Plagues in World History (21 page)

Read Plagues in World History Online

Authors: John Aberth

Tags: #ISBN 9780742557055 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 9781442207967 (electronic), #Rowman & Littlefield, #History

since “the vast majority of people with TB are young and poor and live in developing countries.”31 (This is the subject of the 2005 film

The Constant Gardener

.) Recent sequencing of the TB genome holds some promise for targeting “hiber-nating” bacteria that can lie dormant in the body and thus resist antibiotics, only to be reactivated at a later time, but the full fruits of this research are probably years away. More promising in the near term is perhaps efforts under way to develop a more effective BCG vaccine, which would allow for targeted eradication on the model of the successful campaign against smallpox.32

100 y Chapter 3

Then there are underlying causes of TB, such as poverty, which are far more intractable problems to solve, especially since TB and poverty are closely linked in a mutually reinforcing cycle: TB is said to flourish in the overcrowded, malnour-ished, unhygienic environments that poor people are most susceptible to, while at the same time the disease hits poor families the hardest in terms of lost wage income and increased expenses for medical treatment, often as the result of delayed and incorrect diagnosis.33 Yet, with the many possibilities of global spread of TB

(such as on airline flights), the current crises in poorer nations simply cannot be ignored by richer neighbors. Since TB can be spread so rapidly and easily, with one contact potential y infecting dozens of others in short order, time is of the essence in the fight against the disease. Much of this chal enge is of humankind’s own making, particularly in the case of MDR-TB, where ironically the cure is also our curse. But the consensus seems to be that society can conquer TB, if only it can muster the will, money, and ingenuity to do so.

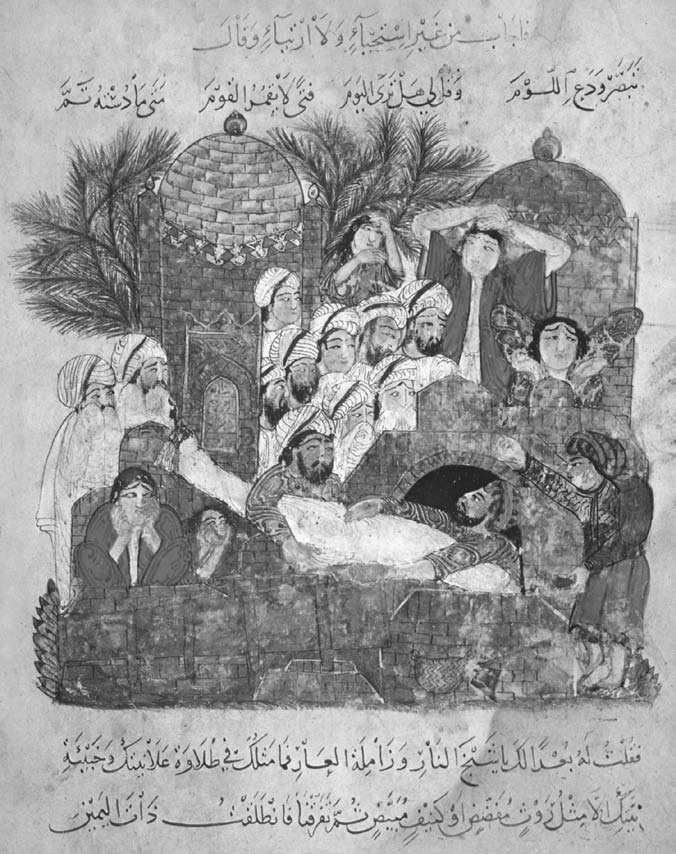

Burial of a plague victim from the

Al Maqamat

(The Meetings) by Al-Hariri, Persian school, fourteenth century. Getty Images

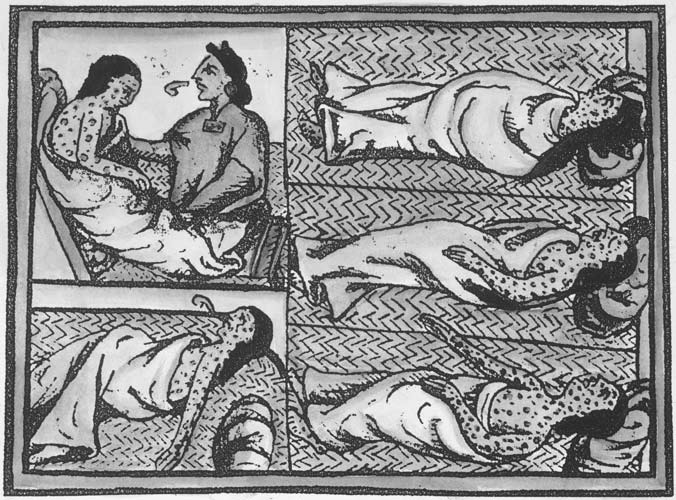

Smallpox epidemic in Mexico. Aztec natives with smallpox contracted from Spaniards are ministered to by a medicine man. Illustration from Father Bernardino de Sahagun’s sixteenth-century treatise,

