Pox (6 page)

Authors: Michael Willrich

From the perspective of the patient, and the turn-of-the-century physician, the true horrorâand the real dangerâof smallpox resided on the outside of the body, in a rash so spectacular and explosive it was universally called “the eruption.” It was the eruption that ancient commentators had described, and that peoples around the globe had painted, with pointillist precision, on the images and figurines of smallpox sufferers. It was the eruption that had caused a medieval bishop to give the disease its Latin name,

variola

, meaning “spotted.” (In England, the disease was known simply as “the pox” until the late fifteenth century, when the term “smallpox” was adopted to distinguish it from syphilis, the “great pox,” or the French pox.) For physicians working at the turn of the twentieth century, it was still the eruption, above all else, that defined and signified smallpox.

37

variola

, meaning “spotted.” (In England, the disease was known simply as “the pox” until the late fifteenth century, when the term “smallpox” was adopted to distinguish it from syphilis, the “great pox,” or the French pox.) For physicians working at the turn of the twentieth century, it was still the eruption, above all else, that defined and signified smallpox.

37

The eruption appeared on the skin just as the fever broke, caused by the infection of the epidermal cells. The rash appeared first as small red dots (called macules) on the forehead and scalp, and often around the mouth and the wrists. Patients often got a “worried face,” a disturbing contraction of the facial muscles that some experienced doctors recognized as a diagnostic sign of smallpox. Within twenty-four hours the lesions spread over the body. They appeared so rapidly that even the most attentive patients found it difficult to track the order of their appearance. In the worst cases it would become difficult to distinguish the rash from the skin, but smallpox was, in its way, an orderly disease. It distributed itself in a characteristic centrifugal pattern that distinguished it from other skin diseases: it was most dense on the face, hands, and feet, though it also covered broad areas of the chest, back, trunk, arms, legs, and genitals.

38

38

Over the next two weeks, the lesions followed a well-known clinical course. Wyman's “Précis” ticked off the stages: “macule, papule, vesicle, and pustule, ending in desiccation and desquamation.” By the second day of the rash, a small raised bump (the papule) formed atop each red macule, rising just above the skin as the papule filled with fluid. Physicians described the papules as “shotty,” because they could be rolled between thumb and forefinger, as if shot from the blast of a hunter's gun had become embedded under the skin.

39

39

In a few more days, the papules evolved into vesicles, blisters with navellike depressions in their centers. (Physicians called the vesicles at this stage “umbilicated.”) The depressions gradually rounded out as the vesicles became filled with a pressurized fluid that started opalescent and gradually turned opaque. When that process was completed, after a few days, the lesions were called pustules. The puffy pustules had a yellowish gray color encircled by a red border. They reached their full size, like blood-engorged dog ticks, by the tenth day of the eruption. In the most common form of smallpox cases, the rash remained “discrete”: normal skin could still be seen between the lesions. But in more severe, “confluent” cases, there were so many pustules that they fused together, especially on the face. Dr. Long found it “almost impossible to paint a pen-picture” of the “terrible faces” of confluent patients.

40

40

Throughout the eruption, the patient suffered. As if to trumpet the ascendance of the pustules, the fever returned, as did many of the symptoms that had attended the fever the first time around. By this time, the patient's face was normally swollen and disfigured, the hands puffy and aching, the skin inflamed. Ulcers burned the mouth and throat, growing so large in some cases that the patient had the sensation of suffocating.

Stoner's

Handbook for the Ship's Medicine Chest

offered a concise description of the final clinical stages of smallpox, which occurred by the end of the eruption's second week. First came the desiccation: “The pustules break, matter oozes out, crusts form, first on the face and then over other parts of the body following the order of the appearance of the eruption.” The secondary fever gradually abated. Then came the desquamation, or scaling off: “The crusts rapidly dry and fall off, leaving red spots on the skin.” This could take two or more incredibly itchy weeks. Given the reigning scientific beliefs, all scabs and crusts had to be carefully collected and incinerated.

41

Handbook for the Ship's Medicine Chest

offered a concise description of the final clinical stages of smallpox, which occurred by the end of the eruption's second week. First came the desiccation: “The pustules break, matter oozes out, crusts form, first on the face and then over other parts of the body following the order of the appearance of the eruption.” The secondary fever gradually abated. Then came the desquamation, or scaling off: “The crusts rapidly dry and fall off, leaving red spots on the skin.” This could take two or more incredibly itchy weeks. Given the reigning scientific beliefs, all scabs and crusts had to be carefully collected and incinerated.

