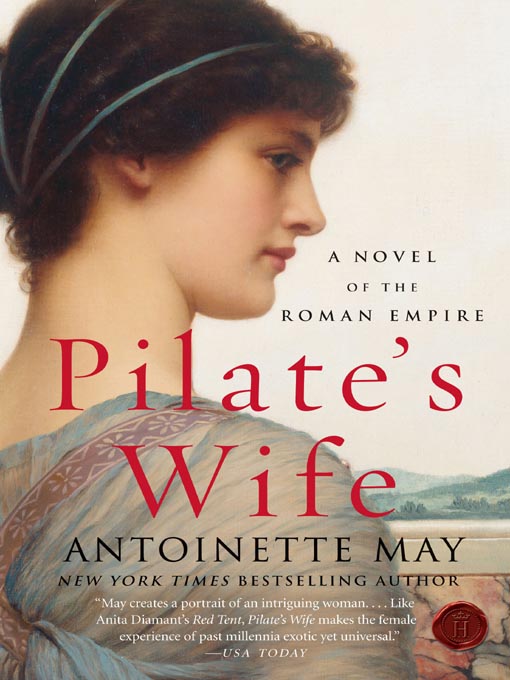

Pilate's Wife: A Novel of the Roman Empire

Read Pilate's Wife: A Novel of the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Antoinette May

Antoinette May

For my husband, Charles Herndon

WHAT IS TRUTH?

--Pontius Pilate

Journalism is a marvelous career. It enables me to be as nosy as I please, delving into old records, newspapers, and letters. My profession enables me to ask anybody anything. Most of the time I get answers that can be corroborated by other interviews and/or checked against recorded facts. Exploring the who, what, why, and how of things has kept me flying since my first newspaper job at fifteen.

Curiosity led from reporting to magazine profiles and biographies. A combination of interviews and archival research resulted in

Passionate Pilgrim,

the 1920s drama of archaeologist Alma Reed;

Witness to War,

the story of Pulitzer-prize winning war correspondent Maggie Higgins; and

Adventures of a Psychic,

a biography of contemporary clairvoyant Sylvia Browne.

A biographer must be a detective as well as a writer and social historian. I began

Pilate's Wife

fourteen years ago as I had my other books--with research. In this case, it involved going back to school. The classics department at Stanford University proved invaluable. For six years I studied with a variety of brilliant professors who opened up the first-century worlds of Rome and Judaea. Steeped in the history, art, philosophy, literature, architecture, and mythology of the time, I then visited the remains of Claudia's world in Rome, Turkey, Egypt, and the Holy Land.

But where was Claudia herself? She was born, she dreamed, she died. Was nothing else known about the visionary wife of Pontius Pilate? For the first time, conventional biography felt constraining. Soon it became apparent that I would have to enter the less familiar realm of the imagination. As I slipped into another world, one by one the questions that were my reporter's stock and trade were answered. Slowly, almost shyly, Claudia revealed herself, allowing me to tell her story.

F

irst, let it be said that I did not attend his crucifixion. If you are seeking insight into that tragic affair, you will not hear it from me. Much has been made in recent years of my attempt to stop it, my plea to Pilate telling him of my dream. Knowing nothing of what really happened, some insist on seeing me as a sort of heroine. They are calling Miriam's Jesus a god now or at least the son of a god.

Jerusalem was a tinderbox in those days. Pilate would have forbidden me to attend a public execution. But when have rules mattered? When has risk stopped me from doing anything that I set my mind to do? The fact is, I could not bear to watch the final agony of...of...who was he really? After all these years I still do not know. Some Jews believed him to be the messiah while their priests cried, "rabble rouser." If his own people could not agree, how could we Romans have been expected to know?

How well I remember Pilate in those days, eyes so blue, mind sharp as the sword hanging from his waist. We were certain that Judaea was only the beginning of an illustrious career.

Isis had other plans. It was a dream of mine that brought us here to Gaul. Yes, of course I still dream. For a change, this one was pleasant. It took me back to Monokos, a village on the Mediterranean coast. I saw myself a girl again, carefree and unafraid, splashing in tide pools, building castles in the sand. Germanicus was there beside me watching as he used to do, the red plume of his helmet fluttering in the breeze. I awakened knowing that Monokos would be good for us.

