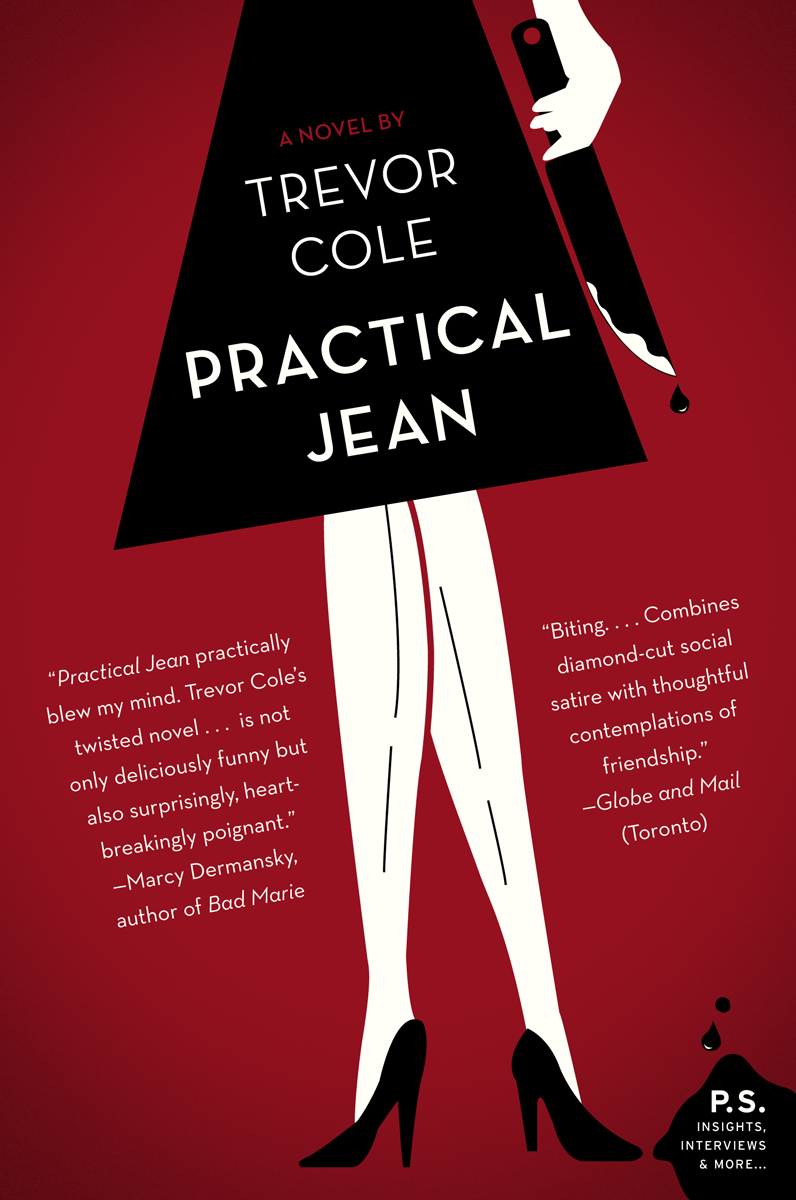

Practical Jean

Authors: Trevor Cole

Practical Jean

A Novel

Trevor Cole

For Hilda

Contents

YOU MIGHT THINK

this a rather horrible and depraved sort of story. But that's because you're a nice person. The events of this story are not the sort of thing that nice people think about, let alone do. But that's speaking generally, and traditionally, because the truth of it is that this story is filled with nice people, and yet what happened could not be more awful. It's one of the quirks of our modern times.

Everything began when Jean Vale Horemarsh had to look after her mother, Marjorie, who was dying of a terrible cancer in one of the soft organs. It might have been the pancreas or the liver. It wasn't uterus or lung or bone or breast. Jean never said exactly, but when she talked about her mother and how much pain she was in, Jean would move her hand around her middle, a bit off to the side. People watched that hand floating around there in the squishy mid-range, and most got the basic idea.

Just to meet her, you would have liked Jean. There's no doubt about that, because everybody liked Jean. She really was the most likeable person, always smiling, always looking you straight in the eye, asking about you and your children. Her favorite adjective was “sweet,” as in “Aren't you sweet?” and “Isn't that sweet?” And she liked the word “delectable,” too, when it came to describing an enjoyable food or situation. “That was a delectable party,” Jean would say. Charming, people called her.

