Prohibition: Thirteen Years That Changed America (26 page)

Read Prohibition: Thirteen Years That Changed America Online

Authors: Edward Behr

“Big Bill” Thompson, mayor of Chicago during Prohibition years, and friend of gangsters. (National Archives)

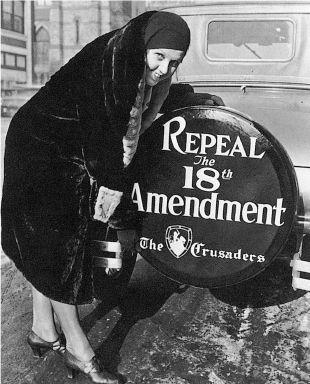

The beginning of the end: anti-Prohibition slogans on cars (1930–31). (

Library of Congress

)

Anti-Prohibition demonstration in New York in 1932. (National Archives)

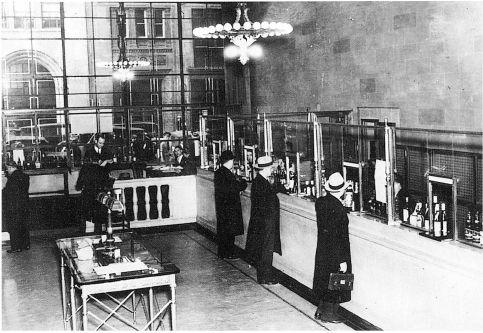

In 1933, but

before

the end of Prohibition, applicants for licenses to sell draft beer line up in New York.

(National Archives)

At Prohibition’s end, there were no liquor stores, and such was the thirst for legitimate liquor that some banks turned over their premises temporarily (1933).

(National Archives)

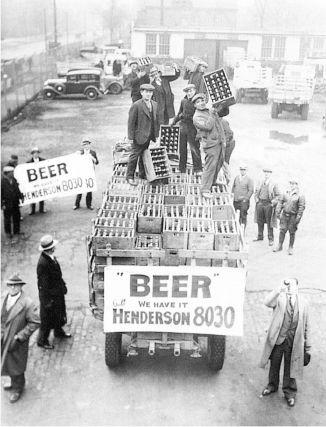

Happy workers celebrate the reopening of their brewery (1933). (National Archives)

In Philadelphia, a bar scene immediately after Prohibition’s end (1933). (National Archives)

Anyone who mingles freely with all classes of women is bound to discover very soon that the majority are opposed utterly and unalterably to reestablishment of open saloons. . . . Most women still lean economically upon men, their fathers or their husbands. Even if they have property they let men in the family handle it. The saloons deprived women not only of the companionship to which they thought they were entitled but absorbed money which the women felt they were entitled to share. For selfish reasons, quite as much as moral reasons, the women of the country will continue to cast their influence for prohibition. There is better furniture in the homes throughout the country than ever before, simply because a woman is able to divert a larger part of her husband’s income to household uses. There are more luxuries in which the family can share: automobiles, music lessons for the children and the like.

The modern girl, who makes no protest when her escort to dinner produces a pocket flask and shares its contents with her, has no present stake in prohibition enforcement. But the moment that girl marries, she probably will, whether consciously or not, become a supporter of prohibition, because she always will be unwilling to share any part of her husband’s income with either a bootlegger or a saloonkeeper operating legally. I am convinced that as far as the women of the country are concerned, prohibition has come to stay.

4

The arguments of Roy A. Haynes, the luckless Prohibition commissioner appointed by Harding on Wheeler’s recommendation (he too was part of the Ohio gang but one of the few honest ones), were far less convincing. Faced with an untenable situation, he was compelled to take an uncompromising moral stand: “It is no longer a question as to whether we are for or against that legislation, but whether we are for or against the United States Constitution.”

Haynes recognized that Prohibition was hideously difficult to police. The frontier between Canada and the United States was over a thousand miles long, and Detroit was a privileged entry point. No pursuit was possible on the river separating Canada from the United States in Detroit, for spy ships “financed by Canadian brewing interests” were on a permanent lookout for Coast Guard and Prohibition Bureau craft, and the “smugglers have to be caught in the act.” But his contention was that Prohibition was under control “and that control becomes more complete and more thorough every

day. . . . The clamor of a dwindling clique cannot drown the voice of truth.”

