Prohibition: Thirteen Years That Changed America (23 page)

Read Prohibition: Thirteen Years That Changed America Online

Authors: Edward Behr

There were some spectacular successes. A huge rum-running vessel called the

Taboga

(which had changed its name to

Homestead

and sailed under a Costa Rican flag) surrendered at sea to two Coast Guard vessels after a running battle. It had 2,000 cases aboard — a major disappointment for the boarders, for it had enough storage space for 50,000 cases. In another case, a young Coast Guard lieutenant called Duke single-handedly boarded the

Economy

and forced its crew to surrender at revolver point. But at other times Coast Guard ships simply looked the other way as “black ships” steamed straight into New York, unloading liquor within spitting distance of Brooklyn Bridge. A black ship crew member recalled that “the wharf was full of carts and they had a gang there to unload us. All of the front street was blocked off. Cops were keeping everybody off the wharf.”

12

Former Coast Guard lieutenant Joseph Slovick (who retired in 1952, having signed up as a teenager in 1928) gave a vivid description of the hazards involved. “There was no radar then, and we never knew where the ships were going to be,”

13

he said.

Their ships were always faster than ours, and they had protection from the local community. There were spotters out there alerting

them. I remember once we were chasing a rum-running fishing vessel off Fire Island and I saw a man drop off and make for the shore. He was warning the people waiting for the consignment that they were being chased. It was a cat and mouse game, and the smugglers made great use of sandbars. We knew that within our Coast Guard station there were informers working for the bootleggers.

As seaman second class, Slovick earned $36 a month. To his knowledge, there were no black sheep among his crew mates, but there were plenty among customs officers.

11A lot of the time, when we had seized some liquor, we didn’t bring it into the Customs house during the daytime because we didn’t want any contact with the customs men. They wore great big brown overalls and they would stash bottles of liquor in them as they carried the stuff into their trucks, as many as they could — they would keep it for their own purposes, or to sell.

The Prohibition Department has made, and is making,

substantial progress.

— President Warren Harding, in a preface to

Roy A. Haynes’s book

Prohibition Inside Out,

1926

T

wenty months after Prohibition became effective, the Internal Revenue Bureau, as it was then called, reckoned that bootlegging had become a one billion dollar business, and a senior official urged the government to take steps to recover $32 million from bootleggers in excess profits taxes. Americans consumed 25 million gallons of illegal liquor in 1920, the Bureau claimed, noting that another 30 million gallons had been released to consumers for medicinal purposes by the new Prohibition Unit.

1

For all this disastrous beginning, Prohibition apologists felt they had good grounds for believing that the long-awaited millennium was at hand. Statistics could be made to prove that, at any rate in the first few years of its existence, Prohibition worked, was indeed spectacularly successful.

“Deaths from alcoholism took a terrific tumble in 1920,” wrote the

Literary Digest

, the best-informed, most influential American magazine of its day. Many years later, in occupied France, when

supplies of wine and hard liquor disappeared from the shops (all stocks had been requisitioned by the Germans), there was a marked drop in cases of delirium tremens, cirrhosis of the liver, and other alcohol-related illnesses — and this was also true of America, at least until the bootleggers got organized. State budgets all over the United States, in 1921 and 1922, reflected Prohibition’s impact. During those years, hospitals had fewer patients with alcohol-related illnesses; there were fewer cases of alcohol-related crimes, including street drunkenness; and there was a corresponding drop in the prison population. In Chicago, the DTs ward of Cook County Hospital was closed, as well as one wing of the Chicago City Jail.

Although Wheeler and the ASL naturally attributed the improvements exclusively to Prohibition, the Volstead Act alone was not responsible. In actual fact, as 1900-1910 statistics showed, per capita liquor consumption had steadily declined since the turn of the century, America had turned partially dry long before 1920, and in the 1917-1918 war years, many drinking American males were serving abroad.

Some health figures

were

impressive. In the years immediately before America’s entry into the First World War, the death rate from alcoholism had oscillated between 4.4 and 5.8 per 100,000 people. In 1917-1918 the drop was spectacular — from 5.2 to 2.7. To Prohibitionists, this was sufficient proof that America was indeed on the threshold of the much-vaunted millennium. In 1920, the death rate from alcoholism went down still further, from over 2 per 100,000 to 1. In 1921, there was a modest rise (1.8). In 1922, the level had climbed to 2.6 — still an improvement over the 1917 figure. In 1923, it climbed still further (to 3.2), and from then on the rise became vertiginous, even if deaths caused by adulterated liquor poisoning are excluded from the count.

As late as 1925, Wayne Wheeler could, with some legitimacy, argue that the benefits of Prohibition were huge — though some of his reasoning was specious. “Prohibition is decreasing crime,” the

Literary Digest

reported in January of 1925. Violent domestic crime

was down

, as were arrests for drunkenness and brawling. “Prohibition has saved a million lives,” Wheeler announced that year. “The welfare of little children is too eloquent a voice to be howled down,” the

Grand Rapids Herald

acknowledged.

Prohibition enthusiasts also used statistics to argue, again before

bootlegging operations got into their stride, that cash once spent on liquor was now being used to buy more and better food, and that consequently people were healthier. Statistics showed that grocery stores were doing better business, and that American families were putting more money into savings accounts.

