Raquela (60 page)

Around her the people stood in the noon brilliance. From somewhere behind her in the cemetery she heard the quiet weeping of women kneeling upon the graves of their husbands and sons.

The brief ceremony was over. Raquela lifted a small stone and placed it on the grave. “Rafi, my beloved Rafi,” she whispered.

Each morning during the seven days of the

shiva

, Raquela left the house as soon as there was light in the sky and drove up the hill to Mount Herzl. She put fresh flowers from Papa's garden on Rafi's grave. Then she returned home and composed herself to receive the daily stream of visitors.

It was the ancient wisdom of the

shiva

that brought friends from the whole country to the house, to sit with Raquela and Moshe, with Amnon and Mama, with Jenny and Vivi, to comfort them, to talk to them of Rafi. Hundreds of soldiers came each day. They sat silently in the kitchen, in the dining room, upstairs in Rafi's bedroom, neat and untouched, filled with Rafi's books of poetry, its ceiling a collage of maps he had cut from the

National Geographic

.

Raquela sat among her circle of friends; photos of Rafi's smiling face were on the coffee table; neighbors brought cakes and sweets and poured coffee for the visitors.

Late one morning, a hush fell on the people in the sunken living room. Golda Meir had come to comfort Raquela and Moshe, straight from the Hadassah Hospital in Ein Karem, where she had been undergoing a regular checkup.

She sat on the sofa, beside Raquela; for the first few minutes all the guestsâneighbors, Hadassah nurses, soldiersâwithdrew into themselves in awe. Naomi, Raquela's Kurdish housekeeper, stood frozen, balancing a tray of coffee cups.

Golda was reminiscing; she had known Rafi since he was born. “Our children,” she said simply, “our soldiers. We mothers and fathers”âshe spoke the words on everyone's mindâ“we nurture our children like precious flowers. Then they grow upâ¦and go to war⦔

The whole atmosphere changed. The neighbors began chatting with Golda, as if a member of the family had entered, as if their own mother or grandmother were talking to them, affectionately, informally. Naomi, no longer frozen, moved closer into the circle.

In the evening, a long black limousine pulled up in front of the house. Soon everyone on Bet Hakerem Street knew that the president of Israel, Ephraim Katzir, and his wife, Nina, had come to pay their respects to Raquela and Moshe.

It was President Katzir who had served with Jacob in the Haganah, whose reminiscences brought the first healing laughter to the house. Walking to the French doors opening on to Papa's garden, he turned to his wife. “Over there”âhe pointed beyond the gardenâ“is Bialik Street. Nina, do you remember when you and Jacob were students together at the Yellin Seminar and you lived in a room there on Bialik Street?”

Nina smiled. “How could I forget?”

“And you remember how I used to come evenings to visit you?”

Mama interrupted. “And do

you

remember, Ephraim”âher eyes were sparkling mischievouslyâ“how you used to jump out of Nina's window at night?”

President Katzir's round face broke into a smile. “I didn't want to disturb the landlady.”

The period of mourning came to an end. Raquela arose, dressed carefully, arranged her hair and returned to work.

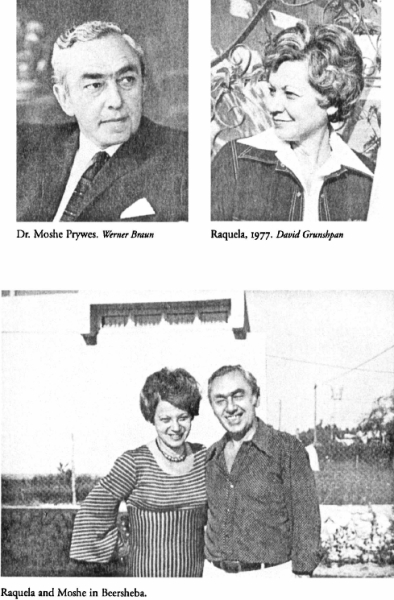

Once again she spent half the week in Jerusalem in the mother-and-child-care clinics, and the other half in Beersheba, in the hospital, visiting the Bedouin Arabs in their tents and houses and the new immigrants in their modest homes.

She plunged into work. Work was the road to recovery. Her projects multipliedâprojects to keep newborn babies alive.

In Beersheba, she created a new studyâto find the causes and a cure for the dangerous hepatitis rampant among newborn babies from Arab lands.

Her days were crowded; friends and family came each evening, surrounding her with warmth and compassion. She was coping. Again she was the gracious hostess, pouring coffee, serving the cakes and pies she had baked. She knew herself; she knew her own feelings, and all day she could control them, though hardly a moment passed that she did not think of Rafi.

It was only at night that the loneliness, the loss, the pain and grief, refused to be controlled.

In bed, with Moshe holding her tightly, she wept.

“How much longer, Moshe? How many more sons must die before peace comes? What can we do, Moshe?”

“We go on living,” he said.

*

Major General Mandler was killed in action on the Canal on the eighth day of the war.

*

A solemn day of mourning for the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

R

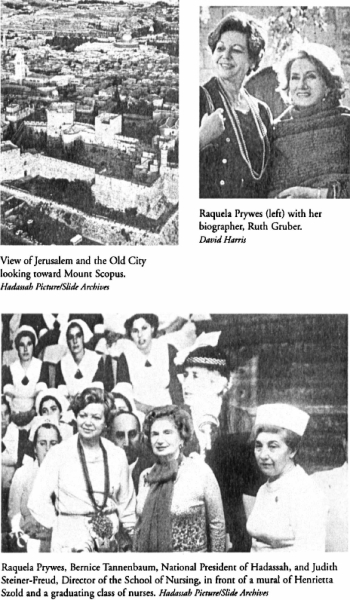

aquela enjoyed the celebrity she won after the book appeared. Letters reached her from admirers around the world. People stopped her on the streets of Jerusalem to congratulate her. She had become a heroine in her own land during her lifetime.

In September 1978, she and her husband, Dr. Moshe Prywes, came to the United States. They were in America barely a week when Doctor Prywes suffered a heart attack. Open heart surgery left him paralyzed, and for seven months Raquela nursed him in the hospital. Exhausted, she then suffered a heart attack. Immediately following surgery she contracted hepatitis from the blood transfusion.

El Al turned one of its aircraft into a hospital plane and flew them on stretchers to Israel. Moshe was taken to Hadassah's Rehabilitation Center on Mount Scopus, where he learned to walk again. Raquela was treated in Hadassah's hospital in Ein Kerem. But the hepatitis destroyed her liver.

She lived until March 1985. During those last months, at 60, she kept herself alive to hold her first granddaughter, little Noa, in her arms.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.