My solace comes from memories that began here. Sitting alone in the sun, the sea lapping far below, I think often of those days and the momentous years that followed. My granddaughter, Selene, is coming to visit. Yesterday a Roman vessel brought her letter. "You must tell me the whole story," she urged. "Everything."

At first I shrink from the idea. How could I reveal...The days pass, the sea mist cool on my skin, the surf sounds at night. Selene will be here tomorrow. I am ready. I know now that the time has come for me to speak of what has happened. It will be good to set the record straight.

All of it at last.

I

t wasn't easy having two mothers. Selene, who'd given me life, was small, dark, feminine as a fan. The other, her tall, tawny lion of a cousin, Agrippina, was granddaughter of the Divine Augustus.

My father was second in command under Agrippina's husband, Germanicus, commander in chief of the Rhine armies and rightful heir to the Empire. Growing up in one army camp after another, my sister, Marcella, and I were often in Agrippina's home, treated as her own. She favored her sons, but their time was given over to trainers who drilled them daily in the use of sword and spear, shield and ax. We girls remained clay for her to mold.

When I was ten, the ceaseless chatter of the older girls bored me. "Which officer is handsomest?" "What

stola

the most alluring?" Who cared! I was reading Sappho when Agrippina swept the scroll from my hand. Studying my face in the morning light, she admired my profile. "Your nose is pure patrician, but that hair!"

Agrippina grabbed a gold comb from the table, swept my hair this way and that. Then, as I sat rigid under her restraining hand, she began to cut. Slaves scurried to brush away the thick unruly curls fallen to the floor. "Ah, this is much better. Hold the mirror up higher," she instructed Marcella. "Let her see the back, the sides."

Agrippina was always full of ideas, so sure she knew best. I glanced at Marcella, who nodded her approval. The wild hair had been tamed--thinned, pulled back, and bound by a fillet so that my curls cascaded like a waterfall.

Agrippina scrutinized me carefully. "You're really quite pretty--not a beauty like Marcella here, but who knows." She glanced again at my sister. "You're a rose--no doubt about it--but Claudia...let me think. Who

is

Claudia?" She reached into drawers, pulling out scarves and ribbons, selecting only to discard. At last, "Of course! Why didn't I see it sooner? You're our little seer, shy, ethereal--pure purple! This is your color; wear it always."

Wear it always!

Agrippina was so imperious. Her enthusiasm overwhelmed me. It infuriated Mother. "Those were your baby curls!" she stormed angrily when I came home laden with purple tunics, flowers, scarves, and ribbons. And so it went between them, with me always in the middle.

Still, to this day, I favor purple and take pride in my profile.

People who felt entitled, even obligated, to impose their wills on me were everywhere.

Tata

and Mother, of course, but also Germanicus and Agrippina--I called them aunt and uncle. My sister, Marcella, two years older, expected to dominate me, as did our rich cousins, Julia and Druscilla, and their brothers, Drusus, Nero, and Caligula. Caligula missed no opportunity to tease and embarrass me. He liked to put his tongue in my ear and only laughed when I smacked him. Small wonder I coveted my own company.

Perhaps it was from these quiet times that the sight came. At an early age, I often knew of a visitor's approach before a slave announced the arrival. It happened so naturally that I wondered why others were surprised or even suspicious, imagining that I played a joke. Because the knowledge was trivial and rarely benefited me, I thought little of it.

My dreams were different. They began when we were stationed in Monokos, a small town on the southwest coast of Gaul. For a time it seemed that I could scarcely close my eyes without a vision of some sort overtaking me. They were fragmented dreams. I remembered little and understood less, yet awakened always with a chilling sense of impending danger. The frequency and intensity of these nighttime visions increased; I feared to sleep, forced myself to lie awake late into the night. Then, in my tenth year, I had a dream so vividly terrifying that I have never forgotten it or the events that followed.

I saw myself in a wooded wilderness, a fearful place, thick, dark, almost black. Wet leaves scraped across my face as I breathed the damp smell of decay, shivering miserably in the cold. I struggled to free myself but could not; the dream held me prisoner in its thrall. All about me strange and fearful men chanted words I could not understand. As they crowded forward, surrounding me, I saw that they were dressed as legionnaires, but unlike the soldiers in our garrison, their faces were hardened by anger and bitterness. A huge, fearsome man with pockmarked skin came forward, a young wolf trotting companionably at his heels. This awful person urged the others to violence. Answering cries echoed through the dark forest. He grabbed a sword and lunged toward the wolf who sat trustingly at his feet. With one swift stroke, he impaled the unsuspecting creature. The wolf screamed horribly or was it I who shrieked? In the last awful seconds of the dream the wolf became my uncle. It was dear Germanicus who lay dying at my feet.

