Authors: Nina Planck

Real Food (31 page)

The vast set of data from the prestigious, long-running Framingham study will provide rich research material for years to

come. For now, consider this fact. According to Dr. William Castelli, director of the Framingham study, "the more saturated

fat one ate, the more cholesterol one ate . . . the lower the person's serum cholesterol."

25

When Castelli made this astonishing admission in 1992, it didn't make news.

SUPPOSE YOU WERE A DOCTOR, and the patient sitting before you is a fit woman in her midsixties. According to official guidelines,

she has "high" cholesterol of 261 milligrams and "borderline high" LDL of 153 milligrams, but her HDL and triglycerides are

great. Current advice from the National Cholesterol Education Program is to lower total cholesterol and LDL aggressively.

26

What should you do?

Some doctors would write a prescription for a statin drug, which blocks the liver from making cholesterol. Statins are the

best-selling drug in the United States, worth sixteen billion dollars a year. Pfizer, which makes Lipitor, spends sixty million

dollars a year marketing statins to consumers and employs thousands of sales representatives to promote it to doctors.

27

About fifteen million Americans take statins, but under 2004 guidelines, twice that many— thirty-five million people— are

candidates. Cardiologists call statins "aspirin for the heart" and joke about putting them in the water supply.

In this not-quite-hypothetical case, the patient happens to be my mother, and I was glad her doctor didn't prescribe a statin.

Mom doesn't need to worry about her total cholesterol or her LDL. First, total cholesterol is a poor predictor of heart disease

in women and older people. Second, her ratio of total cholesterol to HDL puts her in the "below average" risk category. Third,

in women and men over sixty-five, high LDL means longer life.

28

Statins are highly effective at reducing LDL, and some studies show they can reduce the risk of dying of a heart attack. But

some researchers have doubts. Benefits of statins for total mortality— or death from all causes, the gold standard in epidemiology—

are small or nonexistent. In 2004, Britain was the first country to approve over-the-counter sales of a statin. The

Lancet

objected, noting that five major trials found that death from all causes was similar with and without statins.

29

"Statins have not been shown to provide an overall mortality benefit," wrote the

Lancet

editors.

Statins may work for a fairly small group. "The people who benefit are middle-aged men who are at high risk or have heart

disease," Dr. Beatrice Golomb said. "The benefits do not extend to the elderly or to women." Golomb, who describes herself

as "pro-statin," is a medical professor at the University of California and the lead investigator in a large federally financed

statin study. (Diabetics may also benefit from statins, but it seems sensible to treat the most common form, type 2 diabetes,

with diet first, because diet causes it.)

As with any treatment, benefits must be weighed against costs. Side effects of statins include muscle weakness, nerve damage,

kidney failure, liver damage, and memory loss. A rare but serious side effect is the potentially fatal muscle-wasting disorder

rhab-domyolysis. In 2001 a statin linked to thirty-one rhabdomyolysis deaths was withdrawn. Statins deplete coenzyme Q

10

an antioxidant found in fish, pork, heart, and liver. Used to prevent and treat heart disease in the United States and Japan,

CoQ

10

prevents LDL from being oxidized.

30

"The first thing I do with new heart patients," says cardiologist Dr. Peter Langsjoen, who has reviewed many studies on CoQ

10

, "is take them off statins."

31

What constitutes healthy cholesterol levels is also a matter of debate. The National Cholesterol Education Program says total

cholesterol under 200 milligrams is "desirable." But this target is not particularly useful. First, "total cholesterol" is

not really cholesterol at all, but a composite number equal to HDL, LDL, and 20 percent of triglycerides. We now know that

total cholesterol does not predict heart disease. Despite the bad press, "high LDL" is a poor predictor, too. Other readings

such as triglycerides, blood sugar, and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) are more useful.

Some doctors think it's unwise to reduce cholesterol at all costs.

Attention has focused on "the supposed danger" of high blood cholesterol for fifty years, says Barry Groves, a British researcher

on obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, while "the dangers of low blood cholesterol levels have largely been ignored."

32

Older people, for example, benefit from high cholesterol. Death rates in the elderly from all causes, including heart disease,

are greater with low cholesterol.

33

Thus the

Lancet

advises doctors to be "cautious" about reducing cholesterol in people over sixty-five.

34

Low cholesterol is linked to respiratory disease, HIV, depression, and death by violence or suicide. Low cholesterol is also

associated with another serious cardiovascular disease: stroke.

35

Cholesterol protects against infection, a well-known risk factor for heart disease. Infection leads to inflammation, which

appears in the arterial walls of heart disease patients with normal cholesterol. A good measure of inflammation is CRP, a

risk factor for heart disease.

36

Women with high CRP and healthy cholesterol have twice as many heart attacks.

37

Inflammation is caused by excess omega-6 fats, smoking, and gum disease, another risk factor for heart disease. Exercise

reduces both inflammation and CRP, which is produced in fat cells.

Clearly, there is much more to learn from the lab than just our LDL and HDL levels. Heart disease has many causes. That means

there are no simple answers in diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. On the positive side, there are potentially many cures.

For example, if my mother wanted to lower her LDL without taking drugs, she could eat more fish. Omega-3 fats reduce LDL,

raise HDL, lower triglycerides, prevent clots, reduce blood pressure, and fight inflammation. Fish is powerful stuff— and

it has no side effects.