41

From the onset of fever to the separation of the scabs, smallpox typically lasted three to four weeksâthough sometimes much longer. Throughout, there was not much an attending nurse or physician could do but try to ease the suffering. “As regards treatment, there is little to say,” wrote Dr. Long. Cold compresses and cool drinks for the fevers. Morphine for the back pain. Vaseline ointments for the exfoliating scabs. A few ounces of whiskey sometimes bought the patient a moment's peace. Dr. Llewellyn Eliot, who ran the District of Columbia Smallpox Hospital during the winter epidemic of 1894â5, said he tried every treatment regimen he could think of: “the expectant, the bitartrate of potash, the salicylic acid, the antiseptic, and, finally, the do-nothing.” Still, good nursing care could make all the difference. As late as the 1970s, studies showed that in developing countries, where hospital facilities were typically “poor” and “grossly overcrowded” (a fair description of most American smallpox hospitals circa 1900), smallpox patients cared for by devoted family members, in their own homes and villages, had a higher chance of survival .

42

42

In a run-of-the-mill case of smallpox, as it had been known from time immemorial until the twentieth century, the sufferer had about a one-in-four chance of dying from the disease: a case-fatality rate, in epidemiological parlance, of 25 percent. Beneath this historical average lay wide variation, caused by differences in viral strains and the particular susceptibilities and immune responses of different individuals and groups. In cases of discrete smallpox, the case-fatality rate could be as low as 10 percent; in confluent cases, it could run to 60 percent or higher. Age also affected the prognosis. Mortality was highest in infants, lowest for young children, and from there it tended to rise with age. Smallpox was especially severe in pregnant women. It often caused miscarriages or stillbirths, and fetuses could be infected in utero.

43

43

Some outbreaks were so sudden and severe as to defy comprehension. In March 1900, the

Atlanta Constitution

reported that the small community of Jonesville, Mississippi, was “honeycombed with smallpox of the most virulent and loathsome form.” The case-fatality rate was 75 percent. Nearly one hundred people died. Entire families perished. It all happened so fast that city officials could do little more than order coffins .

44

Atlanta Constitution

reported that the small community of Jonesville, Mississippi, was “honeycombed with smallpox of the most virulent and loathsome form.” The case-fatality rate was 75 percent. Nearly one hundred people died. Entire families perished. It all happened so fast that city officials could do little more than order coffins .

44

When death came, it usually occurred around the tenth or eleventh day of the disease. Scientists still do not know exactly how smallpox killed. By the tenth day, the variola bricks had piled up in cells throughout the body, including many of the vital organs. Still, the disease did not normally destroy the organs. The slow, painful death from smallpox was usually caused by severe viral toxemiaâa generalized poisoning of the body. In the final moments, most patients suffered respiratory failure.

45

45

It could be worse. Discrete and confluent smallpox were subtypes of “variola vera,” or true smallpox. (“Ordinary type” is the preferred term today.) In a small percentage of cases, smallpox presented in far more severe forms. If a particularly virulent strain of the virus met with an extremely weak immune response at the cellular level, as sometimes occurred in children, the lesions remained flat, turned black or purple, and were said to feel “soft and velvety to the touch.” The patient's body looked charred. This form of smallpox (now called “flat type”) was almost invariably fatal. Rarer still, and almost always fatal, were the various forms of “hemorrhagic” or “black smallpox,” in which the virus caused explosive bleeding. Through it all, patients suffering from hemorrhagic smallpox were said to exhibit “a peculiar state of apprehension and mental alertness.” They seemed to know exactly what was happening to them.

46

46

The best thing to be said about smallpox was this: when the disease was done with a person, it was done. The virions did not persist in the body. Smallpox survivors were forever immune. In most cases of variola vera, though, the skin never fully recovered. From 65 to 80 percent of patients bore deep scars on their faces, the pitted “pockmarks” that made smallpox unforgettable.

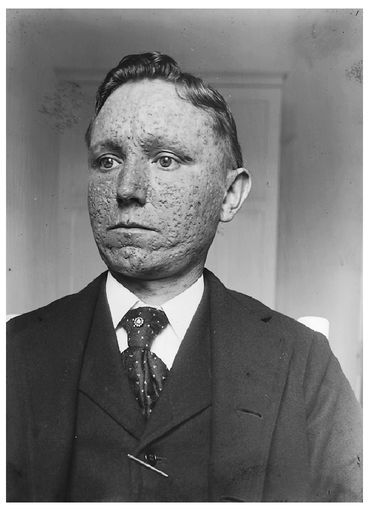

During the Cleveland smallpox epidemic of 1901â3, in which 266 people died, Dr. William T. Corlett, a professor of dermatology and syphilology at Western Reserve University medical school, kept a photographic record of patients in the smallpox hospital. After poring over Dr. Corlett's photos of patientsâtheir cobblestoned faces, their blistered nakedness, the distant stares of those who can open their eyesâit should come as a relief to find one of a fully recovered man. It does not. He could be thirty. Or forty-five. He wears a heavy woolen suit, with a gold watch pin at the top buttonhole of his vest. He stands erect, chin up, his body squared off to the camera. But his face is just a few degrees askew, as if he can't quite look the camera in the eye. His forehead, cheeks, nose, and chin are a dermatological rubble. The survivor's proud, clamped mouth carries the weight of the photograph. But the unforgiving eyes command the viewer's attention.