You'll think, because of the past tense, that she's dead. She's not. It's just that now, most people in Kotemee keep their distance.

Pronounce that Ko-

teh

-me, by the way, please, not

Ko

-teh-me or Ko-teh-

meee

. A lot of day-trip visitors and TV reporters from the city get it wrong. Last May, Council almost voted to have the pronunciation added to the “Welcome to Kotemee” sign on Highway 18. But the motion lost by a two-vote margin. Some people don't adapt well to change.

Jean hadâhasâreddish blond hair, which she kept trimmed short because of her pottery and porcelain work, and that lovely pale, freckly skin that people with reddish hair often have. A lot of Hollywood actresses have that kind of skin and you'll only discover it when you see them in a really close-up picture in a magazine, but never in a movie because they cover it with makeup or make it disappear under hot lights. Which seems a shame. The other thing about Jean, physically, is that as she got older she struggled just a bit with her weight. You would never say that she was heavy, just heavier than she would have liked. But she was tall, about five-foot nine, so she carried it well. She had a nice, firm jaw line, and in public she made sure to wear little sweaters or linen jackets that gave her a good proportion. And when she stood talking to you, she would hold her arm casually across her stomach area, as if she were holding a glass of white wine, although usually there was nothing in her hand at all. It was just . . . there. You might have considered it an affectation, if you were being uncharitable.

Jean's mother was dying, then, of cancer, and Jean was taking care of her. While she did that, she lived at her parents' house on Blanchard Avenue, sleeping alone in one of the three guest rooms, which used to be her bedroom when she and her two brothers were children. It was quite a big house, with lovely olive-green clapboard siding, on one of the nicest streets in Kotemee, because Marjorie and her husband, Drew, had both been highly accomplished people.

Yes, accomplished is the word for Jean's parents. For most of her adult life, Marjorie Horemarsh was a veterinarian, and she looked so professional and dedicated in her white coat, with her auburn hair pinned tight, you would have gladly let her treat you for most any

human

trouble. And Jean's father, Drew, though he's been dead now for six years and retired for twelve before that, was the local police chief. His oldest son, Andrew Jr., went into the force as soon as he could and now he's the chief. There's no nepotism suggested; that's just how small towns work. Andrew Jr. took after Drew in lots of ways, including his size and his deliberate ambition, in this case to follow in his father's footsteps. “I'll be chief one day,” Andrew Jr. would say. “That's a lock.” And Drew didn't say any different. So everyone assumed that someday, Andrew Horemarsh, Jr., would be the chief of the twenty-three-man, five-car force, and for the last number of years he has been. And his brother, Welland, works with him in Community Services. Under him, technically, but most people in town say “with.”

Neither of the brothers could spare time away from their police work to help Jean take care of their mother in the last stages, which was no surprise. Marjorie could have afforded special care, but no, she considered it Jean's daughterly duty. And no visitors, either; Marjorie insisted on quiet. So there Jean was, alone, rambling about in the big house, attending to all the household and caregiving chores. She did it for three long, heartbreaking monthsâand she was able to do it, and it was expected of her, because she didn't work. Jean had what she herself called a passion, and some called a pastime, which, it was felt, she could put aside for the good of her family. Which was her ceramics. And now, get ready, because here comes the story of Jean's ceramics. Which is not the main story, only a side one. But it must be told.

Jean's ceramics, which she sold from a studio-showroom called Jean's Expressions, at the end of Kotemee's main street, were the loveliest, most ridiculous pieces of pottery you or any other living person has ever seen. She had an obsession with leaves, did Jean. For instance, if you were given a bouquet of flowers in a nice vase, and Jean came over, and you said, “Look at these lovely flowers that just came,” Jean would give you an “Aren't they sweet?” and she would barely even look at the flowers. She would go straight to the leaves. The greenery. Which is really the filler. She would let them lie against her palm in the light, looking at them with her head tilted at an angle and a dreamy haze over her face. And if it was a leaf she hadn't often seen, she would lean in close and study the veins and the cell structure and the edges, which she called the “margins.” And then she might sniff at the leaf, as if it had a fragrance.

