Puckoon (2 page)

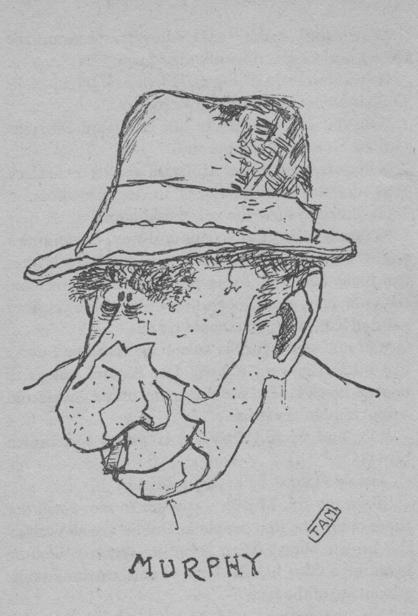

'I heeerd a crash,' said Murphy. 'I

examined meself, and I knew it wasn't me.'

' It was me,' said Milligan.' I

felled off me bi-cycle. Tank heaven the ground broke me fall.'

' Oh

yes,

it's very handy like dat,' said Murphy, settling his arms along the wall.

' Oh

dear,

dear!' said Milligan, getting to his feet.

' I've

scratched all the paint off the toe of me boot.'

' Is

dat right den, you paint yer boots ?'

' True

, it's the

most economical way. Sometimes I

paints

'em

brown,

when I had enough o' dat I paints 'em black again.

Dat way people tink you„got more than

one pair,

see ?

Once when I played the cricket I

painted 'em white, you should try dat.'

'Oh no,' said Murphy solemnly. 'Oh

no, I don't like inteferring wid nature. Der natural colour of boots is black

as God ordained, any udder colour and a man is askin' fer trouble.'

'Oh, and what I may ask is wrong wid

brown boots?'

' How

do I

know ? I never had a pair.'

' Take

my

tip, Murphy, you got to move wid der times man. The rich people in Dublin are

all wearin' the brown boots; when scientists spend a lifetime inventin' a thing

like the brown boots, we should take advantage of the fact.'

'No, thank you,' said Murphy's

eyebrows, 'I'll stick along wid the inventor of the black boots. After all they

don't show the dirt.'

'Dat's my argument, black don't show

the dirt,

brown

ones don't show the mud and a good

pair of green boots won't show the grass.'

'By Gor', you got something dere,'

said the Murphy.' But wait, when you was wearing dem white boots, what didn't

dey

show ?'

'They didn't show me feet,' said

Milligan, throwing himself on to the bike and crashing down on the other side.

' Caw

!' said

the crow.

'Balls!' said Milligan. 'I'll be on

me way.' He remounted and pedalled off.

'No, stay and have a little more

chat,' called Murphy across the widening gap.

' Parts

round here are lonely and sparse populated.'

'Well it's not for the want of you

tryin','

came

the fading reply.

The day brewed hotter now, it was

coming noon. The hedgerows hummed with small things that buzzed and bumbled in

the near heat. From the cool woods came

a babel

of

chirruping birds.

The greena-cious daisy-spattled

fields spread out before Milligan, the bayonets of grass shining bravely in the

sun, above him the sky was an exaltation of larks. Slowfully Milligan pedalled

on his way. Great billy boilers of perspiration were running down his knees

knose and kneck, the torrents ran down his shins into his boots where they

escaped through the lace holes as steam.

'Now,' thought the Milligan, 'why are

me legs goin' round and

round ?

eh ?

I don't tink it's me doin' it, in fact, if I had me way dey wouldn't be doin'

it at all. But dere

dey are

goin' round and round;

what den was der drivin' force behind dose legs? Me wife! That's what's drivin'

'em round and round, dat's the truth, dese legs are terrified of me wife,

terrified of bein' kicked in the soles of the feet again.' It was a disgrace

how a fine mind like his should be taken along by a pair of terrified legs. If only

his mind had a pair of legs of its own they'd be back at the cottage being

bronzed in the Celtic sun.

