Pompeii (42 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

Meanwhile fantastic culinary creations caught the Roman imagination as much as they do the modern. At Trimalchio’s fictional banquet, a running joke is that none of the food is quite as it appears (rather like Trimalchio himself – an ex-slave pretending to be an aristocrat). One of the courses consisted of a boar, surrounded by piglets who turned out to be made of cake. When the boar was carved, a flock of thrushes flew out of its innards. A rather more mundane artifice, but with similar ‘deception’ in view, is recommended in Apicius’ cookery book. One memorable recipe is for ‘Casserole of anchovy without anchovy’. A mixture of any kind of fish, ‘sea nettles’ and eggs, it promises to pull the wool over the eyes of every diner: ‘at table no one will recognise what he’s eating.’

At Pompeii itself we find wall paintings depicting extravagant parties that fit nicely with our own modern stereotype of Roman dining. One scene (Plate 10) in the dining room in the Chaste Lovers bakery shows two couples reclining on couches covered with rugs and cushions. Though hardly a picture of sexual debauchery, other types of excess are on display. The drink is set out on a pair of tables nearby. A considerable quantity has already been consumed, for a third man has passed out on one of the couches, while a woman in the background has to be supported by her partner or slave. Another painting from the same room shows a similar scene, but this time in the open air, with the couches covered by awnings, and a slave mixing up the wine in a large bowl (wine was usually mixed with water in the ancient world).

In the House of the Triclinium, named for the paintings in its dining room, we find other variations on this theme. In one scene, a man who must just have arrived at the party is sitting on a couch, as a slave removes his shoes, while one of the other guests is already vomiting (Ill. 76). In another scene, in which entertainers perform for the guests on their couches, we glimpse a striking piece of furniture. What looks at first sight like a living waiter, is in fact a bronze statue of a young man, holding a tray for food and drink.

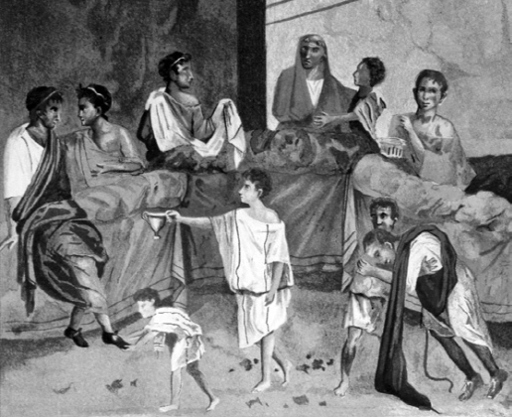

76. A nineteenth-century copy of a painting of a Roman party, from the House of the Triclinium. Notice how the servers, whether slaves or free, are shown as smaller than the guests. But they are very useful adjuncts to the occasion: one (on the left) removes a guest’s shoes; another (on the right), takes care of someone who is already being sick.

So do the dining rooms and dining customs of Pompeii match up to these images on its walls? In part, yes. We saw in Chapter 3 that, even for the city’s elite, formal dining of this type was probably restricted to special occasions, most food being taken on the run, sitting at tables, or perched in the peristyle. That said, some

triclinia

have been excavated which show an exquisite attention to detail and to luxury – as, for example, the dining installation overlooking the garden in the House of the Golden Bracelet, with its shining marble and babbling water (Ill. 35). The silver tableware and other elegant pieces of dining equipment occasionally discovered in and around Pompeii also conjure up an image of rich Roman dining, with all its stereotypes, jokes and cultural clichés.

In the House of the Menander, 118 pieces of silver plate, most of it dining ware, were found, carefully wrapped in cloth, stashed away in a wooden box in a cellar under the house’s private bath suite. Whether put here as the occupants fled, or more likely – as there was no sign of hurried packing – in storage during renovations to the house, this collection includes matching sets of drinking cups, plates, bowls and spoons (knives would have been made from tougher metal). There are even a pair of silver pepper or spice pots, in ‘Trimalchian’ disguise, one in the shape of a tiny

amphora

, the other in the shape of a perfume bottle.

A few miles outside the city, in a country house at Boscoreale, over a hundred silver pieces were unearthed at the end of the nineteenth century. These had almost certainly been hidden away for safe-keeping as the volcano erupted, in a deep wine vat where the body of a man – owner or maybe would-be robber – was also found. Among the precious service were a pair of cups which again strike a chord with Trimalchio’s banquet. In the middle of his feast a silver skeleton was brought onto the table, prompting Trimalchio to sing a dreadful ditty on the theme of ‘eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you die’ (a favourite topic of Roman popular moralising). Two of the silver drinking cups from Boscoreale are decorated with a jolly party – of skeletons (Ill. 77). Several are given the names of learned Greek philosophers, and are accompanied by suitable philosophical slogans: ‘Pleasure is the goal of life’ etc.