A General History of the Things of New Spain

. The Granger Collection, New York

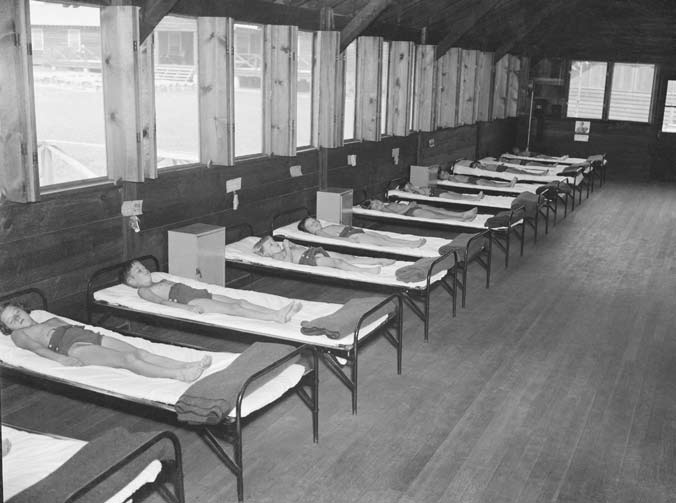

Tubercular children taking enforced rest for fifteen hours each day at a tuberculosis camp in Washington, DC, in 1938. Note the many wide-open windows designed to let in fresh air. © Bettmann/CORBIS

Bodies of Rwandan refugees, who died in a cholera epidemic that spread through refugee camps at Goma in July 1994, await burial in a mass grave near Kibumba camp, Zaire. © Howard Davies/CORBIS

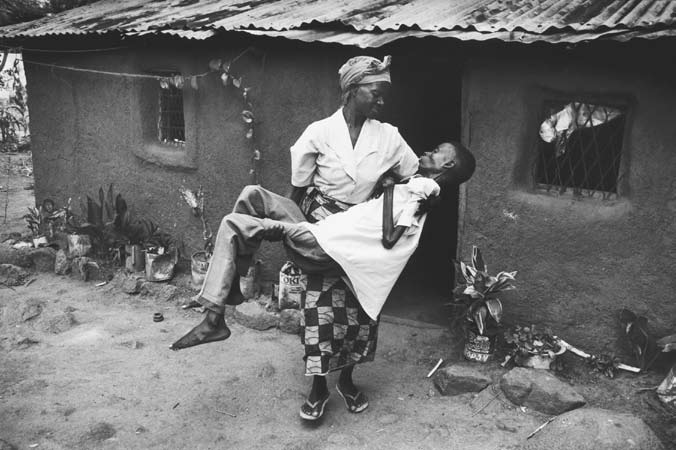

A Tanzanian mother carries her thirty-year-old son, Joseph, who is ill with AIDS, outside to sit in the shade, c. 2000. © Gideon Mendel/CORBIS

C H A P T E R 4

y

Cholera

Like tuberculosis, cholera is a disease often associated with the nineteenth century and is likewise caused by a bacterium, in this case, the comma-shaped

Vibrio cholerae

that was identified by Robert Koch in 1883 after conducting autopsies on victims in Alexandria, Egypt, and Calcutta, India.1 Cholera, whose name comes from

choler

or yellow bile, the humor often associated with digestive illnesses, made its impact not so much through its mortality as through its especially dramatic symptoms. In Europe, Russia, and the United States, death rates from cholera probably never exceeded 2 to 3 percent, although they were considerably higher in other parts of the world, particularly India and Southeast Asia, North Africa, the Caribbean, and South America, where they could reach 10 to 15 percent.2 Nonetheless, cholera was feared even in Europe as almost a second Black Death, largely due to the terribly sudden onset of some truly horrific symptoms, which include uncontrollable defecation and vomiting, painful muscle spasms, and an alarming bluish tinge to the skin (hence the name “blue death”) and gaunt appearance to the face. All this is the result of rapid dehydra-tion caused by a toxin released by the bacteria that reverses the osmosis process through the lining of the small intestines, creating the salty fluid on which the bacteria thrive. Although

Vibrio cholerae

is normally destroyed by acids and enzymes in the stomach and even in saliva, making the disease hard to contract, some of the bacteria if ingested in sufficient numbers will reach the intestines, where their assault starts peeling away the lining, resulting in “rice-water” stools.

