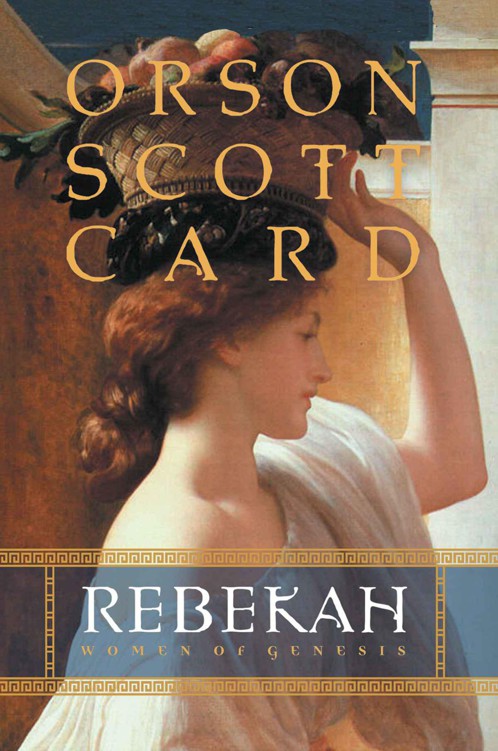

Rebekah: Women of Genesis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, Shadow Mountain

®

. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the position of Shadow Mountain.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Card, Orson Scott.

Rebekah / Orson Scott Card.

p. cm. — (Women of Genesis)

ISBN-10 1-57008-995-7 (hardbound : alk. paper)

ISBN-13 978-1-57008-995-4 (hardbound : alk. paper)

1. Rebekah (Biblical matriarch)—Fiction. 2. Bible. O.T. Genesis—History

of Biblical events—Fiction. 3. Women in the Bible—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3553.A655 R427 2001

813’.54—dc21 2001005523

Printed in the United States of America

Publishers Printing, Salt Lake City, Utah

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

To Zina

alight with all the graces you are the joy of this old man’s life

Preface

I used all the sources that previously helped me in writing

Sarah,

the companion volume to this book, and in addition, Norman L. Heap’s

Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob: Servants and Prophets of God

(Family History Publications, Greensboro NC, 1986, 1999). While Dr. Heap places more reliance on non-biblical sources than I do, he performed the valuable service of bringing together all the scattered verses about each figure in the stories of the patriarchs. In particular, his book called my attention to Deborah, the nurse of Rebekah, who had figured in none of my preliminary outlines because I had carelessly overlooked her. And figuring out why Rebekah, alone of all these women, was so close to her nurse throughout her life led me to the whole elaborate invention of the first half of this book.

The task in this novel was to show how good people can sometimes do bad things to those they love most. The story of Rebekah could easily be taken as a case study in how not to run a family. But if there’s anything I’ve learned in my fifty years of life, it’s that people doing the best they can often get it wrong, and all you can do afterward is try to ameliorate the damage and avoid the same mistakes in the future. Good people aren’t good because they never cause harm to others. They’re good because they treat others the best way they know how, with the understanding that they have. Too often in our public life we condemn people for well-meant errors, and then insist that everyone should forgive people whose errors were intentional and who attempted, not to make amends, but to avoid consequences. Good and bad have been stood on their head by people who should have known better. How do we live in such a world? Isaac was headed for a disastrously wrong decision; Rebekah chose an equally wrong method of stopping him. The question of which wrong was worse is not even interesting to me. They both meant well; they both acted badly; but in the end, the result was a good one because good people made the best of it despite all the mistakes.

Much of what goes on in this novel is speculation. I know that some people have a specific set of theological “meanings” assigned to Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac, and there is no room in their picture of these men for Isaac to have had anything other than perfect agreement with all that his father did. While that is not impossible, I find it highly unlikely. Prophets are human beings, too, and the feelings of human beings are not always responsive to our intellectual understanding. Isaac might well have agreed that his father made the right choice. But to me it seems inevitable that Isaac would come away from that scene on a mountain in Moriah with a great deal of pain at the knowledge that when his father was commanded to kill him, the old man did

not

love his son so much that he could not do it.

Believers in biblical inerrancy will be annoyed by some of my choices. For instance, I don’t take literally all three accounts in Genesis of a husband passing off his wife as his sister in order to avoid getting killed by a king. It happens once with Sarah, Abraham, and Pharaoh; once with Sarah, Abraham, and Abimelech of Gerar; and a third time with Rebekah, Isaac, and Abimelech of Gerar. My conclusion that the two Abimelech versions of the story are really variant accounts of the same story is reinforced by the fact that both end with a newly-dug well being named “Beersheba.” I chose to leave the digging and naming of Beersheba with Isaac, and the incident of deceiving a dangerous king with Abraham, Sarah, and Pharaoh. I’d rather think that the Bible has included three variants of the same story than to think that these people were so dumb that they would dig the same well and give it the same name twice. Not to mention what a slow learner Abimelech apparently was—even if, as some have speculated, the Abimelech who flirted with Rebekah was the son of the Abimelech who had the hots for Sarah.