“It makes me sorry we did not have Prohibition long ago,” wrote the editor-owner of the Seattle

Times

, who had originally opposed Prohibition. “Yes, sir, we have found in Seattle that it is better to buy shoes than booze.”

2

The Prohibitionists naturally claimed that the Volstead Act was uniquely responsible. This was by no means certain, for the revitalized postwar economy was almost certainly a likelier reason for the new spending patterns. In any case, benefits were only temporary, and long before 1929, such claims were no longer being made.

Wheeler declared that Prohibition had “doubled the number of investors” and was fueling America’s growing manufacturing boom — a “post hoc ergo propter hoc” argument, but one enthusiastically supported by most American industrialists, at least until the Great Crash of 1929.

One major but anonymous industrialist told Prohibition Commissioner Haynes that “before the Volstead Act, we had 10% absenteeism after pay day. Now it is not over 3%. The open saloon and the liquor traffic were the greatest curse to American morals, American citizenship, thrift, comfort and happiness that ever existed in the land.”

3

Men such as Rockefeller (at least at first) and Edison were also Prohibition supporters. And much was made of the fact that certain skilled labor unions, such as the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, had come out in favor of Prohibition.

Wheeler’s most vocal and influential Prohibition ally was undoubtedly Henry Ford — a major Anti-Saloon League contributor from the start. Ford’s rationale was simple: neither a principled nor a religious man (insofar as he had any moral convictions, these were based on the superiority of the white, Aryan race), his sole concern, as an innovative car manufacturer, was efficiency: hangovers slowed down the pace of the assembly line and provoked accidents. The Volstead Act did not make Henry Ford disband his private police, but their task became simpler, for they no longer had to keep watch over a multitude of saloons and liquor shops.

Halfway through Prohibition, Ford himself issued a stern warning in the

Pictorial Review

.

For myself, if booze ever comes back to the U.S. I am through with manufacturing. I would not be bothered with the problem of handling over 200,000 men and trying to pay them wages which the saloons would take away from them. I wouldn’t be interested in putting autos into the hands of a generation soggy with drink.

With booze in control we can count on only two or three effective days work a week in the factory — and that would destroy the short day and the five-day week which sober industry has introduced. When men were drunk two or three days a week, industry had to have a ten- or twelve-hour day and a seven-day week. With sobriety the working man can have an eight-hour day and a five-day week with the same or greater pay. ... I would not be able to build a car that will run 200,000 miles if booze were around, because I wouldn’t have accurate workmen. To make these machines requires that the men increase their skill.

Other automobile industry tycoons shared these views, and the Carnegie Institute’s tests on the effects of alcohol on human efficiency added credibility to Ford’s remarks. But the arguments in favor of Prohibition were not confined to industrialists. Some of the social arguments advanced no longer used the hysterical rhetoric favored by the ASL and the WCTU, which equated Prohibition with salvation. One of the few totally honest members of the Harding administration, Mabel Willebrandt, the deputy attorney general (and the infamous Daugherty’s “real” number two), argued that even if they drank in speakeasies, women were Prohibition’s greatest beneficiaries.

Herself one of America’s early feminists, who had defended prostitutes and victims of domestic abuse at the start of an impressive law career and had gone on to campaign for better conditions in women’s prisons — scandalizing some of her more straitlaced legal colleagues by becoming an early “Murphy Brown,” adopting a baby girl after her divorce — Willebrandt defended Prohibition in dispassionate, modern terms. She recognized that there was little interest in Prohibition “among those who congregate in country clubs and who have plenty of leisure and very little work.” Nevertheless, speaking as a woman in a male-dominated society, she wrote that

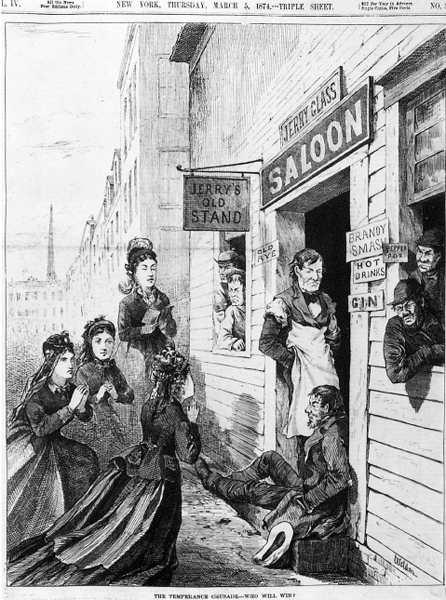

An early cartoon (1874) showing Women’s Christian Temperance Union volunteers picketing a saloon full of drunks.

(Library of Congress)

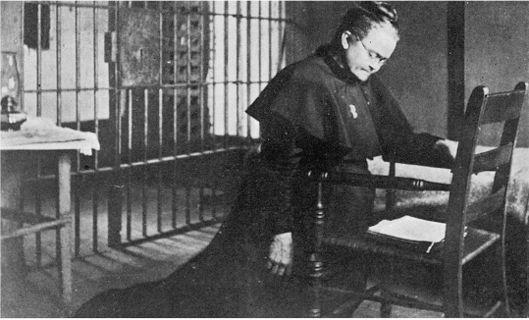

Carry Nation praying in her jail cell in Wichita, Kansas. (

Library of Congress

)