In some cases, we can point to an almost exact match between objects depicted in the paintings of drinking and dining on Pompeian walls and those found in the excavations of the city. The collection of silver plate shown on the walls of one rich tomb could almost be part of the dinner service from the House of the Menander. Even more striking is the free-standing bronze statue discovered in a large room in the House of Polybius (once a dining room, it was being used for storage or safe-keeping at the moment of the eruption). Imitating the distinctive ‘archaic’ style of Greek sculpture in the sixth century BCE, this figure holds its arms out, presumably to carry a tray. Though it is often assumed that this tray would have held lamps, making the statue an elaborate and expensive lamp-stand, it could equally well have been a ‘dumb-waiter’, holding food just as in the painting from the House of the Triclinium. That idea is certainly seen on a smaller scale in a group of table settings from another house in the city: four elderly men, naked, with long dangling penises, each supporting a small tray, for holding appetisers, titbits or any dainty food (Plate 12). Part of this design has had a surprising afterlife: overlooking the dangling penises, a well-known Italian kitchenware company is now marketing an expensive mock-up of this very tray.

77. A clever message for a rich dinner party. This silver cup from Boscoreale features some jolly skeletons, with moral slogans inscribed next to them.

But there are reasons for thinking that even on the grandest occasions, the reality of Pompeian dining would have been rather different from the images that surrounded it, and a good deal less sumptuous or elegant. The paintings on the walls, in other words, might have reflected an ideal of dining (vomiting and all) rather than the reality. Of course, the hard stone of the fixed couches would have been made much more comfortable and attractive by the addition of rugs and cushions. And no doubt, with practice, the idea of eating with your right hand, while leaning – semi-recumbent – on your left elbow would have come to seem entirely natural. All the same, many of the Pompeian dining rooms, where the couches still survive, seem with a practical eye to be awkward and cramped for the diners. Even in the top-of-the-range installation in the House of the Golden Bracelet, simply mounting the couches looks as if it could have been a difficult operation, at least for the less nimble. Some wooden steps, or their human equivalent in the shape of slaves, would have helped, but not entirely solved the problem. Besides, three people on these couches would feel to us rather crowded. Maybe in fact it did to the Pompeians too. The fact that the different utensils in the silver dinner services are arranged in pairs rather than threes may hint that the canonical ‘three on a couch’ was not always the practice in real life.

The details of the serving arrangements are also puzzling. Movable couches in a large display room would allow for flexibility and plenty of space. Not so the ‘built-in’

triclinia

. Where there are fixed couches, there is also often a fixed table in the centre, on which the food and drink must have been placed. But it was not large and there would have been little room to spare after nine (or even six) plates and drinking cups were put there. That suggests that portable tables and slaves would have had an important role, but there is little room for these either – particularly since servers could not move

behind

the diners to replenish food and drink as in a modern restaurant. And what of those cases where, as in the House of the Golden Bracelet, the central table is a pool of water. Here the younger Pliny, who kept well clear of the eruption of Vesuvius when his uncle went to investigate, and lived to tell the tale, can perhaps point us in the right direction. In one of his letters, he describes a villa he owned in Tuscany. This included an elaborate garden, with a dining area at one end with a pool of water in front of it, filled by water spouts that gushed from the couches themselves. He explains that larger dishes were placed for the diners on the edge of the pool, but that smaller dishes and garnishes were set floating on the water. That may well have been the principle in the House of the Golden Bracelet. If so, it’s hard not to suspect that, however elegant the arrangement was in theory, some of the food, not to mention the guests, became rather damp.

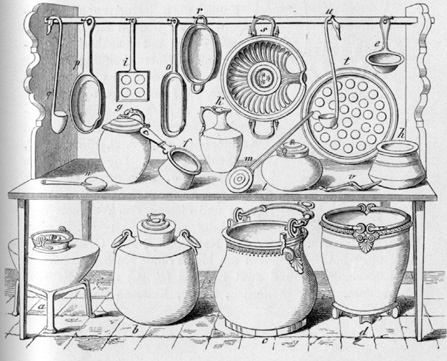

78. Pompeian cooking equipment, fit for a banquet. On the lower level, large buckets and vessels. Above, more sophisticated utensils – ladles, pans, moulds and what look like egg poachers.

This raises questions about the kind of food that would have been served in these fitted dining rooms. Influenced by Petronius, we tend to think of large elaborate dishes: whole boars with a stuffing of live birds being only one of many extravagant options. And it is true that some of the cooking equipment found at Pompeii suggests that some complicated confections were possible, even if not quite so showy as those offered by Trimalchio. Discoveries include plenty of large saucepans, frying pans, colanders, strainers and elaborate moulds for mousses (strikingly reminiscent of the shapes still used for modern jelly moulds: long-eared rabbits and fat pigs) (Ill. 78). Probably all that was feasible in a large room with movable couches. Not so in the smaller versions, however elegant. There the practicalities of space, and of eating with just one hand, prompts the suspicion that what was served was often simple and small, or at least already cut up into bite-size chunks. Against the lavish image of movie-style Roman banquets, we have to set an often more cramped and uncomfortable reality, with anything more substantial than the equivalent of a modern finger buffet making for awkward, messy eating.