Poison (31 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

“I have to tell you, detective, I have concerns about an exhumation in India,” Cairns said.

He went through his list. It takes a small dose of strychnine to kill an infant, and those twins had been in the ground all this time—it’s an open question whether, if there ever had been poison in the babies, it would still be in the tissue.

Moreover, you have to identify the remains. If the graves were unmarked, you would need to match DNA from the remains with a parent to confirm the lineage. If Dr. Smith assisted, he would need to bring the bodies back to Canada to test them here, and the cooperation of the Indian authorities would be needed to do that. Cairns considered the endeavor a long shot. Korol handed his cellphone to Bentham.

“Brent, you should hear what Dr. Cairns has to say as well.”

Bentham listened, his mind processing each part of the equation before him. An exhumation is a huge undertaking, even in Ontario. There are approvals to obtain. There’s the cost involved. It’s a big gamble. Even more so in India. Did they ever do exhumations at all there? Would they allow Canadians to come in and do it? Bentham was a careful man. Would he put the brakes on the enterprise?

“Hey, Brent, if you don’t shoot you don’t score.” Korol grinned at Bentham, a hockey fan who played pickup each week.

The assistant Crown attorney was on board. They all were. Starting the legal machinery of treaty assistance with India and returning to India to continue the investigation would be expensive and time-consuming. But they were chasing a serial killer and had gone too far to back off now. Time was running out on the decomposing remains of the twins. The only thing they knew for certain was that they would never really know whether the bodies contained strychnine if they didn’t examine them.

In June, Korol began regular communications with Sarvjit, Dhillon’s niece who was now 22 years old. She told Korol she had once asked Dhillon if he thought a man could kill his wife. Dhillon did not reply. Sarvjit cooperated with Korol. She began listening to her uncle’s telephone conversations and told Korol what was said. On

June 24, Korol received a page from Sarvjit. He called her back. She said that a friend of Dhillon’s in Toronto had advised him he should call Kevin Dhinsa’s home from a phone booth and say, “Dhinsa is dead.”

June 24, Korol received a page from Sarvjit. He called her back. She said that a friend of Dhillon’s in Toronto had advised him he should call Kevin Dhinsa’s home from a phone booth and say, “Dhinsa is dead.”

On June 23, Korol opened a letter from Dr. Michael McGuigan, the poison expert in Toronto. Korol had submitted copies of the witness statements gathered in India. “The description of Kushpreet’s death provides strong support for the implication of strychnine as the cause of death,” Dr. McGuigan’s letter read. As for the twins, “some aspects are consistent with strychnine deaths (i.e. crying, convulsions, stiffening or rigidity) while others are not (time course, vomiting). However, in the literature there are no reports of infants being poisoned by strychnine, so there are no reliable yardsticks for comparison. Based on the witness statements, strychnine poisoning is unlikely but it may well be worth disinterring the bodies.”

Korol forwarded the report on to Danielle Beaulne, a paralegal in Ottawa working on the documents for the exhumation. On June 30, Korol returned a call from Beaulne.

“Detective Korol,” Beaulne began, “Barb Kothe, the senior counsel here, is working on the Mutual Legal Assistance document. But she wants to know if, in light of the report from Dr. Michael McGuigan, you still want to travel to India?”

Korol didn’t blink.

“Actually, Danielle, Dr. McGuigan’s report is all the more reason to find out the cause of death of the children,” he said. “We know for a fact—and this is in a book we obtained in India—that milk, when ingested, can slow down the effects of strychnine poisoning, and witnesses said that people tried to give the children milk when they were ill. And some of the physical actions of the children were, in fact, consistent with strychnine poisoning. Tell Barb that Detective Dhinsa, Brent Bentham, and I all believe the babies should be exhumed.”

