Queen of the Conqueror: The Life of Matilda, Wife of William I (42 page)

Read Queen of the Conqueror: The Life of Matilda, Wife of William I Online

Authors: Tracy Joanne Borman

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Medieval

Continuing the similarity to her mother’s life, Adela acted as regent for her husband while he was abroad on campaign. Orderic praised her competence: “This noble lady governed her husband’s county well after his departure on crusade.”

9

Judging from her reaction to his return from Antioch, she evidently relished the role just as much as Matilda had. Thanks to her insistence that he return to the Holy Land, she had the chance to exercise her authority to the full, because her husband met his death on this crusade in 1102. Their eldest son, William, would probably then have been old enough to inherit his father’s title, but he was deemed unfit to rule. His mother therefore had him married off to a lady of her household and gave him lands in the north of the principality, well away from court.

This left Adela free to seize the reins of power herself. She proved more than equal to the task, and her shrewd political judgment and wise government were widely praised. Jumièges observed that she “ruled the country nobly for some years,” while Orderic lauded her as a “wise and spirited woman” who ably led the province until her sons had reached maturity.

10

The archbishop of Dol, meanwhile, claimed that although she was a countess, she was “worthy rather of the name of queen.”

11

Having learned from her mother’s example, Adela became active in every sphere of government, wielding authority over political, ecclesiastical, and military matters as well as the administration of justice.

In 1107, Adela’s second son, Theobald, was invested as count of Blois. Theobald was much more stable than his elder brother. He was also entirely subject to his mother’s authority. Just as Matilda had ruled on behalf of her son Robert, so Adela retained power even after Theobald had been made count. Only when she was confident that he would continue the work that she had begun did she gradually cede authority to him.

Even then she remained at the heart of government, advising her son and keeping him firmly under her control—just as Matilda would have done if she had outlived her husband.

It was no doubt at Adela’s instigation that Theobald intervened on her brother Henry’s behalf when he attempted to take Normandy from Robert Curthose in 1106. As the two youngest siblings, Adela and Henry shared a natural affinity, and the countess certainly favored him over their reckless elder brother. On September 28, 1106, forty years to the day since their father had embarked for the conquest of England, Henry defeated his elder brother in the Battle of Tinchbrai and became duke of Normandy, thus reuniting the Norman empire. It was fitting that, through the influence of Adela, the spirit of Matilda had played a part in such a reunification.

In April 1120, Adela finally relinquished the political life and entered the nunnery of Marcigny-sur-Loire. Like her sister Cecilia, she possessed her mother’s piety and would thrive in the religious arena. Jumièges wrote admiringly that she “served God in a praise-worthy manner till the end of her life.”

12

Adela also shared her elder sister’s longevity, and was in her seventieth year when she died in 1137.

Matilda would have taken great pride in Henry’s restoration of the might of the Norman dynasty, even though he had ousted her favorite son from power. Yet her influence over the English monarchy would far outlive her youngest son. Her bloodline would continue for more than a thousand years. Indeed, all sovereigns of England and the United Kingdom, including the present queen, are directly descended from this remarkable woman.

But Matilda’s legacy extends beyond even this extraordinary feat. The first crowned queen of England to be formally recognized as such, she had established a model of female rule that would last for hundreds of years. Thenceforth, the consorts of kings would expect to do far more than fulfill the conventional role of producing heirs. For instance, because the tradition had been set by the first Matilda, her daughter-in-law, Edith-Matilda, the wife of Henry I, was the natural choice for regent when her husband was away. Moreover, Henry subsequently bequeathed his throne to his daughter, even though his nephew Stephen had a stronger claim in the eyes of most of his subjects; clearly, his

mother’s example had inspired a confidence in female rulers that few of his contemporaries shared. In so doing, he became the first English king to put down in written form the right of a daughter to inherit land.

13

Farther afield, other female consorts, such as the formidable Eleanor of Aquitaine, or Isabella the “She-Wolf” of France, the wife of Edward II, would aspire to the same authority and influence over their husbands and their kingdoms that Matilda had exercised to such brilliant effect.

It is a legacy of which Matilda, whose formidable skills of leadership and political guile have been overshadowed by the achievements of her conqueror husband, would heartily have approved.

A nineteenth-century sketch of Matilda, which hints at her diminutive size.

(illustration credit i1.1)

An engraving of a fresco showing William and Matilda that used to adorn the walls of a chapel at St.-Étienne in Caen. The fresco, now lost, is the only known contemporary likeness of Matilda.

(illustration credit i1.2)

A nineteenth-century version of the engraving that formed the frontispiece to Agnes Strickland’s Queens of England series. Here, Matilda bears a striking resemblance to Queen Victoria, which was no doubt intended to flatter the reigning monarch.

(illustration credit i1.3)

Matilda’s abbey of La Trinité (Abbaye aux Dames), Caen. The abbey was dedicated in 1066, prior to William’s invasion of England. Matilda was later buried there, and her tomb can still be seen today.

(illustration credit i1.4)

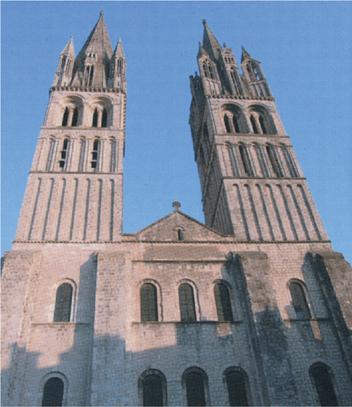

William’s abbey of St.-Étienne (Abbaye aux Hommes), Caen. Both abbeys were commissioned by William and Matilda in 1059 as a penance for defying the papal ban on their marriage.

(illustration credit i1.5)

The castle at Falaise, the town of William’s birth. Legend has it that it was from here that William’s father, Duke Robert, spied Herleva washing clothes in a stream.

(illustration credit i1.6)

The remains of Bonneville-sur-Touques castle, said to be one of William and Matilda’s favorite residences in Normandy.

(illustration credit i1.7)