Real Food (32 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

* Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA)

According to Kilmer McCully,

According to Kilmer McCully,

The Heart Revolution

The normal role of homocysteine is to control growth and support tissue formation, but in excess, it damages the cells of

arterial walls, destroys the elasticity of the artery, and contributes to calcification of plaques. Vitamins help by reducing

homocysteine. Folic acid and vitamin B

12

convert it to harmless methionine, and vitamin B

6

converts it to cysteine, which is excreted. Less well known nutrients betaine and choline also reduce homocysteine.

The actions of homocysteine fit with what we know about heart disease. It raises triglycerides and forms oxidized LDL, which

causes arteriosclerosis.

41

Homocysteine travels on LDL, which explains the high LDL seen in some people with heart disease. In addition to diet, many

other factors— old age, menopause, smoking, diabetes, lack of exercise, being male, high blood pressure— raise homocysteine,

and every one is linked to heart disease. "All along, it was homocysteine causing the damage," writes McCully, "while cholesterol

was getting the blame."

A popular parlor game in cholesterol circles is solving the mystery known as the French Paradox. Why do the French have low

rates of heart disease despite relatively high blood cholesterol and a diet rich in saturated fats? The French Paradox is

only paradoxical if you believe that natural saturated fats cause heart disease, of course. But let's pretend they do for

the moment. Perhaps red wine is the answer, or smaller portions.

McCully believes the key to the mystery is the pate, sauteed calves' liver, and sweetbreads the French are so fond of. Liver

and organ meats are superlative sources of folic acid and B vitamins, which keep homocysteine levels low. Homocysteine also

explains why people from Papua New Guinea to Nigeria can eat liberal amounts of saturated fat and yet escape heart disease—

another paradox for the conventional wisdom. Traditional diets are low in white flour and sugar (which deplete B vitamins)

and rich in meat, liver, fish, whole grains, and green vegetables, all of which are good sources of folic acid and B vitamins.

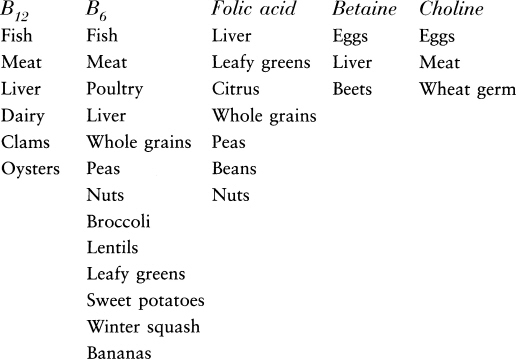

WHAT TO EAT TO KEEP HOMOCYSTEINE LOW

Folic acid, vitamins B. and B10, betaine, and choline reduce homocysteine. Note that B12 is found only in animal foods.

To keep homocysteine levels healthy, eat beef, liver, oysters, eggs, whole grains, and green vegetables. Remember that vitamin

B

12

is found only in animal foods, especially salmon, tuna, cheese, eggs, liver, beef, and lamb. Also, nutrients are lost when

food is processed.

About 80 percent of folic acid disappears when whole wheat flour is milled into white flour, and vitamin B

6

is easily damaged by heat. Thus canned tuna contains half as much B6 as fresh tuna. Vitamin B

12

is more robust to heat, but microwaves damage nutrients much more than conventional heat.

McCully was not the first to blame industrial foods for heart disease, but his discovery about homocysteine was a giant leap

forward in our understanding of how, exactly, refined foods damage the arteries. "The first case of heart disease as it is

known today was reported in 1912, the second in 1919, and since then it has developed into a major killer," wrote Adelle Davis

in

Let's

Get Well.

"The obvious change has been the ever-increasing consumption of refined foods and hydrogenated fats. The populations of the

world living today on unrefined foods, in which nature packages with her fats all the nutrients needed to utilize them, do

not develop heart disease." She was writing in 1965. More than forty years later, Adelle Davis's books are still worth reading.

Even more remarkable, her work is cutting edge.

BEYOND CHOLESTEROL

What Causes Heart Disease

• Deficiency of any of the following: omega-3 fats; folic acid, vitamins B

6

and B

12

; antioxidants, including CoQ

10

and vitamins C and E

• Excess omega-6 fats (polyunsaturated vegetable oils)

• Inflammation (from infection and excess corn oil)

• Oxidized cholesterol (from free radicals in the body and powdered eggs and milk)

• Sugar

• Trans fats (hydrogenated oils)

A Few Risk Factors

• Age (84 percent of people who die of heart disease are sixty-five or older)

• Excess weight, particularly belly fat

• Sedentary lifestyle

• Diabetes (also metabolic syndrome, or prediabetes)

• Family history of heart disease

• High blood pressure

• High C-Reactive Protein (an indication of inflammation)

• Kidney and gum disease

• Menopause

• Smoking

• Thyroid disease

• High blood sugar

IN THE EARLY 19 70S, my father's parents came to visit us in Buffalo, New York, en route to Yugoslavia. Then, as now, we ate

simple food, always made from scratch: some protein, whole grains, vegetables, a green salad. Sugar was a treat. As they left,

my grandfather said cheerfully, "Let's hope there's dessert in Yugoslavia!"

