Peter and the Shadow Thieves (27 page)

Read Peter and the Shadow Thieves Online

Authors: Dave Barry,Ridley Pearson

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Action & Adventure

THE DRUNKEN CENTIPEDE

W

HEN HUMDRAKE WAS satisfied that al twelve prisoners were securely attached to the chain by their ankles, he opened the jail-cel door.

“COME ON, COME ON,” he bel owed, yanking the first boy forward, thus setting the entire group into stumbling motion. “THE MAGISTRATE AIN’T GOT ALL DAY.” Trying to coordinate his steps with the boys ahead of and behind him, Peter shuffled forward, fol owing Humdrake into a dim corridor, then out into the noisy disorder of the front room of the police station. It was a chaotic mass of London lowlife—pickpockets, footpads, cracksmen, dragsmen, rol ers, beggars, lurkers, swindlers, mobsmen, and more—al loudly proclaiming their innocence while being duly ignored by the burly bobbies who had col ared them.

The sad parade of prisoners drew little attention as, prodded by the impatient Humdrake, they shuffled, chains clinking, through the room to the big front door, then out into the muddy street. It was early afternoon, but typical y dark and gray. A horse-drawn carriage clopped by; Peter and the others ducked, trying to avoid the clods of muck sent flying by the horses’ hooves.

“MOVE ALONG,” bel owed Humdrake. “MOVE ALONG.”

And move along they did, shuffling slowly forward. With each step, Peter grew more desperate, casting his eyes left and right, trying to think how he might escape, his mind refusing to yield a plan.

They crossed several side streets before reaching an imposing gray court building, where Humdrake halted them. A steep flight of steps led up to a massive oak front door. At the top of the steps a distraught young woman, dressed in rags and holding a screaming baby, was clutching at the sleeve of a man in a guard uniform.

“They can’t take him away!” the woman cried. “They can’t take him! How am I supposed to live? How can I feed my baby? My baby is sick! Please—”

“Off with you!” said the guard, giving the woman a shove that sent her staggering. She col apsed and sat on the steps, sobbing, holding her bawling child.

“ALL RIGHT, THEN,” bel owed Humdrake, kicking the nearest of the prisoners—the boy right behind Peter—to get the line moving. “UP THE STEPS. MOVE ALONG!” Clumsily, hobbled by their chains, the prisoners began ascending the steps, past the sobbing woman. She raised her head, and Peter’s eyes met hers for an instant; he saw her despair and felt it in his own heart. Up they trudged. They stopped at the top of the steps, and the guard began to swing open the massive door.

“GET INSIDE, THERE,” bel owed Humdrake.

Peter felt the world closing in on him, his mind searching frantical y for a way out.

“MOVE!”

As if guided by an unseen force, Peter’s hand went to his neck, touching the familiar spherical form of the golden locket. It had been given to him by Mol y’s father, Leonard Aster, on the day Peter had decided he would stay on Mol usk Island rather than return with the Asters to England. Peter remembered Lord Aster’s words: “You may wel need starstuff someday,” he’d said, fastening the locket around Peter’s neck. “Keep it with you always, and use it wisely.” Peter wondered: should he use it now? Its powers were astonishing, but also unpredictable. Would they free him from these chains?

“MOVE ALONG,” bel owed Humdrake.

The first boy in the chain line stepped through the doorway.

Peter made up his mind. Swiftly, he lifted the chain over his head. Holding the locket in one hand, he flicked the tiny catch with his thumb. The locket opened, and Peter’s hand disappeared inside a sphere of glowing, golden radiance. In a moment, al of Peter’s physical discomforts—the cold, the hunger, the pain—were gone, replaced by a feeling of exquisite wel -being. The air around him was fil ed with the delicate scent of wildflowers in a meadow, and haunting musical sounds—neither instrument nor voice—of unearthly beauty.

Peter had experienced this sensation before, but stil , its sheer gloriousness momentarily stunned him. His feet stopped moving, thus triggering a chain reaction: the boy in front of him, his right foot having been jerked to a stop, fel forward into the boy in front of him, who fel forward into the boy in front of

him,

the three of them going down in a heap. Meanwhile, the boy behind Peter stumbled into Peter’s back, and each prisoner in line behind him stumbled clumsily to a halt, some of them tumbling to the steps.

“WHAT’S THIS?” bel owed an enraged Humdrake, watching his chain of charges col apsing and staggering about like a drunken centipede. “GET MOVING! GET MOVING!” Peter, forcing himself to ignore the glorious feeling suffusing his body, bent over and gently tapped the open locket against the shackle on his ankle. In the bril iant glow, he couldn’t see what, if anything, had happened. He pul ed the locket away.

His heart sank: the shackle was stil locked. It was, how ever, no longer made of dirty rusting iron; it was now a warm gleaming yel ow. It was gold.

“Lovely,” said the boy in front of Peter, lying on the steps, looking back. Peter saw that he was talking as much about his mood as the golden shackle; he was feeling the effects of the starstuff. So was the boy behind Peter, who began to sing a song Peter didn’t recognize, a lilting tune about a gypsy rover who came over the hil . The boy, who’d never been much of a singer, found that al at once he had a sweet voice, and he sent it soaring across the steps and into the streets, stopping passersby, who marveled at its beauty:

“

He whistled and he sang ’til the green woods rang

And he won the heart of a lady.

”

The song did not, however, please the already furious Humdrake. He did not permit singing, nor displays of happiness of any kind.

“HERE, NOW!” he bel owed, charging toward the singing boy, prepared to do some serious kicking. As he approached the boy, however, his attention was diverted to the glowing sphere in Peter’s hand. Humdrake had never seen a radiant golden sphere in a prisoner’s possession, but he knew instinctively that this was also something he did not permit.