And these leaves were what she tried to do in her ceramics. But she didn't simply paint leaves in pretty patterns on the usual plates and bowls and cups. No, she made the leavesâthe leaves themselvesâin various ceramic constructions, combined with tendrils and vines and ferns and shoots, the usual green elements. And her goal was to make these concoctions as lifelike and delicate and suspended in mid-air as the real thing. Which meant, as you would expect, they broke.

Half of the time they just shattered right in the kiln. And she would weep for every one. But if they survived that, then they broke as she moved them from the studio to the showroom. And if they endured that fourteen-foot journey, then they cracked or collapsed when someone bought one and tried to move it from the showroom to their car, or from the car to their house, or one day, a month later, when their teenager came home and slammed the door.

But Jean would not be deterred. She'd experiment with different clays, and glazes, and temperatures, because naturally people complained. When people buy a pottery cup, they want a good strong handle, and they expect that same kind of sturdiness in a ceramic anything. In their minds, that's the point of ceramics. But Jean's wish didn't seem to be to make something that would last; it was to make something exquisite, just to know that she had done it. She had always been like that, a different sort of thinker, an artistic spirit, you might say, ever since she was a child. And in a family of otherwise sensible, solid, down-to-earth sorts of people, real doers, as veterinarians and police officers are, that made Jean an anomaly. Her differentness bewildered her father and brothers, but it frustrated her mother deeply. So much so that whenever Jean, growing up, did or said something that was out of the sensible family normâglued hundreds of Swarovski crystals to her fingertips, say, or married a substitute high school English teacher named MiltâMarjorie would sigh and exclaim, “Little girl . . .” or “Young woman . . . how can you possibly be a Horemarsh? You don't have a practical gene in your body!”

When she was young, Jean didn't know about genes, so she thought her mother was ruing the lack of another sort of girl inside the body of her daughter. Another Jean . . . a practical Jean.

And then came her mother's long, painful, debilitating illness, when there was no use for the exquisite in the face of the dirty, dismal certainties. When she had to summon the practical in her. Until Marjorie Horemarsh finally, blessedly, died. And then what happened after that . . . happened.

And here in Kotemee, all anyone can say now is, “

Thank God

I was never a good friend of Jean Vale Horemarsh.”

T

he sun was shining on the whole of Kotemee. Spangles trembled on the lake, shafts of gleam stabbed off the chrome of cars lining Main Street, and in Corkin Park the members of the

Star-Lookout

Lions, Kotemee's Pee Wee League team, swung aluminum bats that scalded their tender, eleven-year-old hands. But for Jean Vale Horemarsh, there was no light in her life but the light of her fridge, and it showed her things she did not want to see.

A jar of strawberry jam, empty but for the grouting of candied berry at the bottom. A half tub of sour cream, its contents upholstered in a thick aquamarine mold. A pasta sauce and a soup, stalking fermentation in their plastic containers. A crumpled paper bag of wizened, weightless mushrooms. The jellified remains of cucumber and the pockmarked corpses of zucchini and bell pepper in the bottom crisper drawer.

In the kitchen of her sun-warmed house on Edgeworth Street, Jean bent to the task of removing each of these abominations. The jam jar was tossed into the recycling bin. The putrid liquids were dumped into the sink. The zucchini, cucumber, and mushrooms became compost. The mold-stiffened sour cream would not budge from its tub, so Jean scooped it out with her hand. Anything suspectâa bit of improperly wrapped steak, a bottle of cloudy dressingâwas presumed tainted and excised without mercy from the innards of the fridge. It was three o'clock in the afternoon and Jean still wore the black jacquard dress she'd worn to her mother's funeral. She had not found the will to take it off, although she had undone several of the buttons. So as she worked, erasing the evidence of time, destroying all signs of decay, her dress hung open slightly, exposing the skin of her back to the refrigerated air.

Watching her from a corner of the kitchen, Milt, Jean's husband, confessed that he should have cleaned out the fridge weeks ago, while Jean was still at her mother's. But it was a revolting chore, he said, and he kept putting it off; he didn't know how she did it.

“I have a strong stomach,” said Jean.

It had been three full months since Jean and Milt had lived together. Marjorie had made it clear that in dying she required Jean's full attention, which left Milt to mind himself at home. Now, as Jean bowed and stared into the cool, white recess, he came up behind her. He reached over her for a jar of peanut butter and, with only a slight hesitation, touched his fingers to the unbuttoned region of his wife's back and began to draw them lightly downward.