It is said that every household resembles a small nation-state. If so, each family has its Department of Health and its food

and cooking policies. In our house, my mother (like most mothers) wrote the law. Like most daughters, I left home, founded

a new colony of sorts, and wrote my own (vegan and vegetarian) laws. When that turned out badly, I was happy to come home

to the foods I'd grown up eating, but I also wanted to know what science had to say about them. Now I am satisfied that butter

and eggs are good for you.

It is not easy to decide what to eat. There are virtually no limits today. We are not like foragers, who found a beehive dripping

with honey only now and then; we are not like the babies in the Clara Davis experiments, who could choose only from nutritious

foods. And things move fast. In the modern food industry, novelty and technical wizardry are the rule. In the United States,

ten thousand new processed foods come on the market each year, and it seems a new diet is always climbing the bestseller list.

Unlike industrial food, real food is fundamentally conservative. It is the food you already know: roast chicken, tomato salad

with olive oil, creamed spinach, sourdough bread, peach ice cream. To me, that's a relief. When you rule out industrial foods

altogether, it does simplify things a bit.

The quest for the right diet is not a modern conundrum. It is not merely the result of unprecedented variety and abundance

or even of the profusion of contradictory nutritional advice. On the contrary, our search for the right food is as old as

eating itself. Since prehistoric times, every human has asked:

what's for dinner?

Culture undoubtedly plays a role in how we decide what to eat. Hindus don't eat cows, for example. But culture is a minor

determinant compared with nutritional needs, which traditionally trump all other factors. What will nourish the body for a

day's labor, through a long winter, or to recover from an infection? Survival alone is not enough. For men as well as women,

food must also be adequate to ensure fertility. For most creatures, nutrition is simple: instinct rules. Insect or mammal,

herbivore or carnivore, the menu is typically short. Parsnip worms eat parsnip seeds, ladybugs eat aphids, koala bears eat

eucalyptus leaves, zebras eat grass, and lions eat zebras. But we are omnivores. We can and will eat anything.

Omnivores are highly adaptable and humans especially so. That's why we occupy not one ecological niche but many, from frozen

tundra to moist forest to scorched desert. This is a singular achievement; no other species lives in all the major habitats.

A penchant for trying new foods in new situations was key to the success of all the

Homo

tribes, including ours. "When the eucalyptus trees all die in a given place, so do all the koalas," writes Richard Manning,

"but omnivores have options."

Along with these options comes a unique problem, namely, that not everything that looks like food is edible and some things

might be poisonous. In 1976, the psychologist Paul Rozin called this the

omnivore's dilemma.

One eucalyptus tree meets all the nutritional needs of a hungry koala, but an omnivore must successfully balance curiosity

and caution to survive. Various tactics come in handy. As social animals, we pass the word along that this berry or that insect

is to be eaten or avoided. Contemporary hunter-gatherers without formal education in botany or zoology can identify hundreds

of plant and animal species and many details about their medicinal or toxic properties, life cycles, habitat, and habits.

The Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker calls this

intuitive biology,

and it is surely the product of the omnivore's quandary. Omnivores also avoid things that smell rotten, and only nibble at

unfamiliar foods. Researchers describe another tactic as the "poisoned partner effect." If a rat smelling of a particular

food is looking poorly, other rats will avoid that food.

Even so, omnivores do get things wrong, especially in new situations, and suffer for it. When Americans settled west of the

Appalachians in the 1800s, people began to get "milk sickness," which caused weakness, nausea, thirst, foul breath, and finally,

death. In certain Indiana and Ohio counties, the illness was rampant. It was noticeable that where people were dying, cattle

with similar symptoms got the "trembles." The twin epidemics aroused the curiosity of an Illinois midwife, Anna Pierce, who

asked a local Shawnee woman for advice. The woman led her directly to white snakeroot, a plant that caused the trembles in

cows and poisoned the milk. The active compound of snakeroot— tremetol— was not identified until 1928. One doctor who doubted

that Pierce had found the cause of milk sickness ate snakeroot to prove her wrong; he promptly died.

In modern life, the risk of unintentional poisoning is greatly reduced. We don't have to guess which foods might make us sick

because the food supply is no longer wild. Botany is now a formal body of knowledge, scientifically tested. My parents taught

me that rhubarb leaves contain toxic oxalic acid, while the stems make great pie; they learned that from books, not at the

knee of the local wise woman. But the modern omnivore is not out of the woods yet. The risk of nutritional imbalance is great.

