Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (18 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

S

OCIETY

H

ILL

P

HILADELPHIA

Society Hill started as a place where socially prominent people lived and worked, and it remained so through the mid-1800s. Then the region lost its cachet as the center of Philadelphia moved west. By the 1950s, Society Hill was a slum that predominantly housed poor immigrant families. Noted preservationist Charles Peterson (1906â2004) said that it was a “has-been neighborhood” when he moved there in 1954.

But starting in 1958, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority embarked on an enormous urban renewal project for the precinct. The city acquired crumbling Georgian and Federal houses via eminent domain and sold them to buyers who agreed to restore the buildings according to certain standards. In this way, about six hundred eighteenth-century houses were renovated. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century structures that did not “fit in” were replaced by contemporary houses that sought to combine colonial tradition with modern style.

City planners chose the appellation “Society Hill” to honor the locality's heritage. The district became a true urban redevelopment success story, filled with charming row homes, tree-lined streets and sidewalks of brick and cobblestone. Once again a prestigious neighborhood, Society Hill contains the largest concentration of original eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century architecture anywhere in the United States. Its renaissance sparked the similar revitalization of Old City, Queen Village (Southwark) and the rest of Center City Philadelphia.

S

OCIETY

H

ILL

T

OWERS

The three Society Hill Towers are skyscraper condominiums located between Walnut and Spruce Streets, above Dock Street and interrupting Second Street. Designed by I.M. Pei and Associates, they were completed in 1963 and represented a very different type of building than those in the then-dilapidated Society Hill district. The towers embodied the rebirth and rise of this quarter, replacing dozens of run-down food warehouses from when this region was Philadelphia's main food distribution hub.

Society Hill Towers have become one of the finest residential centers in the world. Perched on a substantial hill (symbolizing the Free Society's hill) and each thirty-one stories high, they would have made a very conspicuous landmark for Philadelphia-bound seafarers in the old days. The complex consists of 624 units, many of which provide some of the best views of Center City and the Delaware River.

This was a rental community until a condominium conversion in 1979. The development includes modern ground-level housing that goes well with the eighteenth-century homes throughout the neighborhood. Modern sculptures embellish the five acres of landscaped grounds.

The neighboring Sheraton Society Hill Hotel was built in the Colonial style and has a four-story atrium lobby. Developed by Rouse and Associates, the hotel opened on July 4, 1986. Over 130 prehistoric Native American artifacts were recovered on the triangular site during an archaeological study before construction.

N

EW

M

ARKET AND

H

EAD

H

OUSE

S

QUARE

In 1745, ground in the middle of Second Street from Pine to Cedar (later South) Streets was designated as a marketplace for the South End's growing population. Market stalls were raised, and the place was named New Market to distinguish it from the High Street Market. A head house at Pine Street was built in 1804â05 for use as a meeting place for volunteer fire companies and other associations and for the storage of fire apparatus. Another head house had been erected earlier at South Street but was taken down in 1860.

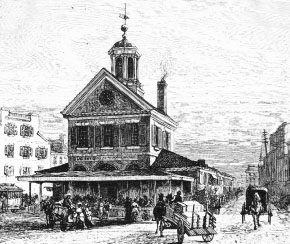

New Market's Head House in the nineteenth century.

From

History of Philadelphia, 1609â1884

(1884)

.

The market sheds were commonly called the “Mid-Street Markets” and the “Second Street Markets.” They were also referred to as the “Shambles,” an old English word for meat markets or butcher shops. Operating into the twentieth century, this covered open-air bazaar was presumably the country's oldest public market before it fell into ruin in the mid-1950s. In 1962â63, half of the Shamblesâbetween Pine and Lombardâwas rebuilt to replicate its eighteenth-century predecessor. The Head House at Pine Street was also restored.

The Head House and shed now signify the heart of Society Hill and provide a venue for community events. The re-created Shambles can still claim to be the oldest market in continual use in America, since it's still used as a farmers market selling locally grown produce. Artists and craftsmen occasionally display their wares there too. Meanwhile, the Head House is said to be the oldest firehouse in the United States.

Declared a National Historic Landmark in 1966, the two-block plaza is called Head House Square nowadays. Shops, cafés and restaurants line both sides of Second Street, many occupying rehabilitated buildings from Philadelphia's colonial past. Comprising some ten acres of historic properties, Head House Square was listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

J

AMES

F

ORTEN AND

H

IS

S

AIL

L

OFT

James Forten Sr. (1766â1842) lived and labored in this neighborhoodâthe east end of Lombard Street. Becoming one of the richest African Americans in America, he was born free in Philadelphia and was educated in Anthony Benezet's Quaker-inspired Negro School at Philadelphia.

Forten was apprenticed in his youth to Robert Bridges, a sailmaker who had a sail loft on a wharf at Front and Lombard. Bridges was pleased with Forten's work and promoted him to foreman overseeing some three dozen employees. With Bridges' help, Forten purchased the shop in 1798. It was unusual for any novice to take over the business where he learned his trade, but it was especially rare for a black apprentice to take charge of a successful white-owned enterprise.

