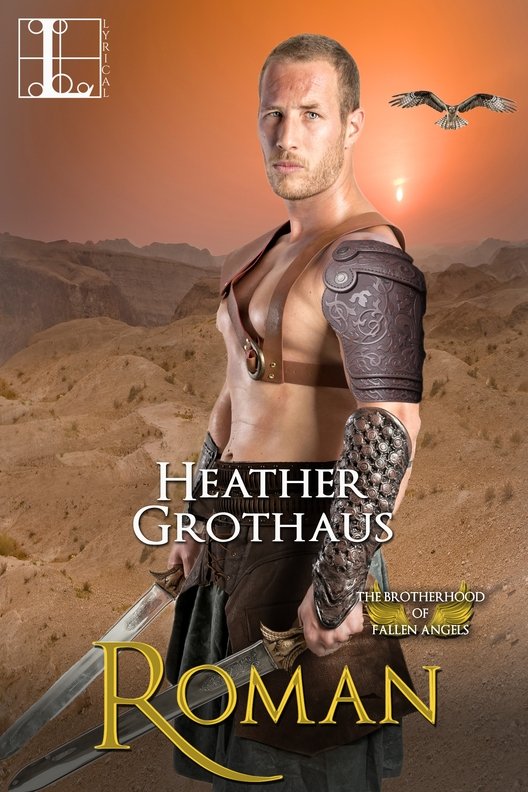

Roman

Authors: Heather Grothaus

ROMAN'S KISS

Isra looked ahead, down the valley, and saw a thick cluster of horses reemerging onto the road leading from Kerak's sandstone motte, a red and white banner flickering like a tiny scrap in the sunset.

She looked up at Roman, but his face was turned to the sky now, as if he was contemplating something only he could see.

Then he turned his head toward her, held out his hand.

Isra placed her fingers into his palm and let him pull her to her feet. Once she was standing he drew her against his chest slowly, deliberately, wrapping his uninjured arm around her shoulders, and Isra held her breath as she looked up and he lowered his head.

“I can wait no more,” he whispered against her mouth, and then he kissed her . . .

Books by Heather Grothaus

THE WARRIOR

Â

THE CHAMPION

Â

THE HIGHLANDER

Â

TAMING THE BEAST

Â

NEVER KISS A STRANGER

Â

NEVER SEDUCE A SCOUNDREL

Â

NEVER LOVE A LORD

Â

VALENTINE

Â

ADRIAN

Â

ROMAN

Â

HIGHLAND BEAST

(with Hannah Howell and Victoria Dahl)

Â

Â

Â

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

ROMAN

The Brotherhood of Fallen Angels

Heather Grothaus

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

ROMAN'S KISS

Books by Heather Grothaus

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Epilogue

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Teaser chapter

Teaser chapter

Copyright Page

Books by Heather Grothaus

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Epilogue

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Teaser chapter

Teaser chapter

Copyright Page

Always.

Prologue

August 1179

Syria

T

he wall came down no more than fifty feet behind Roman, the already hot air contracting around him like a shroud, then exploding with a roar of flames. The blast lifted him from his feet and sent him flying over the bodies of the slain workers who had, only a moment ago, been being prepared for burial. He slammed into the hard-packed dirt and then skidded and tumbled for several yards, his rough brown tunic seeming to melt into his skin.

he wall came down no more than fifty feet behind Roman, the already hot air contracting around him like a shroud, then exploding with a roar of flames. The blast lifted him from his feet and sent him flying over the bodies of the slain workers who had, only a moment ago, been being prepared for burial. He slammed into the hard-packed dirt and then skidded and tumbled for several yards, his rough brown tunic seeming to melt into his skin.

He realized the instant he came to a stop that it wasn't a friction wound he felt; the back of his tunic was afire.

He slapped at the flames and flung himself onto his back as a pair of screaming pillars of fire ran past him, but Roman could barely hear them above the loud squeal the explosion had stuffed into his pounding, spinning head. They weren't flaming pillars; they were men. Men on fire.