Rozin writes: "A koala that eats only eucalyptus leaves has no such risk; it is adapted to survive on the nutrients eucalyptus

has to offer. Similarly, a lion rarely risks imbalance, because the zebras it eats already contain the range of nutrients

it needs. But the generalist happens upon many potential foods that have nutritive value, but are not complete nutrients.

Appropriate combinations of foods must be selected."

There's the rub. Unlike lions and other specialists, we have to think about which foods are nourishing, and in this respect,

life is more confusing than ever. Modern humans face a vast choice of food, far beyond what was ever available before in both

variety and quantity. Although traditional diets vary widely, in any given place, humans always ate a limited menu of local,

seasonal foods.

Together, technology and migration have produced an unprecedented profusion of food. Freezing, canning, pasteurization, and

other technologies extend the shelf life of perishable foods. Global trade has expanded variety beyond the imagination of

any hunter-gatherer. The coffee, tea, spice, and olive oil trades are thousands of years old, but even this ancient commerce

is recent in evolutionary time. The scale of modern trade is astounding. When there is snow on the ground, we can eat sweet

corn and tomatoes; in cold climates, mangos and pineapples are easy to come by; in most American towns, Italian olive oil,

Chilean grapes, and Thai shrimp are not luxuries but staples. Perhaps the most profound contribution of technology is the

creation of truly new foods such as canola oil and margarine.

As exotic foods have circled the globe, so have people. Migration has loosened, if not severed, the bonds between people and

their traditional foods. For most of human history, a child ate what her parents ate: yogurt in Turkey, miso soup in Japan,

cheese in the Swiss Alps. Today, the foods of every culture, from hummus to tortillas, mingle in restaurants, shops, and markets.

The United States, a land of immigrants, is particularly diverse— and apt to slough off tradition— but something similar occurs

in most wealthy nations: the typical diet is not the traditional one. The modern omnivore's dilemma is acute.

THE OMNIVORE'S

FEAST—

WHAT'S FOR DINNER?

• Eat generous amounts of fresh fruits and vegetables daily

• Eat wild fish and seafood often

• Eat meat, game, poultry, and eggs from wild, pastured, and grass-fed animals often

• Eat full-fat dairy foods, ideally raw and unhomogenized from grass-fed cows, often

• Eat only traditional fats, including butter, lard, poultry fat, coconut oil, and olive oil

• Eat whole grains and legumes

• Eat cultured and fermented foods such as yogurt, sauerkraut, miso, and sourdough bread

• Eat unrefined sweeteners such as raw honey, evaporated cane juice, and pure maple syrup in moderation

For three million years, we were skilled fishermen and hunters, able to kill giant animals such as wooly mammoths and fast

ones such as wild horses, not to mention lions, sloths, bears, moose, giant lemurs, and camels. We hunted with a powerful

combination of tools unique in the animal world: sharp spears, binocular vision, hand-eye coordination, and teamwork. We filled

up on fish and game when we could, and in between we made do with every berry, tuber, and insect we could find. This dietary

strategy— mostly predator, part forager— was simple and effective.

Then, in the blink of an evolutionary eye, something catastrophic happened. About thirty-five thousand years ago, the megafauna

(big game) dwindled and then disappeared. "They became extinct in every habitat without exception," writes the historian Jared

Diamond, "from deserts to cold rain forest and tropical rain forest." We humans were the main predator of these wild animals,

which had thrived for tens of millions of years before we arrived. Until recently the suggestion that we killed them off—

the "overkill hypothesis"— was ridiculed. Now most scientists agree that the big game were not doomed by an ice age or drought,

but by spears and clubs.

Having depleted our chief source of nutrition, we did what only omnivores can do. We went looking for other foods to eat.

We hunted less big game and began, gradually, to domesticate smaller wild animals for meat and milk. We foraged more and began

to nurture wild crops like yams. The result was amazing variety in our diet. When an Iron Age man slipped into a peat bog

in Denmark twenty-two hundred years ago, his stomach held the remains of sixty species of plants. Our brains are wired and

our bodies are built to hunt and gather. Hunger is our motivation, variety is the result, and health is our reward.

Perhaps this explains my urge to forage. At the farm, I enjoy nothing more than picking vegetables for dinner, finding nettles

behind the barn, or cutting watercress from the footbridge over the creek. Browsing the farmers' market always makes me happy.

Even rummaging in the fridge in search of inspiration for dinner is a little adventure.

Variety is the hallmark of the human diet and its greatest pleasure. At my house, there may be a dozen different foods— from

beef to bacon, olive oil to butter, kohlrabi to zucchini— at just one meal. I am not ambitious enough to put sixty vegetables,

much less sixty species, on the dinner table, but when I am shopping for food or cooking dinner, I try to remember the rich

array of life in the last supper of the Iron Age man, and I feel lucky to be an omnivore, blessed with a thousand ways to

eat well and be well.