debuted at a modern Cooperstown institution called Mickey’s Place. He had originally planned to sign there in ’93—less than four years into his lifetime banishment from baseball and just two years after he was made ineligible for induction into the Hall of Fame. He canceled those first appearances, however, after objections from many in the game (including Hall of Famer and former Rose teammate Tom Seaver) who said that Rose’s joining the dozens of former big leaguers peddling their autographs in Cooperstown that weekend would, under his particular circumstances, be in bad taste. Upon deciding to stay away, Rose issued a statement saying that he didn’t want to do anything that would take away from that year’s inductee, Reggie Jackson.

1

After Mickey’s Place, Rose moved with Vilacky and Vilacky’s mentor and business partner, Tom Catal, to the short-lived Pete Rose Collectibles, and then, about five years ago, to Safe At Home. Still, he has not been a constant fixture. For a while in the mid 2000s, Rose believed, based upon conversations with commissioner Bud Selig and other base-ball executives, that he had a chance to gain reinstatement to the game. Rose got the impression from Selig that it would be in his best interest to lie low for a while and not to do things like hold autograph sessions down the street from the Hall of Fame during induction weekend. So for a few years Rose didn’t come to town. Reinstatement, though, never happened, and the prospects that it

would

happen seemed to fade.

Rose, impatient and irked—

pissed

in the words of one person close to him—phoned Vilacky and said, “Fuck it. They’re not doing what they said they would do. I’m coming back up this year.” Over a few days of signing autographs in Cooperstown, depending upon the crowd, Rose might make $30,000 or more.

The arousal that Rose generates by his appearances during induction weekend has abated in recent years, but only slightly. He still attracts a heavy and ardent following—and generates more conversation than the other baseball greats signing their names—and this was particularly true on the late July weekend of 2012 when thousands of Cincinnati fans flooded into Cooperstown to honor the induction of shortstop Barry Larkin, who played for the Reds from 1986 through 2004. As a Cincinnati rookie, Larkin hit his first major league home run in the same game in which Rose, then the Reds’ player-manager, swung at his final big league pitch. Larkin played his first four seasons under Rose, becoming an All-Star.

“That first year we had two shortstops, Barry and Kurt Stillwell,” Rose recalled in Cooperstown the day before Larkin’s induction. “Barry came into my office one day and said, ‘Pete, Kurt is a good player, but you may as well trade him. I’m going to be your shortstop here for the next 15 years.’ We traded Stillwell the next season.” Larkin in 2012 was the first Reds player to go into the Hall of Fame since Tony Perez in ’00. (Sparky Anderson, Cincinnati’s manager for nine seasons and four World Series appearances, was also inducted that year.) Replica Larkin jerseys hung prominently in the storefront at Safe At Home all weekend, as did T-shirts that read

VOTE PETE INTO THE HALL OF FAME

on the front, and

THE ALL-TIME HITS LEADER NOT IN COOPERSTOWN?

PLEASE

on the back.

Rose, per custom of the trade, commanded varying prices for his signature: on a photo or ball ($60), on a bat or jersey ($95), and so on. A personalized inscription might run an extra $20. To get the autograph you bought a ticket at the Safe At Home register, then were led outside and around back to wait in line in an alleyway behind the store. (The reason for this, as Catal, the store owner, explained while surveying the scene from the store’s front step, was so as “not to clog up all this beautiful foot traffic” on Main Street.) Complained one fan wearing a Reds’ Sean Casey jersey that Friday afternoon, “I went back there and checked it out. The line is too long, I’m not doing it.” But a few minutes later he and his companions, similarly clad, had changed their minds and were standing in the line, items in hand to be signed, partially shaded from the high sun on a beautiful summer afternoon.

To each customer Rose provides generous sit-down time and excellent banter. The few minutes next to Rose is a major part of what people pay for—the monetary value of his autograph has slipped significantly after so many years of signing—and also why the line moves slowly. In effect, Rose is receiving visitors. Burly, quick-witted and genial, he never hurries people along, gently needling (“That’s a hell of a wristwatch you got there, what’d it come free with the shirt?”); answering all manner of baseball related questions (Q: “Who is the best player you ever managed?” A: “Me”); and often offering a little something more. (“Do you want to take another photo? Sure, bring both of your kids into this one.”) He’ll give a young ballplayer advice (“Watch the other team’s pitcher the whole time before you come up, you’ll learn something”), and at the end of the exchange he will hold a customer’s handshake for just that extra moment. When he thanks someone for coming out he looks him straight in the eye.

Rose is not avuncular—he’s too crass and not soft enough for that; and although he is advancing deeper into the eighth decade of his life and his children have produced five children of their own, Rose is certainly not grandfatherly. In Cooperstown he wore a lightweight fedora covering up his dyed, reddish hair, and an oversized T-shirt and jeans. Also a thick gold watch. He is prone to telling crude jokes and he is not at all above saying, in mixed and even unfamiliar company, “Right now, I could use a blow job.”