The Milligan had suffered from his

legs terribly.

During the war in

While his mind was

full of great heroisms under shell fire, his legs were carrying the idea, at

speed, in the opposite direction. The Battery Major had not understood.

'Gunner Milligan?

You have been acting like a coward.'

'No sir, not true. I'm a hero wid

coward's

legs,

I'm a hero from the waist up.'

' Silence

!

Why did you leave your

post ?'

' It

had

woodworm in it, sir, the roof of the trench was falling in.'

' Silence

!

You acted like a coward!'

' I

wasn't

acting sir!'

' I

could

have you shot!'

'Shot?

Why

didn't they shoot me in peacetime? I was still the same coward.'

' Men

like

you are a waste of time in war. Understand?'

' Oh

? Well

den! Men like you are a waste of time in peace.'

' Silence

when you speak to an officer,' shouted the Sgt. Major at Milligan's neck.

All his arguments were of no avail in

the face of military authority.

He was court martialled, surrounded

by clanking top brass who were not cowards and therefore biased.

' I

may be a

coward, I'm not denying dat sir,' Milligan told the prosecution. 'But you can't

really blame me for being a coward. If I am, then you might as well hold me

responsible for the shape of me nose, the colour of me hair and the size of me

feet.'

'Gunner Milligan,' Captain Martin

stroked a cavalry moustache on an infantry face. 'Gunner Milligan,' he said.

'Your personal evaluations of cowardice do not concern the court. To refresh

your memory I will read the precise military definition of the word.'

He took a book of King's Regulations,

opened a marked page and read 'Cowardice'. Here he paused and gave Milligan a

look.

He continued: ' Defection in the face

of the enemy.

Running away.'

' I

was not

running away sir, I was retreating.' 'The whole of your Regiment were

advancing, and you decided to

retreat ?'

' Isn't

dat

what you calls personal initiative ?' 'Your action might have caused your

comrades to panic and retreat.'

' Oh

, I see!

One man retreating is called running away, but a whole Regiment running away is

called a

retreat ?

I demand to be tried by cowards!'

A light, commissioned-ranks-only

laugh passed around the court.

But this was no laughing matter.

These lunatics could have him shot.

' Have

you

anything further to add ?' asked Captain Martin.

'Yes,' said Milligan.'

Plenty.

For one ting I had no desire to partake in dis war.

I was dragged in. I warned the Medical Officer, I told him I was a coward, and

he marked me A.i. for Active Service. I gave everyone fair warning! I told me

Battery Major before it started, I even wrote to Field Marshal Montgomery. Yes,

I warned everybody, and now you're all acting

surprised ?'

Even as Milligan spoke his mind,

three non-cowardly judges made a mental note of Guilty.

'Is that all?' queried Martin with

all the assurance of a conviction.

Milligan nodded. What was the

use ?

After all, if Albert Einstein stood for a thousand

years in front of fifty monkeys explaining the theory of relativity, at the

end, they'd still be just monkeys.

Anyhow it was all over now, but he

still had these cowardly legs which, he observed, were still going round and round.

'Oh dear, dis weather, I niver knowed it so hot.' It felt as though he could

have grabbed a handful of air and squeezed the sweat out of it. 'I wonder,' he

mused, 'how long can I go on losin' me body fluids at dis rate before I'm

struck down with the

dehydration ?

Ha ha! The answer

to me problems,' he said, gleefully drawing level with the front door of the

'Holy Drunkard' pub.

' Hello

!

Hi-lee, Ho-la, Hup-la!' he shouted through the letter box.

Upstairs, a window flew up like a gun

port, and a pig-of-a-face stuck itself out.

'What do you want, Milligan?' said

the pig-of-a-face. Milligan doffed his cap.

'Ah, Missis O'Toole, you're looking

more lovely

dan ever. Is there any chance of a cool libation

for a tirsty

traveller ?'