On July 2, Beaulne phoned Dhinsa. She was sending the finished treaty document to Pierre Carrier. Once the babies’ remains arrived in Ontario, she said, the investigators would need to deal with the proper officials here, which would mean obtaining a

coroner’s warrant to examine the remains. On July 29, Korol and Dhinsa drove to a hardware store and bought two plastic bins with lids. They were to carry the remains of Dhillon’s sons. Then they had two lockable aluminum boxes made, each big enough to hold one of the plastic bins. Dhinsa obtained ground-penetrating radar equipment. The equipment was state of the art. But not quite ready for India.

coroner’s warrant to examine the remains. On July 29, Korol and Dhinsa drove to a hardware store and bought two plastic bins with lids. They were to carry the remains of Dhillon’s sons. Then they had two lockable aluminum boxes made, each big enough to hold one of the plastic bins. Dhinsa obtained ground-penetrating radar equipment. The equipment was state of the art. But not quite ready for India.

CHAPTER 17

EXHUMATION

The jet touched down in New Delhi after four in the afternoon on Wednesday, August 13. Pierre Carrier spotted Dhinsa and Dr. Charles Smith lugging radar apparatus and the two containers. They all climbed into a High Commission van and left the airport. Carrier handed Dhinsa the signed Mutual Legal Assistance document—the license for him to investigate and dig up the remains in India. The next morning, a driver took them to Chandigarh, where Dhinsa once again shook the hand of Inspector Subhash Kundu.

The next morning Dhinsa, Smith, and Kundu left the hotel before dawn, drove four hours to Panj Grain. To Dhinsa, every hour now seemed precious. He had the documents issued by officials in New Delhi, but needed local approval to begin exhuming the bodies. So first they headed to the district administrative center, Faridkot, and visited the local magistrate, Som Prakesh. He sent them to a district prosecutor named Verma. An assistant led them into Verma’s office, which was dominated by an enormous desk—a status symbol in India. Verma entered the room and sat grandly behind the desk.

“First, we have tea,” he said.

Dhinsa continued in Punjabi.

“I need a warrant to proceed with the exhumation.”

“You’re a police officer, just do it,” Verma said.

“I can’t. I’m not a police officer in India.”

Verma pointed at Kundu.

“He is. He can do it.”

“No,” Dhinsa said, “we need judicial authority.”

“Well, you show me where the authority is and I’ll give you the warrant.”

Dhinsa sat in disbelief. You’re the district prosecutor. I’m a visiting police officer from Canada, and you want me to show you the authority? Verma’s assistant checked a reference book and said the authority for the warrant comes from the magistrate. Verma called Som Prakesh at home.

“Yes. I will give the authority,” Prakesh said. “Come back and see me tomorrow for the documents.”

Frustrated, they climbed back into their van and drove four hours back to Chandigarh. The next day, near Panj Grain, the magistrate presented them with a form to fill out so they could proceed with the exhumation. Finally, progress. “Complete this and bring it back tomorrow,” he added. No one was on hand to process the document the next day. It was August 15, the fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence. A national holiday. More red tape. Tomorrow, tomorrow. Dhinsa burned.

Before returning to Chandigarh, they stopped at Panj Grain. Smith wanted to see the graves. They parked at the cemetery gates, walked up the narrow path at the edge of the village to the burial ground. Smith looked beyond the walls, noticed the fields. He had been told they were wheat fields. But these were rice paddies. Soaked in water. Moist soil. The remains of the infants might well have decomposed to nothing! Smith turned to Dhinsa, ranting.

“We need dry sandy soil to preserve the remains. These are rice paddies! There will be nothing there.”

The van pulled up to the cemetery entrance. Smith and Dhinsa unloaded the ground-penetrating radar. Smith dragged a sensor along the dirt, searching for disturbances under the surface near the spot where witnesses said the babies were buried. He found one. A good sign.

