Pox (7 page)

Authors: Michael Willrich

The history of smallpox vaccination has a special but curious relationship to this scientific revolution. Smallpox was the granddaddy of infectious diseases: the deadliest scourge in recorded history and the one upon which the field of immunology was founded. Smallpox

variolation

(using live variola virus) and

vaccination

(using the live viruses of cowpox or vaccinia) were the oldest practices of preventive immunization. In fact, they were practiced long before the germ theory took shape. Both techniques had been developed without the benefit of microscopes and laboratory smears, through experiments based upon everyday observations about the disease. Pasteur himself saluted this lineage when he proposed, in 1881, that the term “vaccination” be universalized to apply to preventive inoculation with other infectious agents.

50

variolation

(using live variola virus) and

vaccination

(using the live viruses of cowpox or vaccinia) were the oldest practices of preventive immunization. In fact, they were practiced long before the germ theory took shape. Both techniques had been developed without the benefit of microscopes and laboratory smears, through experiments based upon everyday observations about the disease. Pasteur himself saluted this lineage when he proposed, in 1881, that the term “vaccination” be universalized to apply to preventive inoculation with other infectious agents.

50

Variolation was practiced in China and India as early as the tenth century. It probably originated in the commonplace observation that people with pockmarks never contracted smallpox. The practice entailed introducing a small amount of material from the pustules or scabs of a smallpox patient into the body of a healthy person. In China, the common method was nasal insufflation: scabs were ground into a fine powder and then snorted. In India, the pus material was inserted into the skin. Variolation normally produced a mild attack of smallpox, followed by long-lasting immunity. The practice spread far and wide from its Asian (and perhaps African) origins. By the early eighteenth century, variolation spread into Europe from the Balkans and from Turkey into England. Called “inoculating the smallpox” or simply “inoculation” by the English, it grew increasingly common in Britain and the coloniesâespecially when epidemics threatened. In the terrible Boston epidemic of 1720â21, Reverend Cotton Mather and Dr. Zabdiel Boylston caused a public firestorm by promoting inoculation. In 1777, as North American smallpox epidemics took more than 100,000 lives, General George Washington ordered the compulsory variolation of all new recruits into the Continental Army. The wide adoption of variolation during the eighteenth century is perhaps all the evidence one needs of the severity of smallpox, for the practice carried serious risks. The artificially induced attack was not always mild: as many as one in fifty died. Even worse, during the infection the inoculated person could infect others with full-blown smallpox.

51

51

Vaccination descended directly from variolation, and it came about in much the same way. In the late eighteenth century, it was a commonplace observation among the country people of smallpox-ridden parts of England and Europe that milk hands and milkmaids rarely had pockmarks. An English country doctor named Edward Jenner, who had himself suffered a harsh bout of smallpox following his childhood inoculation, had trouble persuading dairy workers to take the pox. The workers, Jenner later explained, had the “vague opinion” that they had been protected by their exposure to diseased cows. Some of the workers had pocklike ulcers on their hands, gotten by milking cows whose teats were broken out with cow-pox. From one such ulcer, on the hand of a milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes, Jenner extracted the pus that he inserted, just beneath the surface of the skin, on the arm of a young servant named James Phipps on May 14, 1796. Jenner later repeated the experiment on several other children. After several months, he inoculated the children with smallpox. In every case, it failed to take. The children's bodies resisted the variola virus. Vaccination, which takes its name from the Latin word for cow, was born. The new technique had neither of the limitations of variolation: it did not give people smallpox, and it did not cause them to spread it either.

52

52

When Jenner published his first results in a 1798 paper, his claims bred skepticism and controversy among medical men and laypeople. An English political cartoon from the period depicts a gaggle of country bumpkins lined up to get jabbed in the arm by the bewigged Dr. Jenner. The right half of the frame is a riotous scene filled with men and women who have already taken the vaccine. Horns, hooves, and entire cows spring forth from their arms, faces, and rear ends. The cartoon is titled, “Cow Pockâorâthe Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation!” Despite opposition, vaccination spread far and wide with remarkable speed. Jenner estimated that within three years, 100,000 people had been vaccinated in England. By that time, Professor Benjamin Waterhouse of Harvard University had brought vaccination to the United States.

53

53

More than half a century before the germ theory, then, the fundamentals of preventive immunization were in place. And yet at the turn of the twentieth century, smallpox remained full of mystery. The causative agent had not been identified, the process of human transmission was imperfectly understood, and the exact nature and biological effects of the vaccine strains in circulation were largely matters of conjecture and debate. What scientists and physicians could say for certain, based upon a century of medical experience, was that vaccination worked. Wyman's “Précis” summed up the medical consensus: “The most efficient means for preventing the spread of smallpox is by vaccination. The protection, provided the [vaccine] virus is pure, is believed to be as complete against contagion as is that of smallpox against a second attack.” Unlike a bout with actual smallpox, the authors cautioned, vaccination conferred only a temporary immunity, perhaps five years or more. Accordingly, the “Précis” advised that communities encourage revaccination, whenever smallpox became prevalent, to “continue this protection indefinitely.”