Another nutritional approach to reducing LDL (if it worries you) is eating soy, almonds, oats, barley, okra, and eggplant.

Dubbed the

portfolio diet,

this regimen compares favorably with statins in lowering LDL.

38

University of Toronto researchers gave people with high cholesterol three treatments: one group ate a diet "very low" in

saturated fat, the second ate the portfolio diet, and the third took statins. The statin treatment and the portfolio diet

were equally good, each reducing LDL by about 30 percent. The diet low in saturated fat was the least effective, reducing

LDL by only 8 percent. (The low-saturated fat diet, I noted, was also heavy on industrial foods: sunflower oil, fat-free cheese,

egg substitutes, liquid egg whites, and "light" margarine.)

How does the portfolio diet work? Almonds are rich in monounsaturated fat, which lowers LDL. Soy isoflavones lower LDL. The

viscous fiber in whole grains, okra, and eggplant also lowers LDL, perhaps by mopping up bile acid, which forces the liver

to use up cholesterol to make more bile acid. The title of the editorial to accompany this small but promising study in the

Journal of the

American Medical Association

was clear enough: "Diet First, Then Medication."

Kilmer McCully has indeed led a revolution because his work . . . has provided powerful evidence that nutritional deficiencies

are an important cause of heart disease. Not surprisingly, this notion encountered great resistance . . . This is also the

story of a personal struggle by a brilliant physician against a powerful and rigid scientific establishment.

— Dr. Walter Willett, Harvard School of Public Health

IN 1968, KILMER MCCULLY was a young pathologist studying inherited diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. One

day, pediatricians told McCully about an eight-year-old boy who had died of a stroke at the same hospital in 1933. The case

was unusual enough to be written up in the

New England Journal

of Medicine,

and it made McCully curious. When he tracked down the original autopsy slides, he saw the severe arteriosclerosis diagnosed

by the pathologist on the boy's death thirty-five years before.

The boy had a rare genetic disease called homocystinuria, which is caused by faulty B vitamin metabolism and named for homocysteine,

an amino acid that appears in the urine. Other symptoms include long limbs, mild mental retardation, and severe arteriosclerosis.

Children with homocystinuria die of conditions one associates with old age: blood clots, heart attack, stroke. There is no

cure, but high doses of vitamin B

6

help relieve symptoms in about half of patients.

McCully happened to be familiar with homocysteine and cholesterol metabolism.

39

In 1968, the leading theory of arteriosclerosis was that cholesterol attacked the arteries. But McCully didn't believe cholesterol

caused the damage he saw in this case. If cholesterol caused arteriosclerosis, why was there no cholesterol in this boy's

arteries? Mulling it over, McCully recalled animal studies linking deficiency of B vitamins and folk acid to arteriosclerosis,

and he reflected on the cause of homocystinuria: faulty B vitamin metabolism. After many sleepless nights, his eureka moment

came: McCully realized that excess homocysteine due to lack of B vitamins and folic acid caused arteriosclerosis. Cholesterol

did not.

In 1969, McCully described his hypothesis about arteriosclerosis in the

American Journal of Pathology

and proposed a simple treatment: folic acid and B vitamins to keep homocysteine down. At first, this alternative theory of

arteriosclerosis was big news, and scientists all over the world asked for copies of the article. In 1970, the hospital praised

his work as an example of "the unpredictable, important contributions which can come when an imaginative, skilled worker is

given free reign to follow his findings."

But the warm reception was brief. The cholesterol hypothesis was still the establishment view; in 1968, experts had decreed

that 300 milligrams of dietary cholesterol daily was the "safe" upper limit. As news spread of this apparent threat to the

cholesterol theory, the medical world shunned McCully. He lost his research funding and his posts at Harvard and Massachusetts

General Hospital. He went jobless for two years.

Now, more than thirty-five years later, McCully is the chief of pathology at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Boston,

and he treats the affair as a backhanded compliment. "If what I had discovered was unimportant, no one would have cared,"

McCully told me brightly.

40

He can afford to be magnanimous, because today the role of homocysteine is widely accepted. The landmark Physicians' Health

Study on diet and heart disease found that male doctors with high homocysteine were three times more likely to have a heart

attack than those with normal levels. In the large and prestigious Nurses' Health Study, women who ate the least folic acid

and vitamin B

6

had the highest heart-related death rates. The famous Framingham Heart Study also linked homocysteine to heart disease. McCully's

rehabilitation is complete. He is known as the "father of homocysteine."

About twenty human trials examining homocysteine are under way all over the world. McCully is supervising the Homocysteine

Study, a national clinical trial of two thousand veterans sponsored by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, in which people

with kidney failure— a risk factor for heart disease— are taking a placebo or large doses of folic acid and vitamins B

6

and B

12

.

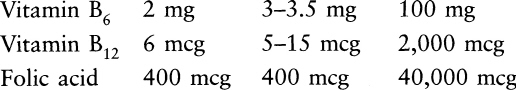

B VITAMINS AND FOLIC ACID IN THE HOMOCYSTEINE STUDY

Note the large vitamin doses in the Homocysteine Study (HOST). Folic acid and B vitamins are perfectly safe.

RDA* Ideal RDA Dady dose in HOST

Dady dose in HOST