There’s a scruffy sort of soulfulness about Rose, though, something genuine and to admire, and, because of his many sins and because of the strange company he sometimes keeps, there is an aura of mystery too. The broad strokes of his life story—his inspiring self-propelled rise and his astonishing self-inflicted fall—continue to render him an object of deep curiosity. Customers in the store who aren’t waiting to get autographs hover 40 feet away from his signing table, peering over and talking to one another about Pete as a hell-bent ballplayer or about his betting habit or his current romantic involvement with Kiana Kim, a former

Playboy

model who is more than 30 years his junior. “How much money do you think he has gambled away in his life?” someone asks another. “Millions?” There is no need to speak softly, Rose is out of earshot, but the onlookers do, heeding to a sense that they are talking about something they should not be talking about, the details of someone else’s iniquitous life. It’s a bit like the cocktail party guests standing together at Gatsby’s mansion when one woman whispers, conspiratorially, of the host, “Somebody told me they thought he killed a man once.”

Rose is hardly the only lure for autograph seekers this weekend (although he is, even now, arguably the most popular). Main Street is lined with choices. Within a single block a passerby might over the span of a few hours have the chance to get the signatures of Hall of Famers Juan Marichal, Lou Brock, Rollie Fingers, Johnny Bench, Frank Robinson, Goose Gossage and others. A restaurant is offering, just off its outdoor patio, a series of sessions with former Reds such as Eric Davis, Dave Parker and manager Lou Piniella. Big Cecil Fielder, the former Tigers slugger, has a table. There are lines for all of them. Farther down the road is a grouping of players meant to appeal to Yankees and Mets fans: Elliott Maddox, Ron Blomberg, Roy White and Howard Johnson. In front of a memorabilia store called Legends Are Forever a young woman hollers out, carny barker style, “Ernie Banks here from 1 to 4 o’clock. A Hall of Famer! Get your Ernie Banks autograph!”

The hawking of things, the sheer volume of memorabilia and all the money changing hands reveals a Cooperstown greatly altered from the quieter heather-strewn hamlet that officially welcomed its first Hall of Famers on June 12, 1939. Fifteen thousand people spilled onto the festively adorned streets that day—onto Chestnut, Railroad and Main— crowding to try to get glimpses of men like Babe Ruth, Napoleon Lajoie, Walter Johnson and Cy Young. Schoolchildren let out early on that Monday hustled about looking for autographs, but there were no signing tables, no price structures, no thoughts of resale or estimations of value beyond that value which is evident to a child holding, or showing to a friend, a scrap of paper onto which Ty Cobb, say, has just scrawled his name. Today’s scene, with collectors noisily comparing their wares, is a transformation not only from that seminal day, but also from the Cooperstown of the 1960s, ’70s and into the ’80s, before the influx of memorabilia shops and before the autograph and collectibles market went haywire.

In another sense, though, in a feeling, the Cooperstown induction experience is at its core unchanged. Baseball remains a community and on this special weekend, everyone is welcome—the alltime greats, the everyday big leaguers, the Sunday adult leaguers, the fans. Just as Yankees manager Joe McCarthy and recently retired Pirates third baseman Pie Traynor ran into each other and sat to chat on a Cooperstown bench in 1939, Hall of Famers Tony Perez and Andre Dawson stopped for an impromptu conversation in front of the Doubleday Cafe in 2012. Just as fans, come from afar and sparked by the heroes mingling among them, called out then—

Hey Babe! Hey Ty!

—so do they now:

Hey Eck! Hey Whitey!

For all its commercialism, induction weekend can still provide a fine measure of surprise and closeness, a commingling of history, legend and memory, and a prevailing spirit that draws its strength from so many baseball lives. The spirit was there when Connie Mack went in in 1939, and Jimmie Foxx in ’51 and Jackie Robinson in ’62 and Barry Larkin in 2012.

Out on the street in Cooperstown, Rose hears lots of ballpark chatter directed his way. “Whaddya say, Pete!” and “Gotta get you into the Hall, Pete” and of course, inevitably, “Who do you like in the Reds game tonight?” and “What are the odds they’ll win the division?” followed by laughter. Naturally on this weekend there are many references to his hometown, to which he remains so closely associated, and where his idol is most powerful. “Pete, Pete!” a fan calls out. Rose is standing just in front of the glass door outside Safe At Home with Kiana Kim. It is early evening, and he is done autographing for the day. They are going out for dinner with Kiana’s kids. The fan is in his late 20s, sinewy and tough, roughened around the mouth, tattoos running along the inside of both forearms. He has on a white tank top and when he sees Pete look up at him, showing a grin and a thumbs-up, the fan raises a fist and shouts in a raspy hoot, “Cincinnati, baby! West Side!”