“WHAT’S THIS?” he bel owed, lunging for the glow. “GIVE ME THAT!”

As Humdrake grabbed for his arm, Peter yanked the locket away, causing it to emit a sparkling fountain of light, which drifted upward for a few seconds, then cascaded downward, a shimmering shower, onto Humdrake and the entire chain of prisoners, and the woman sitting on the steps nearby, holding the crying baby.

As the starstuff descended onto these people, three things happened:

The first thing was that the baby stopped crying and started smiling. The mother smiled, too, in grateful relief. She did not know it yet, but her child was no longer sick and would never be sick again.

The second thing was a radical change in Humdrake’s mood. In a flash his anger was gone, replaced by a sense of powerful affection for these boys, these lads, these unfortunate urchins. Their only real crime, Humdrake now realized, was that they lacked a strong father’s hand to guide them—a lack that Humdrake himself had felt keenly as a boy. No, thought Humdrake, these boys were not criminals to be punished; what they needed was direction and, yes, love. And he, Humdrake, could provide it. Take this boy in front of him right now, the scrawny one who tried to steal the toilet bucket. What inner torment the boy must have been feeling to be driven to such a desperate act! What this boy needed, Humdrake now saw, was a hug.

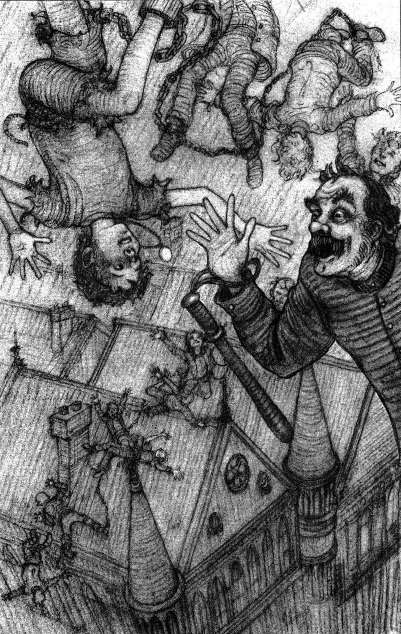

And so Humdrake reached out to hug Peter, only to find himself tumbling forward in a slow and weightless somersault. That was because of the third thing that was happening: Humdrake was rising into the air. So was Peter. So, in fact, were al of the prisoners. They were drifting graceful y upward from the courthouse steps, like the tail of an enormous, strange kite. Some of them were right-side up, and some were upside down, but none were even slightly alarmed. Al were delighting in the experience and the view; the boy behind Peter was stil singing, his high-pitched, bel -clear voice echoing down the street:

“

And here I’ll stay ’til my dying day

With my whistling gypsy rover.

”

The spectacle of a dozen flying people quickly drew the attention of passersby on the street below. There were shouts of surprise and alarm, then some screams; a crowd gathered and grew quickly as the uproar drew more and more spectators from surrounding streets and from the courthouse itself. Kremp, the young apprentice jailer, ran nervously back and forth on the steps; Humdrake had given him no instructions regarding what to do when prisoners floated away.

Peter and the others were now hovering one hundred feet in the air over the increasingly chaotic street scene. Peter had shut the locket and returned it to his neck, not knowing how much of its precious contents he had left, if any. What he did know was that the starstuff now keeping the prisoners and Humdrake aloft would eventual y wear off, and they would drift back to the ground. Before that happened, he needed to get his ankle free of the golden shackle. But to do that, he needed to get the key from Humdrake, who was floating about twenty-five feet away and a little above the others, smiling radiantly.

Peter tried to fly toward him, but he could not move the massive group to which he was attached.

“Sir!” he cal ed, trying to get Humdrake’s attention. “Sir! Sir!”

“YES, BOY,” said Humdrake, stil bel owing, although now it was an affectionate bel ow. “WHAT IS IT?”

“Sir, can you please fly over to us?” said Peter.

“OF COURSE,” bel owed Humdrake, and he began flapping his arms, an action that had no effect other than to make him look like an enormous mutton-chopped penguin.

“No, sir! You have to lean! Lean!” shouted Peter, but Humdrake could no longer hear him over the roar of the crowd below. Hundreds had gathered in the street, with more coming every moment. The boys around Peter were laughing, thoroughly enjoying the wonder of it al , floating above the sea of upturned faces and shouting voices.

Their euphoria was not shared by Peter, who understood, with a sinking feeling, that al he had bought with his precious starstuff was a few more minutes of freedom. The flying chain would come down, and when it did, he would again be trapped, this time for good.

SOMETHING STRONG

M

OLLY GASPED; her hand went to her throat.

This time it was far stronger: a pulsation from her locket, the feeling of heat, almost as if her skin were burning.

Again, she ran to the window and looked out, hoping to see her father. Again she was disappointed.

But she knew something must have happened—something strong and close by. Keeping her hand on the stil -warm locket, she stared into the gloom, her thoughts racing but finding no answer.

What could it be

?

EITHER WAY

T

INKER BELL FELT IT, TOO, but in a different way, and more powerfuly. She was sitting on a roof, resting and fuming after yet another failed attempt to extract information from yet another idiot London pigeon. Then it came: it was as if an invisible wave of warm air had suddenly enveloped her, then rushed past.

Tink knew instantly what it was. She also knew, from its direction of travel, where it had come from. Forgetting her weariness, she leaped up from the rooftop and streaked low across London as fast as she had ever flown. She understood that Peter had opened the locket, or somebody else had.