“What a terrible, terrible idea,” she said.

“Sorry.” He retreated with the peanut butter and screwed open the lid. “I just thought, we haven't . . . I think it was snowing the last time. But you're right, bad timing.” He set the jar and lid on the counter and reached for a bag of bread. “If you're hungry, I could make you some toast.”

Jean straightened at the fridge, summoned tolerance and forgiveness, and gave her husband a sad, sheepish look. She folded her arms around him and set her chin on his shoulder. It was more a lean than a hug. “Poor Milty,” she said. “Poor, poor Milty.”

“Milty's all right.”

“You can squeeze my breast if you want.”

“What, now?”

“Nothing's going to happen because of it. But you can do it if you like and then disappear into the bathroom or something.”

“Well, I don't think that's necessary.”

“Suit yourself.” She began to separate from him and before she did, he slipped a hand in and latched onto her left one, just holding it for a moment as she waited. “There,” she said finally, and patted his cheek as she left him.

“I could take it out right here,” he said from the kitchen.

“Don't.”

He headed past her, toward the powder room in the hall. “It's not like I haven't.”

A few minutes later, slumped on the matching green velour living room chairs in a room invaded by the late-afternoon sun, they stared at

Winter Leaves

, which Milt had set on the coffee table in honor of Jean's return. A clutch of hydrangea leaves ruined by frost it was meant to be.

“That looks nice there,” said Jean. “Thank you.”

“Thought you might like it.”

She pushed herself out of the soft cushions and leaned forward, squinting. “Is that a crack?”

“Just a small one. I glued it.”

“There's another one.”

“Only two, though. Don't keep looking.”

With a sigh Jean slumped back in her chair. “It is impossible for anything beautiful to last.”

“But you made something beautiful. That's the point.”

Jean stared at Milt. “That is the point, isn't it?”

“Absolutely.”

She nodded and let her chin rest on her chest. Never had she been so exhausted, and yet so relieved. The exhaustion and relief seeped through her muscles and bones, a bad and good feeling all at once.

This must be the way athletes feel

, Jean thought,

after they've run a thousand miles and won the game

. She let the sensation slip through her like one of those drugs that young people take and allowed her mind to drift backward to the funeral at First United Presbyterian. Everyone had been there: Jean's brothers, handsome so-and-so's in their dress uniforms; Andrew Jr.'s silent wife, Celeste, and their two grown children, Ross and Marlee, sparing four precious hours away from their busy young lives, thank you so much for your sacrifice; her own good friends, most of them anyway, full of sympathy and support; and a hundred Kotemee folk who'd known Marjorie Horemarsh as the best veterinarian they'd ever brought a sick spaniel to, and not as a mother who'd praised only marks and commendations and money and prizes and never beauty . . . never, ever beauty for its own sake, and not as a patient who moaned in pain seventeen hours a day and smelled like throw-up and needed to be bathed and fed and have her putrid bedsores swabbed and dressed . . .

“It was nice to see your friends there,” said Milt. “Louise looked good, I thought. Orâ”

“Louise looked good, did she?”

“Well. So did Dorothy. We should have them all over someday.”

Jean stared at the ceiling and sighed. “What's the point, Milt?”

“The house has been pretty quiet. You could play bridge, like you used to.”

“No, Milt, I'm not talking about that. I'm saying what's the point of anything?”

“Oh.” Milt tossed his head back against the chair cushion as if to say,

Wow, that's a big one

.

“Exactly,” said Jean. “You know, you think about a lot of things when you're taking care of your dying mother.”

Milt leaned forward in his chair. “Do you want a drink?” He rose and steadied himself. His tie was askew, and the end of it rested against the mound of his belly, a little like a dying leaf against a pumpkin, Jean considered.

“I will have some white wine.” She lifted her voice to talk as Milt made his way to the kitchen. “You think about things, Milt,” she said. “You ask yourself questions.”

“What sort of questions? No white, I'm afraid. Red?”

“Fine. Big questions, like, what's the point of anything?”

“Right.”

“You live, and then you die, Milt. And whatever you had is gone and it doesn't matter anymore. Nothing matters for ever and ever.”

“Wow,” said Milt on his way back with the glasses.

“So what is the point?”