Roman pushed himself up on his elbows and looked at the southeast corner of Chastellet's bailey. Where carefully crafted rectangular stonesâmany of which Roman Berg himself had setâonce comprised the fortress's key defense, the wall sagged, framing an inverted wedge of white-hot Syrian sky beyond. Roman's eyes burned and his nose ran as the air was filled with the stink of naphtha and burning sand, burning flesh.

His head jerked as a hand gripped his right biceps. He hadn't heard his apprentice approach, hadn't been able to hear the slim man's shouts over the twisting whine still swelling in his ears. But Osbert's mouth was moving wildly, his teeth flashing behind cracked lips as he pulled futilely at Roman with one hand while gesturing with the pick in his other to the barracks left standing against the eastern wall. Roman glanced in that direction, but the shelter held little interest for him as his eyes gaze fell upon a hunting falcon tethered to a post just outside one of the doorways. The bird of prey's hood swiveled and twitched, as if listening to the commotion Roman could not hear. Roman found himself fascinated by the creature's movements . . .

A hand struck Roman's cheek, and he reluctantly turned his attention back to Osbert.

Come on! his apprentice mouthed, spittle flying, his eyes bulging.

Roman frowned, hesitated. He was confused. What was happening? Why had the wall fallen? Why were there little shadows crawling like insects across Osbert's face, across the dirt of the bailey . . . ?

The arrow shaft appeared in Osbert's neck so suddenly, it was as if by magic. Blood spurted out of the hole in the side opposite the fletching. Although Osbert's mouth opened once again in preparation for what Roman surmised was to have been a scream of agony, he doubted any sound emerged. The apprentice pitched forward onto Roman, the man's pick arcing smoothly down into the dirt, and he felt Osbert's hot blood soak through his tunic and run down his chest as arrows suddenly fell like rain on the bailey.

Roman pushed the apprentice's body from him as he skittered backward. A zinging pain shot up his left arm from his smallest finger and he jerked his hand from the yard, looking at the arrow that had shot a wedge of flesh from his hand before burying itself deep in the dirt. Another landed precisely between his bent knees. Roman's head swam, throbbed; his tongue seemed to swell in his mouth.

Stay still? Move? What sort of nightmare was this?

Roman looked up and saw Chastellet's remaining workers, Templars, servantsâall that were left on this sixth day of siegeâcrisscrossing the bailey frantically, many of them pausing in midstride to demonstrate the bow-backed pose of defeat before crumpling to the ground, their bodies stubbled with arrows. Roman staggered to his feet at last, shook his head violently despite the pain it caused.

His hearing came back with a slow whoosh, letting in the roar of screams, the pounding of feet, the clanging of metal. Reality crashed upon him as surely as the wall that had crushed the men standing just behind him: Chastellet had been breached. The wall had been the first wave of attack.

The arrows falling around him with whistles and pings: the second wave. Which meant . . .

Roman again raised his eyes to the collapsed section of wall just as the undulating crowd of Saracens crested the rise and charged toward the opening. Some were on horseback, some afoot. All with weapons raised and yelling their terrible, unintelligible screams.

The third wave.

Roman reached down and retrieved Osbert's pick from the dirt, all the while keeping his eyes on the force advancing toward him. The warrior monks were already engaging the invaders, their long, double-edged swords swinging without hesitation. But even Roman Bergânever a warrior until six days beforeâknew the sheer numbers of Saracens pouring into Chastellet's walls meant defeat was expected.

He thought briefly of Lord Adrian Hailsworth, Chastellet's architect and Roman's principal at the site, and wondered if the brilliant man would live to see the total destruction of the fortress both men had labored over in their own ways.

He thought of Lord Constantine Gerard, a layman general of noble rank who was to have left Chastellet a week earlier. An earl, Roman thought. Was he already dead?