About this time, Forten purportedly began experimenting with different types of sails and perfected one that made ships maneuver easier and achieve greater speeds. He did not patent his invention, but he was able to profit from it since his sail loft became one of Philadelphia's most prosperous maritime businesses. Forten's $300,000 life's fortune would make him a millionaire todayâanother one along the central Delaware.

James Forten was also an abolitionist and a reform leader well before Fredrick Douglass came on the scene. Not only was his sail shop integrated, but Forten also financed a range of antislavery activities. He purchased the freedom of slaves, opened a school for black children and even established an Underground Railroad stop at his home.

The site of Forten's sail loft is now within the footprint of Highway 95. Interestingly enough, the workshop was located a few steps away from where abolitionist Francis Pastorius once lived in a comfortable cave by the water.

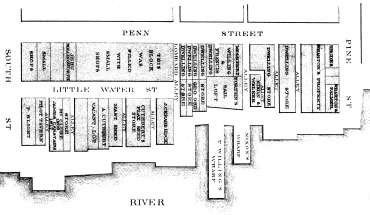

The waterfront from Pine to South Street about 1800, showing James Forten's sail loft business at center right.

From

Philadelphia and Her Merchants

(1860)

.

15

S

OUTH OF

S

OUTH

S

TREET

S

OUTHWARK

H

OSTS A

S

WEDISH

C

HURCH AND A

P

ARTY FOR THE

A

GES

South Street was labeled Cedar Street when Philadelphia was first planned, but people soon started calling it by its present name because it formed the city's (original) southern limit. In the 1960s, South Street became known around the country as “the hippest street in town” thanks to the rock 'n' roll hit “South Street” by the Orlons. (“Where do all the hippies meet? South Street, South Street.”) The South End was cheerfully bohemian back then as it is today.

But trouble was brewing. The Crosstown Expressway, discussed for years, would have obliterated a block-wide swath of the city along South Street from the Delaware to the Schuylkill Rivers. Mayor Frank Rizzo finally canceled this monstrous project in 1974, but the hip street still took a terrible hit as residents and businesses moved away in anticipation of construction. The neighborhood managed to recuperate after the project's termination and South Street again became a trendy promenade with unconventional boutiques and restaurants.

Speaking of unconventional restaurants, the Caledonia Tavern was once on the south side of South Street near Front Street. According to Watson, this was “a great place of resort for Scotchmen” and “had a swinging sign on one side of which was a picture of two friends shaking hands.” The motto beneath was “May we never see an old friend with a new face.”

W

ICACO

/S

OUTHWARK

/Q

UEEN

V

ILLAGE

South Street is part of the Queen Village neighborhood, bounded approximately by South Street, Washington Avenue, Sixth Street and the Delaware River. This is Philadelphia's oldest and best-preserved precinct, as well as the first part of the city to have been settled by Europeans.

In 1669, fur-trading Swedes established a hamlet in this area, which the Lenni-Lenape called “Wicaco” (pleasant or peaceful place). Wicaco (Wicacco/Weccacoe/etc.) was an outpost of the New Sweden colony on the lower Delaware River.

Land by the river was occupied by the Swedish family of Sven, whose log cabin stood on a knoll at what is now the northeast corner of Beck and Swanson Streets. The structure stood for more than a century until British troops used it as firewood during the Revolutionary War.

Wicaco ultimately became the Southwark District of Philadelphia County and then the Southwark section of the city. The name was adopted because of its location south of Philadelphia, an allusion to the similarly situated English borough on the Thames just south of London. The streets and alleys of Southwark on the Delaware sustained a diverse group of artisans, tavern keepers, mariners, shipbuilders, shopkeepers and farmers. Whole blocks developed seemingly overnight in the 1800s.

But like Society Hill and Old City, Southwark hit hard times in the twentieth century. Local real estate agents dubbed the area “Queen Village” in the 1970s to help improve its image and to acknowledge the community's colonial roots. The term venerates Queen Christina of Sweden, who encouraged Swedish colonists to settle the land. Some local holdouts still refer to these environs as Southwark.

Queen Village was the first Philadelphia neighborhood to offer modern housing on the river side of the Delaware Expressway. This is the Court at Old Swedes development at the end of Christian and Queen Streets. Dozens of town house condos were built in the early 1980s on the site of a Pennsylvania Railroad freight yard. The land had previously been a shipyard, that of Simpson & Neil. More new housing is being built there today.

Conversely, the narrow three-story abodes at Front and Carpenter are some of the oldest row houses in Philadelphia. These eighteenth-century workers' houses are called “trinities” (Father, Son and Holy Spirit) because they typically had only one room per floor. New residents of Queen Village have restored many of these humble homes to their original appearance. But alas, about 130 were condemned and pulled down for the building of I-95. The trinities that remain shake when trucks speed by on the elevated freeway slicing through these parts.

Water Street was offset at Pine Street and was known for a time as Penn Street. Another street closer to the Delaware was put in and was first called Larkin Street, then Little Water Street and finally Swanson Street. Like the small houses, corner bars and mom-and-pop grocery stores standing alongside them, most all of these little streets gave way to the Interstate.

M

ILITARY

M

ATTERS

(IV

OF

V): T

HE

S

PARKS

S

HOT

T

OWER