“The boottlegger’s life is increasingly one of fear, dread and apprehension,” Haynes claimed, with some truth. He failed to add that the financial rewards were such that the risks were worth taking, even if, as he noted, the bootleggers were constantly preyed on by politicians, public officials, police, and lawyers.

He was correct to say that “few men in any line or calling are subject to the temptation which besets the Prohibition enforcement agent.” Bribes

were

on a phenomenal scale. A group of brewers offered some agents a monthly $300,000 retainer to look the other way. The bootleggers, Haynes wrote, regarded the agent’s badge as “nothing but a license to make money. . . . Bootleggers brag of top political connections, with representatives in the Department of Justice, the Bureau of Internal Revenue and the Prohibition Unit itself.” In most cases, though Haynes did not say so, such accusations were well founded.

There were indeed a few untouchables in the Prohibition Bureau, as George Remus found out to his cost. Haynes devoted a chapter to thirty “fallen heroes,” agents shot and killed between 1920 and 1925, either in running gun battles, in ambushes, while searching for stills, or as a result of being lured to lonely and deserted places where they were gunned down in cold blood. These included some authentic heroes, but some “executions” involved the paying off of old scores — the price some Prohibition agents paid for failing to make good their promises to “look the other way.”

Haynes could not avoid the issue of corruption within his own Prohibition Bureau. There were, he admitted, “weak men, few in number,” who could not “withstand the strain of temptation placed in their way [by the bootleggers].” Invariably, Haynes wrote, Prohibition agents were advised that if they accepted bribes, they would simply be adhering to an almost official code of conduct, for “claims are made by rich and apparently influential cliques that they have connections by which they can control the action of the ‘higher-ups’ in the various government departments. These claims are groundless.”

They were not, as he well knew. According to Haynes, only forty-three Prohibition agents were convicted in the courts between 1920 and 1925, which proved that “The force was 99% honest. . . . Let our

enemies make the most of the fall of these forty-three unfortunates. I am thinking of the other 3,957 who kept the faith.”

According to Haynes, of the forty-two convicted, twenty-three were found guilty of offenses involving corruption, and eight of drunkenness; one committed murder; one had a false expense account and tried to influence a grand jury; one committed theft; and the remaining eight suffered small police-court cases. “Of real corruption, therefore, the ratio stands at about one half of one per cent,” Haynes claimed.

This was nonsense, even if Haynes was compelled to add that those caught “are, doubtless, but a fraction of those who are guilty,” for the Prohibition Bureau’s record was, on the whole, appalling. As records would later show, between 1920 and 1930, some 11,926 agents (out of a force of 17,816) were “separated without prejudice” because their criminal involvement could not be proved, and another 1,587 were “dismissed for cause,” that is, for offenses that could be proved but might not warrant sentencing, or that would involve costly, publicized trials.

The discrepancy between Prohibition agents’ low salaries and their life-styles was staggering — some of them even showing up for work in chauffeur-driven cars. Not just subordinate agents but senior Prohibition Bureau officials were involved in bootlegging activities. In Philadelphia in 1921, the local Prohibition director was shown to have been part of a plot to remove 700,000 gallons of whiskey (with a street value of $4 million) from government-bonded warehouses. Daugherty promptly ordered the upright local prosecuting attorney, T. Henry Walnut, who uncovered the conspiracy, to resign, and the case was dropped. And though it was reopened, thanks to Walnut’s behind-the-scenes doggedness, all accused were discharged: the evidence against them in possession of the Justice Department mysteriously disappeared.

There were sufficient cases of this type to trigger a response from Harding himself. In his State of the Union message in December of 1922, he referred to “conditions relating to enforcement which savor of a nationwide scandal.”

Even after 1925, when a major reorganization of the Prohibition Bureau took place under the auspices of retired general Lincoln C. Andrews, the situation hardly changed. Andrews eliminated state

barriers, and did his best to make the Prohibition Bureau a part of the Civil Service, but this failed to eliminate corruption, for the simple reason that three-quarters of the Prohibition Bureau’s staff failed to pass the necessary Civil Service test. By 1928, only two-thirds of the vacancies had been filled. In Pittsburgh, a congressman stood for reelection after serving a jail sentence for using his influence to allow 4,000 cases of whiskey to be released from bond into the hands of bootleggers. Not only was he reelected, but the ASL helped him win back his seat: he had always voted dry.