Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery, 2nd Edition (Ira Katz's Library) (34 page)

Authors: Garr Reynolds

A consequence of Zen practice is increased attentiveness to the present, a calmness, and an ability to focus on the here and now. However, for your average audience member, it is a safe bet that he or she is not completely “calm” or present in the “here and now.” Instead, your audience member is processing many emotional opinions and juggling several issues at the moment—both professional and personal—while doing his or her best to listen to you. We all struggle with this. It is virtually impossible for our audience to concentrate completely on what we are saying, even for shorter presentations. Many studies show that concentration really takes a hit after 15 to 20 minutes. My experience tells me it’s less than that. For example, CEOs have notoriously short attention spans while listening to a presentation. So the length of your presentation matters.

Every case is different, but generally, shorter is better. But why then do so many presenters go past their allotted time—or, worse, milk a presentation to stretch it out to the allotted time, even when it seems that the points have pretty much been made? This is probably a result of much of our formal education. I can still hear my college philosophy professor saying before the two-hour in-class written exam: “Remember, more is better.” As students, we grow up in an atmosphere that perpetuates the idea that a 20-page paper will likely get a higher grade than a 10-page paper, and a one-hour presentation with 25 presentation slides filled with 12-point lines of text shows more hard work than a 30-minute presentation with 50 highly visual slides. This old-school thinking does not take into account the creativity, intellect, and forethought that it takes to achieve a clarity of ideas. We take this “more is better” thinking with us into our professional lives.

The Japanese have a great expression concerning healthy eating habits:

hara hachi bu,

which means “eat until 80 percent full.” This is excellent advice, and it’s pretty easy to follow this principle in Japan since portions are generally much smaller than in places like the United States. Using chopsticks also makes it easier to avoid shoveling food in and encourages a bit slower pace.

This principle does not encourage wastefulness; it does not mean to leave 20 percent of your meal on the plate. (In fact, it is bad form to leave food on your plate.) In Japan and Asia in general, we usually order as a group and then take only what we need from the shared bounty. I have found—ironically, perhaps—that if I stop eating before getting full, I am more satisfied with the meal. I’m not sleepy after lunch or dinner, and I generally feel much better.

The principle of hara hachi bu also applies to the length of speeches, presentations, and even meetings. My advice is this: No matter how much time you are given, never ever go over your allotted time; in fact, finish a bit before your time is up. How long you talk will depend on your unique situation at the time, but try to shoot for 90 to 95 percent of your allotted time. No one will complain if you finish with a few minutes to spare. The problem with most presentations is that they are too long, not that they are too short.

Professional entertainers know that you want to end on a high note and leave the audience yearning for just a bit more from you. We want to leave our audiences satisfied—motivated, inspired, more knowledgeable—not feeling that they could have done with just a little less.

We can apply this spirit to the length and amount of material we put into presentations as well. Give them high quality—the highest you can—but do not give them so much quantity that you leave them with their heads spinning and guts aching.

This is a typical

ekiben

(a special boxed meal sold at train stations) from one of my trips to Tokyo. Simple. Appealing. Economic in scale. Nothing superfluous. Made with the “honorable passenger” in mind. After spending 20 or 30 minutes savoring the contents of the

ekiben

, complemented by Japanese beer, I’m left happy, nourished, and satisfied, but not full. I could eat more—another perhaps—but I do not need to. Indeed, I do not want to. I am satisfied with the experience. Eating to the point of becoming full would only destroy the quality of the experience I’m having.

Every word that is unnecessary only pours over the side of a brimming mind.

—Cicero

• You need solid content and logical structure, but you also have to make a connection with the audience. You must appeal to both the logical and the emotional sides of your audience members.

• If your content is worth talking about, then bring energy and passion to your delivery. Every situation is different, but there is never an excuse to be dull.

• Don’t hold back. If you have a passion for your topic, then let people know it.

• Make a strong start with PUNCH. Include content that is personal, unexpected, novel, challenging, or humorous to make a connection from the beginning.

• Project yourself well by dressing the part, moving with confidence and purpose, maintaining good eye contact, and speaking in a conversational style but with elevated energy.

• Try not to read a presentation or rely on notes.

• Remember the concept of

hara hachi bu.

It is better to leave your audience satisfied yet yearning for a bit more, than to leave them stuffed and feeling that they have had more than enough.

