Prime Time (48 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

Nursing homes need properly trained, properly paid caretakers who are rewarded for their hard work. Caretakers need opportunities for raises, continuing education, and career advancement. To address this issue, an ongoing grant initiated by the International Longevity Center allows care workers to take classes at twenty-four community colleges in multiple geographical locations as an opportunity to move ahead in the field of nursing. The purpose of the program is to allow care workers, who are often big-hearted but disenfranchised, to move toward a career that provides them with greater security and dignity. Many are not paid even minimum wage.

- We deserve properly paid, properly trained care workers.

- We deserve long-term-care facilities that uniformly meet federal guidelines.

Lost Opportunities in Research

We are losing ground in scientific research and medical training. Dr. Robert Butler has stated that although the United States is usually at the forefront of medical and scientific research, we now fall behind other countries in terms of the percentage of gross domestic product allocated for science. Over recent years there has been a 13 percent cut in science funding. This limits scientists’ ability to get grants, and many fine young PhDs who were trained in the United States are returning to their home countries.

- We deserve to see the world’s most advanced research programs on aging take place in the United States.

Furthermore, medical training in geriatrics is inadequate in our country. Only a fraction of our 150 medical schools have specific training programs in geriatrics. Medical students are sometimes offered elective courses on the needs of older patients, but these classes are pursued by only a small percentage of students. Worse yet, clinical medication trials rarely include older patients (the FDA does not require that the elderly be included in medication trials), even though older people use 40 percent of all the medications available.

- We deserve strong geriatric medicine programs in all of our nation’s medical schools.

- We deserve inclusion in medication trials.

Research on aging goes beyond the disciplines of biology and medicine. Dr. Laura Carstensen, founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity, believes that quality-of-life advancements require cross-disciplinary efforts. Social scientists need to continue to examine which factors contribute to health in old age, and psychologists should design campaigns for social change. City planners should assess what is necessary to help older people maintain active daily lives, with less time spent being sedentary. These are broad goals—but they are not impossible. A wider view of life-span wellness is required across all sectors of society. To make a true breakthrough in “longevity science,” a multitude of academics and professionals will need to dismiss the disease focus that currently defines old age.

- We deserve more research on healthy living across the life span.

A Revolution!

Some people think we are asking for a lot. Well, people at the forefront of revolutions do that. As we move toward unprecedented productivity and vitality through the life span, it is no time to lowball our demands. The longevity revolution requires us to raise public awareness so our contributions will be recognized and the reasonable supports we deserve will be put in place. Ultimately, aging is a universal experience that should unite our interests and efforts.

Let’s act—individually and together—to defeat ageism and apathy.

CHAPTER 20

Facing Mortality

Without an ever-present sense of death life is insipid. You might as well live on the whites of eggs.

—MURIEL SPARK

We do not know where death awaits us: so let us wait for it everywhere. To practice death is to practice freedom. A man who has learned how to die has unlearned how to be a slave.

—MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE

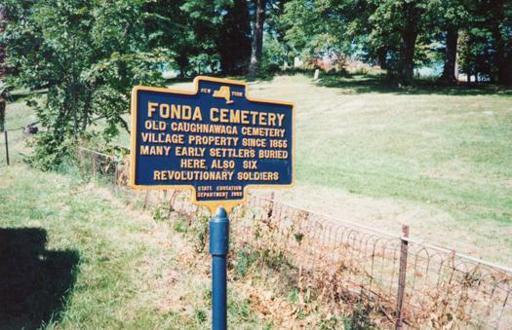

Fonda cemetery.

O

KAY, SO YOU THINK THIS IS MORBID AND YOU’D JUST AS SOON not read this chapter. Try for a minute to imagine what it would be like to live forever. There’d be no shape to life anymore, no meaning. What gives a thing meaning is the tension of its opposite: Silence means nothing without sound; light means nothing without darkness; even kindness without meanness or happiness without sadness turns mundane. After a while, after we’d done everything we wanted and needed to do, then what? Keep doing the same things forever? Same old, same old. There’d be no urgency, no incentive. When time is endless, moments lose their preciousness.