54

54

In the best scenario, vaccination prevented a person exposed to smallpox from getting the disease at all. Even when a previously vaccinated person did contract the disease, the vaccination accelerated the clinical course of smallpox, producing a milder form of the disease called “varioloid.” The patient remained infectious until recovered: “The most virulent form of smallpox may rise from exposure to varioloid,” the “Précis” warned. But fatalities were rare and pockmarks uncommon. Physicians found that if they vaccinated a person infected with smallpox during the first five or six days of the incubation period, the patient would normally suffer a mild case of the disease.

55

55

Â

Â

D

espite the power of this revolutionary scientific technology, England and America did not rush to embrace compulsion. Some European governments established compulsory vaccination of infants in the first decades of the early nineteenth century: Bavaria in 1807, Denmark in 1810, Norway in 1811, Bohemia and Russia in 1812, Sweden in 1816, and Hanover in 1821. But England, the birthplace of Jennerian vaccination, did not enact its first compulsory measure until 1853. It applied only to children.

56

Until the mid-nineteenth century, the thorny legal question regarding vaccination in the United States concerned the right of local communities to use tax money to provide free vaccination for the poor. Things began to shift after England adopted compulsion. In 1855, Massachusetts became the first American state to require public schoolchildren to get vaccinated. Between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the twentieth century, public officials and lawmakers gradually built a legal regime of compulsory vaccination in America. By the 1890s, that regime included federal inspection of immigrants at the nation's borders, some form of compulsory vaccination for public schoolchildren in most states, and general vaccination orders issued by county courts, city councils, and local boards of health during epidemics.

57

espite the power of this revolutionary scientific technology, England and America did not rush to embrace compulsion. Some European governments established compulsory vaccination of infants in the first decades of the early nineteenth century: Bavaria in 1807, Denmark in 1810, Norway in 1811, Bohemia and Russia in 1812, Sweden in 1816, and Hanover in 1821. But England, the birthplace of Jennerian vaccination, did not enact its first compulsory measure until 1853. It applied only to children.

56

Until the mid-nineteenth century, the thorny legal question regarding vaccination in the United States concerned the right of local communities to use tax money to provide free vaccination for the poor. Things began to shift after England adopted compulsion. In 1855, Massachusetts became the first American state to require public schoolchildren to get vaccinated. Between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the twentieth century, public officials and lawmakers gradually built a legal regime of compulsory vaccination in America. By the 1890s, that regime included federal inspection of immigrants at the nation's borders, some form of compulsory vaccination for public schoolchildren in most states, and general vaccination orders issued by county courts, city councils, and local boards of health during epidemics.

57

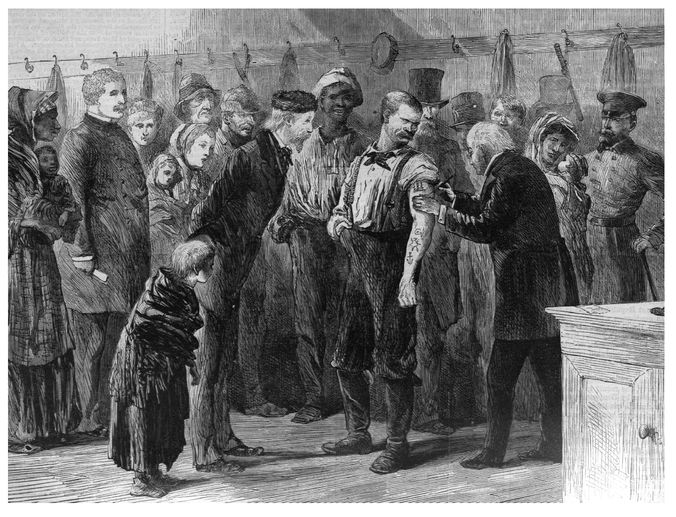

Sol Ettinge, “Vaccinating the Poor.” The engraving pictures a New York City police station house during the 1872 smallpox epidemic. From

Harper's Weekly

, March 16, 1872.

COURTESY ROBERT D. FARBER UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DEPARTMENT, BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY

Harper's Weekly

, March 16, 1872.

COURTESY ROBERT D. FARBER UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DEPARTMENT, BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY

Â

For Surgeon General Wyman, the case for compulsion was simple: it worked. He reminded Americans of the lesson of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870â71. As the French and Prussian armies collided, the war unleashed a pandemic of smallpox that killed more than half a million people in Europe, including some 143,000 German civilians. Both France and Prussia had poorly vaccinated civilian populations. But the armies differed dramatically. The thoroughly vaccinated Prussian army, 800,000 men strong, suffered only 8,463 cases of smallpox and just 457 deaths (a case-fatality rate of 5.4 percent). The smaller, sparsely vaccinated French army counted 125,000 cases and 23,375 deaths (18.7 percent). After the war, many European countries enacted new legislation compelling vaccination (and in some places subsequent revaccination) as a basic duty of citizenship.