Though

Tata

and Mother rushed in to comfort me, I couldn't banish the ugly picture from my mind. "Someone wants to kill Uncle Germanicus," I gasped. "You have to save him."

"Tomorrow, love, we'll speak of it tomorrow,"

Tata

promised, stroking me tenderly, but the morning's talk was brief. My parents agreed: a child's nightmare scarcely warranted bothering the commander in chief. Two days later when a messenger brought word of a threatened mutiny in Germania, I saw them exchange troubled glances.

My retreat in those days was a secluded corner of beach obscured by rocks. I went there alone, waded in tide pools where no one saw me but the tiny sea creatures I called my own. This is where Germanicus found me. Dropping down on a rock, eyes level with my own, he spoke. "I understand we have a seer in our midst."

I looked away. "

Tata

says it isn't important."

"I take your dream as very important and will heed its warning." His rough hand touched my shoulder. Germanicus's hazel eyes lit in a smile. He leaned closer, his tone conspiratorial as though talking to an important adult. "We're going to Germania--all of us. Agrippina is convinced that her presence will restore morale in that wretched corner of the Empire. Jove only knows, those poor devils have reason for mutiny. Some have grown children they've never seen..." His voice trailed off.

What was the matter?

I searched the handsome face above me, clouded now, brows furrowed. Timidly, I slipped my hand in his.

Germanicus smiled. "No need for

you

to worry, little one. It will work out, you'll see for yourself. Agrippina needs a woman companion. I've asked Selene to accompany her. And, since my children are going, why not you and your sister?"

M

OTHER WAS FURIOUS

. I

N THE PRIVACY OF OUR HOME, SHE CALLED

Agrippina reckless and absurd. "A woman seven months pregnant making such a journey!" she fumed to

Tata,

unaware that I watched from an alcove. Her face softened as her arms encircled him. "At least I'll be with you--not sitting at home, frantic with fear. It's the girls I worry about. How can we leave them behind when Agrippina makes a show of taking hers?"

I looked about the familiar room as though seeing it for the first time. The walls were a burnished crimson that

Tata

had admired in Pompeii. Mother had painters mix it as a surprise, testing and discarding many times before she was satisfied. Sculpted heads of ancestors watched discreetly from alcoves. Souvenirs from tours of duty added color and nostalgia. There were couches with colorful throws, wall hangings, and cushions in vibrant greens and purples. Mother had created a haven in the midst of an army camp. I didn't want to leave it.

O

N THE FIRST LEG OF THE LONG JOURNEY

, I

RODE IN A HORSE-DRAWN

cart with Mother, Agrippina, and the other girls, my chestnut mare Pegasus tied behind. We played word games to keep our minds busy, but Auntie's voice was louder than usual, reminding us again and again that everything was all right. Mother kept her voice soft, but her eyes flashed angrily at Agrippina. Eventually they abandoned the games, gave us scrolls to read, and whispered among themselves. What I heard was awful: "Mutiny inevitable." What was Germanicus to do?

Gaul's vineyards and pastures gave way to Germania's dense forests. Bushes scratched and scraped like groping fingers. Above us crows and ravens watched. Wild boar scuttled in the undergrowth. I heard wolves howling. Even at noon the light was so dim I felt as though I'd fallen into an abyss. Watching my cousins Drusus and Nero riding with Germanicus, I saw their drawn faces turn often to their father, who nodded encouragement. Caligula rode ahead, brandishing his sword at shadows.

As the days passed, and the leaders guided us through overgrown trails, foot soldiers, two abreast, twisted like a slow sea serpent across an ocean floor. The forced enthusiasm of both Mother and Agrippina frightened me more than the forest. I insisted on riding Pegasus beside Drusus though wretched Caligula jeered at me.

The month's journey across Gaul into the Germanian forests seemed an eternity. At last we reached the outskirts of the mutinous legion's camp. Silently, a few bearded men emerged, eyes guarded.