The next day at 3 a.m. they were ready to return to the cemetary. In the rush to beat the traffic, with a long day’s work ahead, Dhinsa and Smith forgot to take their sandwiches and bottled water from the hotel kitchen. They arrived in Faridkot and picked up the warrant from the magistrate’s office then drove on to the cemetery. The magistrate sent a subordinate named D.S. Grewal and assigned two elders from the village to observe the operation. Smith and Dhinsa got out of their van in Panj Grain. It was only 7 a.m. but already the wall of heat and wet air were oppressive. It was the middle of summer, monsoon season. The heat and humidity was extraordinary; the sun’s rays beat on the men like a hammer.

Dhinsa and Smith unloaded the radar as a crowd gathered. Soon as there were more than a hundred, mostly children, encircling the cemetery, standing on the brick wall in bare feet, watching. Two police guards armed with rifles stood nearby. The

Punjabi police had sent them to protect the Canadians. There was also a handsome Sikh man in uniform, four stars gleaming on his epaulettes. He had studied at Cambridge, spoke English with a British accent.

Punjabi police had sent them to protect the Canadians. There was also a handsome Sikh man in uniform, four stars gleaming on his epaulettes. He had studied at Cambridge, spoke English with a British accent.

“The newspapers are aware that you are here. You are at risk,” he told Smith. Some weren’t pleased that Indian authorities had allowed the Canadians to chase Dhillon into his own back yard. Smith wiped the sweat from his forehead. Threats. The crowd. Clock ticking away on the remains. Unknown number of dead buried here. Rice paddies! Had he ever felt so much pressure?

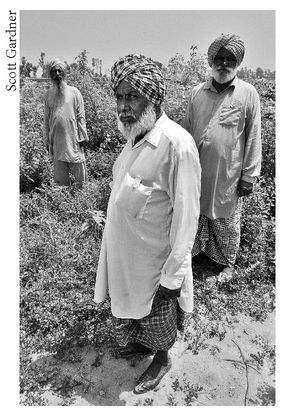

Sarabjit’s uncles, Bikhar Singh (left) and Biten Singh, in the cemetary

Exhumations, like autopsies, are a shock to those who do not know what to expect. The decayed human body is a sobering sight. The condition of a disinterred body varies, depending on time, the type of soil, and the climate. First the corpse turns gray and becomes shriveled. The flesh rots. In some instances, though, if the soil is moist, adipocere may form —a wax-like substance from body fats, that can delay putrefaction, so the features of the deceased are eerily preserved. Smith turned on the radar. It worked. And then stopped. It was the heat; by mid-morning it was so intense the machine couldn’t function. Once again it was up to family members who had been at the babies’ funerals almost two years earlier to point out the plots. Sarabjit’s father, the babies’ grandfather, walked to the spot at the far end of the rectangular cemetery, shuffled this way and that, and pointed at the ground.

“Here.”

Smith produced small tools that resembled dentist’s instruments. Villagers fetched shovels and picks. Smith started digging. Older farmers tried to take the tool from his hand.

“It’s okay, I am trained for this,” Smith said.

“We must help,” replied a farmer in Punjabi. “This happened in our village. It is our duty.”

As morning turned to afternoon, Smith and Dhinsa worked alongside the villagers, cutting through the fine layers of soil, each one a different color. Then they hit some brittle branches and thorns. An elder had put them there during the burials to keep wild dogs from digging up the bodies. Dhinsa took notes and videotaped the process. Warren Korol and Brent Bentham had stressed it: the exhumation and transportation of the remains had to be done with painstaking attention to detail, all of it documented. Smith and Dhinsa were kneeling on the ground now, scraping at the dirt with their bare hands, drenched in sweat, no water and no shade. Sixty-four centimeters down, they saw him. It was Gurwinder.

Other books

Dawn of Wonder (The Wakening Book 1) by Jonathan Renshaw

To Live in Peace by Rosemary Friedman

Heartlight by T.A. Barron

Jennifer's Gift (The Fantasy #2) by Ryan, Nicole

Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter by Mario Vargas Llosa

A Winter's Promise by Jeanette Gilge

Tyack & Frayne Mysteries 01 - Once Upon A Haunted Moor by Harper Fox

Fate and Ms. Fortune by Saralee Rosenberg