We say that the best presenters and public speakers are the ones who engage their audiences the most. We praise the best teachers for being able to engage their students. With or without multimedia, engagement is key. Yet if you ask a hundred people for a definition of engagement, you’ll get a hundred different answers. So what is engagement? For me, regardless of the topic, engagement is, at its core, about emotion. The need to appeal to people’s emotions is fundamental, yet often neglected. It’s about the emotions of the speaker and his or her ability to express those emotions in a sincere manner. But mostly, engagement is about tapping the emotions of the audience to get them involved on a personal level with the material, whatever it may be.

Like it or not, we are emotional beings. Logic is necessary, but rarely sufficient. We must appeal to people’s right brains, or creative sides, as well. Here’s what the authors of

Why Business People Speak Like Idiots

(Free Press) say:

“In business, our natural instincts are always left-brained. We create tight arguments and knock the audience into submission with facts, figures, historical graphs, and logic.... The bad news is that the barrage of facts often works against you. My facts against your experiences, emotions, and perceptual filters. Not a fair fight—facts will lose every time.”

We really have our work cut out for us. Our audiences bring their own emotions, experiences, biases, and perceptual filters that are no match for data and facts alone. We must be careful not to make the mistake of thinking that our data can speak for itself, no matter how convincing, obvious, or strong it may seem to us. We may indeed have the best product or solid research, but if we plan a dull, dispassionate, “death by slideument” snooze-fest, we will lose. The best presenters engage by tapping people’s emotions.

Reaching people at an emotional level can get attention, but it can also help your material be remembered. If you can arouse the emotions of your audience with a relevant story, an interesting (and relevant) activity, or a remarkable image or piece of data—for example, that is unexpected, surprising, sad, disturbing, and so on—your material will be better remembered. When a member of your audience experiences an emotionally charged event in your presentation, the amygdala in the limbic system of the brain releases dopamine into that person’s system. And dopamine, says

Brain Rules

author Dr. John Medina, “greatly helps with memory and information processing.”

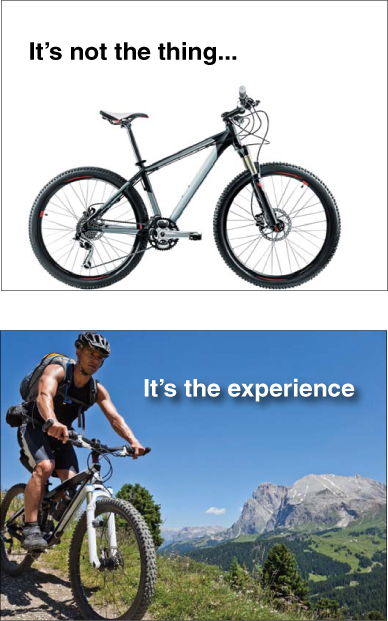

In a sales situation, for example, ask yourself what it is that you’re really selling. It’s not the features or the thing itself but the experience of the thing and all the emotions related to it that you are really selling. For example, if you were selling mountain bikes, would you focus on the features of mountain bikes or would you focus on the experience of using the bikes? Stories of experiences are vivid and visual and bring people’s emotions into your narrative.

A mirror neuron in the brain fires both when you do something and when you see someone else doing the same thing, even though you have not moved. It’s almost as if you, the observer, are actually engaging in the same behavior as the person who is engaged in the action. Watching something and doing something are not the same, of course, but as far as our brains are concerned, they’re pretty darn close.

Mirror neurons may be involved in empathy as well. This is a crucial survival skill. Research has shown that the same area of the brain that lights up when a person experiences an emotion also activates when that person merely sees someone else experiencing that emotion. When we see someone express passion, joy, concern, and the like, experts believe the mirror neurons send messages to the limbic region of the brain, the area associated with emotion. In a sense, then, there is a place in the brain that seems to be responsible for living in other people’s brains—that is, to feel what they are feeling.

I use the two slides above in a marketing presentation to remind people to think again about what it is they are really selling. Is it the thing or the experience of the thing? (Images in slides from iStockphoto.com.)

If we are wired to feel what others feel, is it any wonder that people get bored and disinterested when listening to someone who seems bored and disinterested, even though the content may be useful? Is it any wonder we feel stiff and uncomfortable while watching someone on stage barely move a muscle except for the muscles that make the mouth open and close? Too many presentations today are still given in an overly formal, static, and didactic style that removes the visual component, including the visual messages expressed through movement and displays of emotion. An animated, natural display of emotions enriches our narrative as it stimulates others to unconsciously feel what we feel. When you are passionate, for example, so long as it is perceived as genuine, most people will mirror that emotion back. Our data and our evidence matter, but the genuine emotions we project have a direct and strong influence—for good and for bad—on the message our audience ultimately receives and remembers.