Not an officer in sight

. Germanicus dismounted, his manner casual, almost jaunty. Motioning his troops back, he approached the men alone.

Tata

's mouth was grim; his hand rested on the hilt of his sword.

The mutineers crowded forward, their voices an angry babble of complaints. A huge man wrapped in ragged fur grasped Uncle's hand as though to kiss it; instead he thrust Germanicus's fingers into his mouth to feel toothless gums. Others, their scarred bodies covered with rags, hobbled about, eyeing me like a food platter. I urged Pegasus forward as one grabbed for the reins. Then I saw a circle of pikes, atop each a decaying head.

The missing officers.

My stomach lurched. More mutinous soldiers moved in, blocking our exit. I clamped my jaws shut to still chattering teeth.

Germanicus issued an order: "Stand back and divide into units." The men merely pushed closer. I saw

Tata

's fingers tighten on his sword and wondered if Pegasus felt my legs tremble. Drusus and Nero rode in closer to their father. My heart pounded. It was going to happen.

Tata

and Germanicus would be killed, and with them Drusus and Nero, who'd always seemed like big brothers, and Caligula who never had. Then those fierce, angry men would move on to me. We were all going to die.

Tata

glanced questioningly at Germanicus. The commander shook his head, then turned, leaping easily onto a large rock. As he stood calmly surveying the scene, I thought him noble in his cuirass and greaves, the plume on his helmet fluttering in a light breeze. Speaking quietly so that the angry men had to be still, he paid tribute to Emperor Augustus, who had recently died. He praised the victories of Tiberius, the new emperor, and spoke of the army's past glories. "You are Rome's emissaries to the world," he reminded them, "but what has happened to your famous military discipline?"

"I'll show you what happened." A grizzled one-eyed veteran strode forward, pulling off his leather cuirass. "This is what the Germans did to me." He displayed a scar on his belly. "And this is what your officers did." He turned to reveal a back lacerated with scars.

Angry cries echoed as the men railed against Tiberius. "It's Germanicus who should be emperor," the ringleaders shouted. "You're the rightful heir, we'll fight with you all the way to Rome." Many took up the cry, banging their shields and chanting. "Lead us to Rome! Together to Rome!" The angry soldiers pressed forward. I shuddered as I saw them roll their swords back and forth against their shields, the prelude to mutiny.

Germanicus pulled the sword from his belt and pointed it at himself. "Better death than treason to the emperor."

A tall burly man, his body laced with scars, pushed forward and removed his own sword. "Then use mine. It's sharper." As the angry crowd closed in around Germanicus, Agrippina pushed her way toward him. A burly soldier more than a head taller sought to bar her way, but she merely thrust her large belly at him, daring any to lift a hand. The front ranks stepped back. Scarred veterans who'd stood with weapons raised slowly lowered them.

As the soldiers cleared a path for her, Agrippina walked proudly to the rock where her husband stood. Father and I dismounted as the men quieted. Mother and Marcella climbed from the wagon and stood beside us. Her wide brown eyes even wider, Mother slipped her arm in

Tata

's. Smiling confidently, she took my hand, calling over her shoulder for Marcella to hold my other hand. We were all trembling.

Every eye turned to Germanicus. He looked so brave, his voice ringing clear and true. "In the name of Emperor Tiberius, I grant immediate retirement for those who have served twenty years or more. Men with sixteen years' service will remain, but with no duties other than to defend against attack. Back pay will be paid twice over."

Soldiers boosted Agrippina up onto the rock. She stood by her husband, the two making a handsome tableau on the great flat stone. "Germanicus, your leader and mine," she said, "is a man of his word. What he promises will come to pass. I know him and I speak the truth." She stood proudly, her face serene despite the silence that greeted her words. At last one man cried out: "Germanicus!" Others joined him, some tossed their helmets high in the air. Their cheers made me want to cry.

"We're lucky,"

Tata

said later. "What if they'd demanded their pay now?"

G

ERMANICUS INSPIRED THE MUTINEERS

--A

GRIPPINA DID TOO, EVEN

Mother admitted that. Hard as it was for me to understand, Caligula, too, was a favorite. He'd been born in an army camp, worn army boots, and drilled with troops when he was still a toddler. Caligula meant "little boots." Now hardly anyone remembered that his real name was Gaius.