' Piss

off!'

said the lovely Mrs O'Toole.

'Oh what a witty tongue you have

today,' said Milligan, gallant in defeat. Well, he thought, you can fool some

of the people all the time and all the people some of the time, which is just

long enough to be President of the United States, and on that useless

profundity, Milligan himself pedalled on, himself, himself.

' Caw

!' said

a crow.

'Balls!'said

Milligan.

Father Patrick Rudden paused as he

trod the gravel path of the church drive. He ran his 'kerchief round the inside

of his holy clerical collar. Then he walked slowly to the grave of the late

Miss Griselda Strains and pontifically lowered his ecclesiastical rump on to

the worn slab, muttering a silent apology to the departed lady, but reflecting

,

it wouldn't be the first time she'd had a man on top of

her, least of all one who apologized as he did. He was a tall handsome man

touching fifty, but didn't appear to be speeding. His stiff white hair was

yellowed with frequent applications of anointment oil. The width of neck and

shoulder suggested a rugby player, the broken nose confirmed it.

Which shows how wrong you can be as he never played the game in his

life.

The clock in the church tower said 4.32, as it had done for three

hundred years. It was right once a day and that was better than no clock at

all. How old the church was no-one knew. It was, like Mary Brannigan's black

baby, a mystery. Written records went back to 1530. The only real clue was the

discovery of a dead skeleton under the ante-chapel. Archaeologists from

and

come

racing up in a lorry filled with little

digging men, instruments and sandwiches.

'It's the bones of an Ionian monk,'

said one grey professor. For weeks they took photos of the dear monk. They

measured his skull, his shins, his dear elbows; they took scrapings from his

pelvis, they took a plaster cast of the dear fellow's teeth, they dusted him

with resin and preserving powders and finally the professors had all agreed

,

the Monk was one thousand five hundred years old. 'Which

accounts for him being dead,' said the priest, and that was that.

Money! That was the trouble. Money!

The parish was spiritually solvent but financially bankrupt. Money! The Lord

will provide, but to date he was behind with his payments. Money!

Father Rudden had tried everything to

raise

funds,

he even went to the bank. 'Don't be a

fool, Father!' said the manager, 'Put that gun down.' Money! There was the

occasion he'd promised to make fire to fall from heaven. The church had been

packed. At the psychological moment the priest had mounted the pulpit and

called loudly ' I command fire to fall from heaven!' A painful silence

followed. The priest seemed uneasy. He repeated his invocation much louder, '1

command fire to fall from heaven!' The sibilant voice of the verger came

wafting hysterically from the loft.

'Just a minute, Father, the

cat's

pissed on the matches!'

It had been a black day for the

church. Money! That was the trouble. His own shoes were so worn he knew every

pebble in the church drive by touch. He poked a little gold nut of cheap

tobacco into his pipe. As he drew smoke he looked at the honeyed stone of St

Theresa, the church he had pastored for thirty years. A pair of nesting doves

flew from the ivy on the tower. It was pretty quiet around here.

There had been a little excitement

during the insurgence; the Sinn Fein had held all their meetings in the bell

tower and in consequence

were

all stone deaf. The

priest didn't like bloodshed, after all we only have a limited amount, but what

was he to

do ?

Freedom! The word had been burning

through the land for nearly four hundred years. The Irish had won battles for

everyone but themselves; now the fever of liberty was at the high peak of

delirium, common men were incensed by injustice; now the talk was over and the

guns were speaking. Father Rudden had thrown in his lot with 'the lads' and had

harboured gunmen on the run. They had won but alas, even then, Ulster had come

out against the union. For months since the armistice, dozens of little

semi-important men with theodolites and creased

trousers,

were running in all directions in a frenzy of mensuration, threats and

rock-throwing, all trying to agree the new border.

The sound of a male bicycle frame

drew the priest's attention.

There coming up the drive was the

worst Catholic since Genghis Khan.