The disease is then passed on to other victims typically when sewage containing contaminated feces seeps into a population’s untreated drinking water, although 101

102 y Chapter 4

the bacteria can also be transmitted and live for days or even weeks in contaminated food. Complete prostration due to a sudden drop in blood pressure and shock can occur within hours, so that it was said a man healthy in the morning could be dead by evening, or a person could simply collapse in the street lying in his own excrement. (Roughly half of all victims afflicted by the disease died.)3

Cholera was therefore a particularly humiliating, not to say agonizing and terrifying, disease to die from by the standards of nineteenth-century sensibilities, which presented quite a contrast to the romantic associations with the “easeful death” of tuberculosis. Only bubonic plague and smallpox could probably equal or surpass it in terms of the terror the spectacle of its symptoms could inspire.

Cholera has been a worldwide phenomenon but is said to have its endemic home in India, more specifically the Bengal region, where nearly every pandemic seems to have originated. (This is why the disease is sometimes known as

Asiatic cholera.) Historians count seven separate pandemics of cholera to have occurred throughout history, the first beginning in 1817 in Bengal, India; earlier occurrences of the disease no doubt existed, although it is hard to distinguish these in the record from other gastrointestinal diseases, such as dysentery or diarrhea. Last-ing until 1824, the first pandemic was largely confined to India, Southeast Asia, China, Japan, the Middle East, and southern Russia. It was not until the second cholera pandemic of 1827 to 1835 that the disease directly impinged itself upon the consciousness of Europe and the United States, particularly in the crucial year of 1832. The third pandemic from 1839 to 1856 brought the disease for the first time to South America, especially Brazil, and to much of North Africa as far west as Tunis. During the fourth pandemic of 1863 to 1875, much of sub-Saharan Africa was ensnared in cholera’s worldwide net. By the time of the fifth and sixth pandemics of 1881–1896 and 1899–1923, greater understanding of the disease largely confined its worst mortalities to the east, including Egypt and the Arabian peninsula, Persia, India, and the Philippines, although some notable epidemics did occur in Europe and Russia, including an outbreak in Hamburg, Germany, in 1892 and in Naples, Italy, in 1910–1911. The seventh, and last, cholera pandemic first began in 1961 in Southeast Asia with the appearance of an alternative strain of the disease, named El Tor (after the quarantine camp in Egypt where it was first identified in 1905), and persists to the present day.4 As of 2007–2008, cholera has been reported in India, Iraq, Vietnam, and throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa. Recent epidemics of cholera, however, are characterized by much lower infection and mortality rates than in the past, but the disease is persistent and endemic in some parts of the third world largely because of poor sanitation and poor access to safe drinking water supplies.5

Cholera, like tuberculosis, lends itself particularly well to a social interpretation of disease. What exactly that interpretation should be, however, has been Cholera y 103

much debated by historians. Traditionally, cholera has been seen as dividing nineteenth-century European society into two camps, those who preferred to explain it as the product of person-to-person contagion and those who saw it as caused primarily by environmental factors, such as miasma, poverty, filth, and so on. Each explanation in turn produced its respective champions in terms of how best to combat cholera. Contagionism, typically associated with conservative members of the ruling class, advocated quarantine, while anticontagionism, also referred to as localism or infectionism, which was taken up by bourgeois captains of commerce and political liberals and free traders, recommended sanitation measures and better hygiene. Both had their antecedents in Europe’s medieval and Early Modern past during the fight against plague. In reality, as more recent historians have argued, etiologic approaches to cholera did not always fall so neatly along these lines; often, in fact, the two might blur together within the same explanatory system, which perhaps best reflects the true epidemiology of cholera, and became known as “contingent contagionism.”6

Nineteenth-century cholera also presents historians with an opportunity to study the possible connections between disease and social conflict. The epidemic in Europe during the 1830s in particular coincided with social upheavals, such as the aftermath of the 1830 July Revolution in Paris that overthrew the Bourbon monarchy of Charles X in favor of the Duke of Orleans, Louis Philippe. Antago-nisms between the social classes opened up by the revolution, which can be traced back even further to the French Revolution of the previous century, are believed to have been exacerbated by the sudden and unexpected arrival of cholera in the Paris capital in June 1832. Workers and populist elements tended to deny the existence of the disease or attribute it to a poisoning conspiracy on behalf of the government and ruling class; accusations of poisoning to explain disease of course go back to the medieval Black Death, but in the case of cholera it was particularly apropos since the observed gastrointestinal symptoms seemed to make it medically likely, and the recent economic theories of Thomas Malthus, which took a complacent attitude toward disease as a necessary check on population, seemed to supply a motive. This time, doctors became the main target of the mob’s scapegoating ire as potential agents of the government’s campaign to supposedly improve the “public health,” and rioters tended to congregate outside cholera hospitals. Meanwhile, bourgeois and upper-class elements might see the disease as an excuse for greater state intervention and control of their social inferiors, not only on the grounds that cholera could incite rioting and other threats to public order, but also because the very conditions of poverty and filth associated with the lower classes were viewed as an integral cause and essence of the disease and thus opposed to Enlightenment progress and civilization. This became of particular concern as cholera began spreading from the poor slums where it began to more 104 y Chapter 4