It’s not just old age that we rehearse for—that I’ve been rehearsing for over the last twenty-some years. I’ve been rehearsing for my death, as well. This may strike some people as gruesome, at least at first. In the 1970s, the singer Michael Jackson came to visit me in Santa Barbara. I pointed out to him a spot at the edge of a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean where I thought I might like to be buried, and I was stunned when he freaked out, screaming, “No! No!” It was incomprehensible and frightening to him that I could so easily accept my own death. Perhaps it was a blessing that he went out the way he did. I cannot imagine him living peacefully into old age.

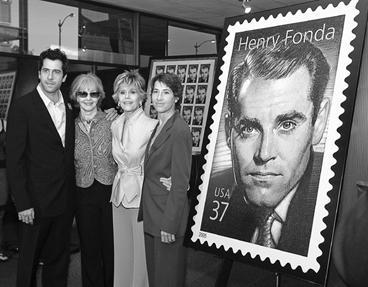

With my son, daughter, and stepmother, Shirlee Fonda, at the unveiling of the Henry Fonda postage stamp.

COURTESY OF THE UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE

Vanessa, Michael Jackson, me, and friends at the Michael Jackson Children’s Theatre, which he helped fund at my children’s camp.

From time to time I make an effort to imagine myself as very old. I see myself lying on a bed, frail and wrinkled. I can feel my soft little dog (alas, it probably won’t be my current dog!) curled under my arm. My children and grandchildren surround me. Most of my closest friends are younger than I am, and I see them there as well—coming and going as their lives permit. I know that what I want most is to see love in their faces. I know that I will have to live my life between now and then so as to deserve that love. I know that in order to be able to recognize their love and respond to it, I need to keep my mind alert. I know that in my dying I want to try to communicate my love for them, along with a sense of the appropriateness of death as a normal part of life. My friend Joan Halifax, a Zen priest who works with dying people, wrote that “we have an intuition that a fragment of eternity within us is liberated at the time of death.”

1

Joan also told me about her father. Two days before he died, a nurse approached him and asked, “How are you feeling, Mr. Halifax?” and he replied, “Everything!” I’d like to be able to say this right before my death:

I feel everything, the pure interconnectedness and interdependence of us all.

I know that to do so I will need to learn to have an open, accepting, love-filled heart, and that doesn’t just happen. It takes work.

I recognize my tendency to plan everything out according to my own vision, and I know that I mustn’t cling too possessively to this death narrative, because such things usually don’t work out as we’ve imagined. Still, the awareness of it helps me to live every day more fully.

During the writing of this book, I made a movie in France—in French—the first one after forty years in French! (Talk about a perfect brain workout and the activation of my higher-order cognitive functions!) One of the things that drew me to the movie was the way my character approaches her imminent death from colon cancer. She creates a lovely, vine-covered arbor, under which she intends to be buried; plants flowers; and plans on installing a bench next to her grave. (“I want to continue to receive guests,” she tells a friend, “and, besides, rows of headstones just aren’t my thing.”) There’s a scene I love where she tells the man who sells coffins that she doesn’t like the classical brown and black coffins and wants her casket to be pink. “You only die once,” she tells the salesman, “and I quite like the idea of surprising my guests the day of my burial.”

The truth is that none of us can know what kind of death we will have or when it will occur. All we know is that we are all terminal. It could come instantly or be long and painfully drawn out. I may not be able to communicate at all when the end comes. But I am learning about the growing practice of palliative care and the amazing people, like Joan Halifax, who are trained to be with the dying and bring them and their families comfort. I will want to know someone like this who can be present with me and my loved ones when my time comes.

I’ve had a talk with my children about how I want them to deal with my body when I die. I hope my passing won’t occur in a hospital, although for 80 percent of us in the United States that’s how it happens. If that’s where I end up, I want them to stand up to the nurses, take my body, clean it up, wrap it in a shroud, and put me into a hole at my ranch in New Mexico and cover me with earth. Simple as that. I want to be recycled, especially since I read somewhere that burials in America deposit 827,060 gallons of embalming fluid—formaldehyde, methanol, and ethanol—into the soil each year, and cremation pumps dioxins, hydrochloric acid, sulfur dioxide, and carbon dioxide into the air.

2

I’ve tried to live light on the planet. Why die heavy on it? I’ve told my children that I want a simple gravestone, though—something that my children and grandchildren can lay their heads beside. I like graves and headstones—always have. They give a tangible presence to the spiritual realm. I’m sad that Dad was cremated but never buried. Having a gravestone to sit by and touch would make it easier to feel as if I am with him.