He handed her the wine. “You want me to answer that?”

“I don't think you

can

answer that. I don't think anyone can.”

“I think the point is to live the best life possible, for as long as you're able.”

Jean, still sunk into the cushions and drugged with exhaustion, sipped her wine and picked at the threads of ideas and formulations and fantasies that had occupied her mind for the last couple of months, while she'd fed her mother unsweetened Pablum, while she'd stared at her thick, unweeded garden, while she'd kneeled alone in the en suite bathroom, cleaning the dried spray of urine from the floor where her mother had slipped.

“Beauty is the point, I think.”

“There you go. You answered it yourself.”

“A moment of beauty, or joy, something exquisite and pure.” She made a face. “I hate this red wine. Did you open it a week ago?”

“About that.”

“I'm not drinking it.” She set it on the coffee table. “That's it for bad wine.”

“Did you want me to drive and get some white?”

“Yes, but not now. Not while we're talking.” For a while she stared at the coffee table, at the wine yawing in the glass, at

Winter Leaves

, without really seeing any of them. “More than once, Milt,” she said. “More than once, when I was feeding Mom in bed? And she would lay her head back and fall asleep? I thought about pinching her nose and her lips closed and just holding them like that. Holding them tight.”

“Until she died?”

“Until she died.”

“Wow,” said Milt. His eyes went wide as he shook his head. He looked, Jean thought, as though he were really taking it in.

“Because what is the difference?” She shifted to the edge of the cushion. “Whether you die now or die later, it's the same thing, but one way has less suffering. They do it for animals. My own mother did it. I watched it happen.” Even now her mind filled with bright images, sudden whites and reds. In the very early days of her mother's career, when she'd had few clients and couldn't justify the cost of a clinic, Marjorie had used their kitchen table, spread with sheets of white plastic, to perform operations. She had allowed little Jean, who was the oldest of her children, to observeâthis was real life, she said, no need to hide itâas she sliced open neighborhood cats and dogs to pluck out their ovaries or spleens, or to reattach bloody tendons. Many times before she was seven Jean had watched her mother stick a hypodermic into the fur of some aged or diseased animal, watched her press the plunger and wait out the quiet seconds until its eyes closed. That was the simplest act of all, and the kindest, it now seemed to Jean.

“It's called âmercy,' Milt. That's what it's called. Don't let a living thing suffer. I should have done it. I hate myself for

not

doing it.”

“Don't hate yourself, Jean.”

Jean stared at

Winter Leaves

and lost herself in a scene that had come to her several times before, projected like a movie against the backs of her eyelids while she slumped in the chair in Marjorie's darkened room, listening to her mother breathe. She saw her hand reaching downâin her imagination it was always morning, daylight filled the room, and everything was a pale pinkâand squeezing her mother's soft nostrils between thumb and forefinger, the way you might seal the mouth of an inflated balloon. With the other hand she held her lips closed, too. Then the image changed, and she was pressing down on her mother's mouth; yes, that would work better. Squeezing her nostrils, and clamping down hard on her mouth. It wouldn't have been difficult; her mother was weak, and Jean's hands were muscled tools from years of working with clay. Marjorie's eyes would open, she'd be terrified, staring up at her daughter, fighting for her life, not realizing Jean's way was so much better. But it would only last a moment, that struggle, unlike the pain of her lingering disease. And afterward there'd be no recriminations, no feelings of betrayal, no abiding resentments. There'd be nothing, because that's what death was.

“I should have killed my mother, Milt.” Jean felt the tears puddling in her eyes. “I should have killed her before she got so sick. Then she wouldn't have had to suffer at all.”

He came to her and put his hand on her knee. “You were a good daughter to her, Jean. You took care of her.”

“Not like I should have.”

She reached into her sleeve for the tissue she'd tucked there and used it to dry her eyes. Though it was painful to believe that she had failed her mother by not taking her life, her conviction in that belief was, in an odd way, comforting. Certainty energized her. She took a deep breath and looked into Milt's sad, gray eyes. Such a sweet man.

“If you wanted to screw me,” she said to Milt, “I'd be game.”

Milt looked down at his hand on her knee, and off to the powder room. “I don't think I

can

now.”

She sighed. “That's annoying.”

“I can try.”

“No, never mind.” She patted his hand. “I'd be just as happy with some white wine.”