They were both good men, noble men, casually treating Roman as their equal. Even Hailsworthâarrogant as he wasâhad taken to the practice of deferring to Roman's skill and experience when appropriate. Now whatever differences between Roman and the titled men's backgrounds and pedigrees were truly washed away, as Roman would battle as they battled, fight as they would fight, to defend the place Roman considered to be the pinnacle of his life's work.

The fortress that would likely become his tomb.

He began to stride toward the line of Templars who were miraculously holding back the onslaught against them. Without pause, he reached down and pulled a broadsword from the limp grasp of a fallen soldier. But he kept the pick in his right hand; it was familiar there, and he knew just how to utilize it.

As if his earlier thoughts had conjured the man, Roman saw Constantine Gerard leaping and sidling through the fight toward him. His helm was missing, but he held forth his long shield as he dispatched a rogue attacker. Somehow, Roman must have caught Gerard's eye, for the general paused and banged his sword against his shield before raising it in Roman's direction.

“God be with you, brother,” he shouted at Roman.

Roman lifted his weapons and crossed them with a clang over his head. “For Chastellet!” Roman returned against the cracking of his voice.

And then General Constantine Gerard was gone, the last of him Roman saw was his tawny mane flowing behind him as he threw himself into the thick of the battle. Roman turned once more toward the breach, walking deliberately, his weapons flanking him like the squires he had no right to claim.

Yes, he knew he could fall this day. But for as long as he was able to swing his tools, he would swing.

He stopped then and braced his feet as a Saracen soldier broke away from his comrades and galloped toward him on horseback. The man's robes rose and fell in rhythm to his mount's charge, and he held a long scimitar in his right hand, a small hatchet in his left, guiding his finely built horse with nothing more than his knees.

Roman crouched lower, holding forth the broadsword and drawing the pick behind his head. He opened his mouth to let out a cry of attack . . .

He came awake with a gasp, inadvertently sucking in some of the silty dirt from the floor of the cave. Roman fell into a coughing fit as he sat up fully, noticing that he clutched at his shoulder out of habit. He released his arm and reached for the now nearly empty skin of wine the Spaniard had left behind for him.

“To pass the time, yes?” Valentine Alesander had said with a wry grin as he'd tossed it down from atop his horse. Then he'd disappeared down the trail in the spreading dusk.

A short, creaking chirp echoed in the cave, interrupting the memory.

Roman gained his feet and walked to the opening of the cave where the hunting falcon was tethered. He stroked Lou's back with one finger as he looked down on the walled city of Damascus, which would soon lay in shadow for the third time with Roman as witness. Three days. Valentine Alesander had left Roman in the cave three days ago.

“They will be praying soon,” Valentine had said. “It is my best opportunity.”

Roman scrubbed a hand over his bristly face as if he would wipe the thick air and his troubled thoughts away. Then he sighed and placed his hands on his hips. It was of no use; the cave seemed to be full of ghosts now: days past living on in his dreams, voices in his head.

Something had gone wrong. Either the Spaniard had been caught or he had not even attempted to gain entry into Saladin's prison to free Adrian Hailsworth and Constantine Gerard. Perhaps he had instead maneuvered his horse around the wall and gone on past the city, taking the sack of Chastellet coin with him. He'd already proven he could disappear into the native population; Roman had nearly killed Alesander himself upon their first meeting at the ruined fortress, thinking him Saracen.

Roman stalked to the back of the cave, squatted down, and checked his bag again; it was still cinched tightly, the other sack of gold secure inside. Then Roman rose and paced the width of the crude shelter.

Whether Alesander had absconded with the coin or been captured himself, there was clearly no one to rescue Roman's friends. And if the Spaniard

was

caught, his blood was on Roman's hands. Roman's shoulder ached where the man had reseated the joint for him, dislocated for weeks, and he kneaded the biceps which seemed so much smaller than it had been only weeks ago.

was

caught, his blood was on Roman's hands. Roman's shoulder ached where the man had reseated the joint for him, dislocated for weeks, and he kneaded the biceps which seemed so much smaller than it had been only weeks ago.