47

47

The scars of smallpox might fade with time, but they never went away. In the patent medicine marketplace of early twentieth-century America, unscrupulous purveyors touted newfangled procedures and ointments which, they promised, would make pockmarks disappear. In the same newspapers where the patent hucksters hawked their wares, the police blotters printed notices about wanted criminals. On any given day, the reader might be advised to keep an eye out for any number of physical markers in the hustle of the urban crowdâone suspect's height, another's build, yet another's race. But one trait in particularâthe smallpox marks tattooed indelibly on the suspect's faceâtold the vigilant reader that the fugitive had a history of escaping tight situations.

48

48

Dr. William T. Corlett of Cleveland's Western Reserve University took this photograph of a recovered smallpox patient. The scars were permanent.

COURTESY OF THE DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY

COURTESY OF THE DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY

Â

N

ot all “germs” are alike. Bacteria, which are much larger than viruses, are single-celled microorganisms, capable of reproducing on their own and metabolizing nutrition. Since the advent of penicillin in the 1940s, scientists and pharmaceutical companies have developed a widening range of antibiotics that work by killing or inhibiting the life-sustaining activities of various disease-causing microorganisms. Viruses are impervious to antibiotics. They are difficult to kill because they are not exactly alive. A virion is essentially an inert package of genetic information, encased in proteins. It can only replicate when it penetrates a vulnerable host cell. At that point, the virion sheds some of its protective layer and begins to convert the cell into a virion factory. The best way to help a human body beat a virus like variola is to teach the cells to recognize the virions and to respond quickly with a powerful immune response. For some viral diseases physicians artificially immunize patients by exposing their bodies to an inactivated (“killed”) or attenuated (“live” but weakened) form of the virus; for other diseases, a related virus does the trick. When preventive immunization works, the body reacts to an invasion of virus with an immune response that will prevent infection, or at least reduce the damage the virions can do.

ot all “germs” are alike. Bacteria, which are much larger than viruses, are single-celled microorganisms, capable of reproducing on their own and metabolizing nutrition. Since the advent of penicillin in the 1940s, scientists and pharmaceutical companies have developed a widening range of antibiotics that work by killing or inhibiting the life-sustaining activities of various disease-causing microorganisms. Viruses are impervious to antibiotics. They are difficult to kill because they are not exactly alive. A virion is essentially an inert package of genetic information, encased in proteins. It can only replicate when it penetrates a vulnerable host cell. At that point, the virion sheds some of its protective layer and begins to convert the cell into a virion factory. The best way to help a human body beat a virus like variola is to teach the cells to recognize the virions and to respond quickly with a powerful immune response. For some viral diseases physicians artificially immunize patients by exposing their bodies to an inactivated (“killed”) or attenuated (“live” but weakened) form of the virus; for other diseases, a related virus does the trick. When preventive immunization works, the body reacts to an invasion of virus with an immune response that will prevent infection, or at least reduce the damage the virions can do.

We know all of this because of the exponential growth of scientific knowledge that has occurred since the introduction of the germ theory of disease during the second half of the nineteenth century. In the 1860s and 1870s, laboratory pioneers such as the French chemist Louis Pasteur and the German physician Robert Koch marshaled increasing evidence behind an idea that we now take for granted. Overthrowing long-held medical beliefs, the new theory proposed that contagious and infectious diseases arose neither from the grossly deficient “constitutions” of their sufferers nor from atmospheric “miasmas” arising from stagnant water; rather, specific diseases were caused by particular microorganisms. From the late 1870s into the early twentieth century, laboratory scientists identified one pathogenic “microbe” after another (including the bacteria that caused cholera, consumption, gonorrhea, and typhoid). As scientific knowledge of bacteria, viruses, and other “germs” accumulated, so did understanding of the mechanisms and pathways by which those germs circulated across populations: contaminated food and water, casual contacts, insect vectors, and so on. From these new understandings of the etiology of infectious diseases arose new strategies for policing them. To the ancient practices of isolation and quarantine were added antispitting ordinances, food and milk regulations, and a growing arsenal of vaccines, antitoxins, and serums. In the United States, where many physicians had been slow to embrace the germ theory (and laypeople had been slower still), health officials of the local, state, and federal governments approached the twentieth century with a greatly enlarged sense of their duties and powers.

49

49

Other books

Agatha Webb by Anna Katharine Green

The Runaway by Martina Cole

She Who Was No More by Pierre Boileau

The Strength of the Wolf by Douglas Valentine

The Secret Sinclair by Cathy Williams

Locked Out of Love by Mary K. Norris

The Last Season by Roy MacGregor

Daughter of the Reef by Coleman, Clare;

Hunt Through Napoleon's Web by Gabriel Hunt

Freed (Vampire King Book 3) by Kenya Wright