58

58

As epidemics broke out in the United States during the next few years, American state and local governments responded with measures of their own. Again, the German example proved irresistible. By an 1874 law, the unified German state required all citizens to submit to vaccination and revaccination. In 1899 the disease took only 116 lives in Germany, a nation of 50 million people. For Wyman, the success of vaccination imposed a clear moral responsibility upon American citizens and their governments. “Smallpox is a disease so easily prevented by vaccination that the smallpox patient of to-day is scarcely deserving of sympathy,” he wrote in December 1899, as the wave of epidemics that had begun in the South moved across the country.

59

59

But vaccination carried its own well-known health risks, and compulsory measures clashed with medical beliefs, religious tenets, the rights of parents, and dearly held notions of personal liberty. As nations tightened their smallpox vaccination laws in the late nineteenth century, those efforts ran up against strong, even violent, antivaccination movements, in the metropoles and in their overseas colonies. Antivaccination riots rocked Leicester, Montreal, and Rio de Janeiro. Since the 1870s American antivaccination leagues had challenged compulsory measures in the statehouses; after 1890, they began turning to the courts as well. Across the United States, citizens resisted public health authority by burning down pesthouses built in their neighborhoods, running away from vaccinators, fighting with police, forging vaccination certificates, or, perhaps most commonly, by quietly taking care of their sick loved ones in their own homes, instead of surrendering them to the authorities.

60

60

American supporters of compulsory vaccinationâincluding public health officials, the rising professional class of physicians, and the editorial writers for major newspapers such as

The New York Times

âoften dismissed the opposition as an insignificant coterie of “imbecile cranks” who had fallen under the spell of foreign ideas. But the opposition was far more broad and complicated than that. It did not arise solely from a transatlantic critique of modern state medicine. Nor did it spring, fully formed, from American traditions of rugged individualism and constitutional liberty. The turn-of-the-century epidemics in particular would reveal that opposition to government-mandated smallpox vaccination grew up in the same soil from which had sprung compulsion itself: the conflict-laden realm of everyday social and political life in local communities.

61

The New York Times

âoften dismissed the opposition as an insignificant coterie of “imbecile cranks” who had fallen under the spell of foreign ideas. But the opposition was far more broad and complicated than that. It did not arise solely from a transatlantic critique of modern state medicine. Nor did it spring, fully formed, from American traditions of rugged individualism and constitutional liberty. The turn-of-the-century epidemics in particular would reveal that opposition to government-mandated smallpox vaccination grew up in the same soil from which had sprung compulsion itself: the conflict-laden realm of everyday social and political life in local communities.

61

The variola virus itself played no small role in the vaccination controversies that embroiled communities across the United States. As reports of outbreaks reached Washington from communities across the South during 1898 and 1899, many local physicians, public health officers, and political leaders commented that smallpox did not seem its old self. And the more people smallpox struck, the bigger the “kick” the public put up against vaccination.

62

62

Dr. Henry F. Long was one of the first southern medical men to report on this unprecedented new situation. Harvey Perkins had died as expected. But something peculiar happened to the sixty-two others who landed in Dr. Long's pesthouse during the months after Perkins made his long walk through the woods of Iredell County: every last one of them survived.

TWO

THE MILD TYPE

A peculiar new form of smallpox invaded communities across the American South during the last three years of the nineteenth century. The mysterious disease brought little of the horror people expected from smallpox. For every hundred people infected, only one or two died. Physicians and lay-people often mistook the symptoms for chicken pox, measles, or some other eruptive disease. The eruption passed through the normal stages, but the pustules typically remained superficial and discrete. Miraculously, most people recovered without pockmarks. At first the new pox reportedly spread almost exclusively among African Americans. Because of its unprecedented mildness and its reputation for infecting “none but negroes,” the new smallpox was allowed to gain a beachhead in the southeastern United States. Local governments were slow to respond until someone died or the disease crossed the color line. In this way, isolated cases became outbreaks, outbreaks became full-scale epidemics, and a disease whose ultimate capacity for destruction no one could foretell made its way from place to place.

1

1

Other books

The Silent Sounds of Chaos by Kristina Circelli

Blood Game by Iris Johansen

Bound by Blood (The Contract Book 3) by Steele, Suzanne

Conflicted: Keegan's Chronicles by Julia Crane

Sometimes It Happens by Barnholdt, Lauren

Frame-Up by John F. Dobbyn

The Broken Hearts Book Club by Lynsey James

The Bathrobe Knight by Charles Dean, Joshua Swayne

Apocalypsis 1.07 Vision by Giordano, Mario

Game Over! (Parker & Knight Book 3) by Wells, Donald