Valentine Alesander had rescued him from the midden heap of Chastelletâits cisterns stuffed with corpses and its walls adorned with carrion birds; rescued him from the cesspool of his own mind, which echoed with the screams of the dying; the sounds of arrows finding deep flesh; the shame of being the one left behind, the one left alive. The Spaniard had made Roman's body whole again, despite the healing gashes and still-dark contusions beneath his tunic and chausses. And he had led Roman to Damascus, where the only two men on earth Roman could claim as friends were being held by the conquerors of Chastellet.

If they weren't already dead.

Roman, like Chastellet, had fallen. Had he not been struck so many times to the temple, perhaps he would have realized the true folly of dragging himself into the exposed bailey once more to save the life of the hunting bird left abandoned and tethered to its perchâthe same one that now stood guard at the cave's entrance. But in Roman's swollen, fevered reasoning, there had been naught else for it. His weakness and injuries had rendered him incapable of saving Chastellet, but there had been a creature before himâone totally innocent of man's folly and politicsâthat he

could

save. He had decided to let the attempt be on his soul, then, and damn him if it would.

could

save. He had decided to let the attempt be on his soul, then, and damn him if it would.

Lou chirped againâa questioning soundâand Roman went once more to the falcon, who had come to mean so much to him since that bloody day.

“Naught else for it again, is there, Lou?” he said quietly, stroking the bird's feathers. The falcon tolerated Roman's touch, but Roman knew he was impatient. Lou needed to fly. And so did Roman.

He looked back to the opening of the cave. If he did nothing to save the three men hidden somewhere in the city below, he might as well return to the ruin that was Chastellet and drop from a rope hung from its highest crumbled wall. It would be better than rotting here in this cave, waiting for a Spaniard who was clearly never coming back.

Roman returned to his satchel again, picking it up and looping the strap over his back before donning the leather hood that fit tightly over his skull and draped onto his shoulders like a short cape. He had no robe, no cloak, nothing else to disguise his large body and English coloring. The hood would have to do. The guards would likely kill him as soon as he passed through the gates any matter, if he made it that far.

He had no gauntlet for Lou, but the falcon had been content to ride upon Roman's shoulder from Chastellet. He picked loose the leather tie keeping the bird prisoner, and then leaned down, easing the falcon onto the edge of the hood.

“Going on an adventure, Lou.”

The bird didn't respond, but sidled a bit higher on Roman's shoulder, closer to his ear. Roman found the weight of the creature, the grip of its talons, comforting, as if he truly had a comrade in the falcon.

“I'll not keep hold of your tether, though,” he said, turning and walking out of the cave without hesitation and setting his boots upon the narrow, twisting animal path that led down the hillside. “I'm likely walking to my own death, and I'd not have yours on my conscience as well. I'll remove your hood before I enter the city. You'll be free.”

Roman considered as he tromped down the mountain in the lengthening shadows that, if he were being truly magnanimous, he would remove the bird's blind now. But he could not yet bear itâthe thought of being totally alone at what could again be the last hour of his life. That void had been with him since he was a boy, had it notâthe solitude? He thought with some shame that he should be used to it by now.

He walked quickly among the dunes dotted with scrubby brush at the base of the mountain, seeking the shortest path to gain the packed road leading into the city. Roman guessed that a lone man afoot with nothing more than a single bag was unlikely to draw immediate scrutiny from the guards atop the wall. The sun was swiftly sliding down the sky behind him, throwing a long, deep shadow on the road before him, and Roman hunched into it, made it his companion along with the falcon on his shoulder.

Other books

The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara

Born Into Destiny: A Forsaken Sinners MC Series Novella by Shelly Morgan

The Dragon's Wrath: Ashes of the Fallen by Brent Roth

Wasted Beauty by Eric Bogosian

Stellar Fox (Castle Federation Book 2) by Glynn Stewart

Mr. Hooligan by Ian Vasquez

Freight Trained by Sarah Curtis

Dai-San - 03 by Eric Van Lustbader

Behold the Stars by Fanetti, Susan

Diamonds in the Dust by Beryl Matthews