In preparing this novel I am indebted, as always, to a small corps of friends and family who read the chapters as they spew forth from the LaserJet. Kristine, my wife, is always there to read and keep me from the most egregious errors. She was joined on this novel by my daughter Emily, who reads like the perceptive actor that she is, with a keen eye for what characters would and would not do, and by our friends Erin and Phillip Absher, who were with us for much of the summer when I wrote the book. Erin, in particular, alerted me to an imbalance in my portrayal of one of the characters; unfortunately, she did so when I was right up against a deadline and had no time to make the substantial corrections that would be required. But once aware of the problem, I could never have allowed the book to be published as it was. So the deadline was pushed back one more day as I made the changes. It’s a better book for her having had the courage to tell me such unwelcome news. Another whose prereading and comments were much appreciated is Kathryn H. Kidd, who was far too generous with her time during a month when she had precious little of it to spare. And Kay McVey’s encouragement and enthusiasm for the book reassured me that maybe, despite all the difficulties, this story was going to work.

Passages of this book were written in such farflung places as Laie, Hawaii; the home of my beloved cousins Mark and Margaret Park in Los Angeles; in a rented beach house in Corolla, North Carolina; and on a grassy shore near Cape Canaveral, where I wrote a chapter and a half while waiting for our friend Dan Berry to take off on a mission in the space shuttle.

Cory Maxwell is the perspicacious publisher who first caught the vision of these books and made it possible for the project to go forward. Sheri Dew inherited the project when Deseret Book bought out Bookcraft; she became my mother confessor during some bleak days, and gave me a bucket to bail with more than once. My editors, Emily Watts and Richard Peterson, showed unbelievable patience when this book was shamefully late, and if it comes out on time, it’s only because of the extraordinary lengths they and others at Deseret Book went to to compensate for my tardiness. Kathie Terry, Andrew Willis, and Tom Haraldsen did an excellent job of promoting this series outside the normal territory of the publishing company. And Tom Doherty astonished me by picking up the paperback rights to books that are definitely

not

science fiction or fantasy. You’re too good to me, Tom! But don’t stop.

During a very hard year in our lives, my family has stood by me—or, rather, we’ve all stood by each other. My wife, Kristine, and my children, Geoffrey, Emily, and Zina, have borne me up through all sorrows and given purpose to my work. Zina, especially, has dealt with more death than a child her age should see, and yet remains the light of my old age. And the two children who are not with us now were nevertheless very much in my heart as I wrote. I have written elsewhere of my love and gratitude for those who were good to Charlie Ben during his life and who reached out to us since his passing, as well as those who helped comfort us after the brief life of our youngest child, Erin Louisa. Given the story I have told in this book, it seems appropriate for me to use these pages to thank God for letting me have the joy of all these children in my life. No one brings you more woe, more worry, or more rejoicing than your children. Blessed is he who has a quiver full.

Part I

Deaf Man's Daughter

Chapter 1

Rebekah’s mother died a few days after she was born, but she never thought of this as something that happened in her childhood. Since she had never known her mother, she had never felt the loss, or at least had not felt it as a change in her life. It was simply the way things were. Other children had mothers to take care of them and scold them and dress them and whack them and tell them stories; Rebekah had her nurse, her cousin Deborah, fifteen years older than her.

Deborah never yelled at Rebekah or spanked her, but that was because of Deborah’s native cheerfulness, not because Rebekah never needed scolding. By the time Rebekah was five, she came to understand that Deborah was simple. She did not understand many of the things that happened around her, could not grasp many of Rebekah’s questions and explanations. Rebekah did not love her any the less; indeed, she appreciated all the more how hard Deborah worked to learn all the tasks she did for her. For answers and understanding, she would talk to her father, or to her older brother Laban. For comfort and kindness she could always count on Deborah.

Rebekah no longer played pranks or hid or teased Deborah, because she could not bear seeing her nurse’s confusion when a prank was discovered. Rebekah soon made her brother Laban stop teasing Deborah. “It’s not fair to fool her,” said Rebekah, which made little impression on Laban. What convinced him was when Rebekah said, “It’s what a coward does, to mock someone who can’t fight back.” As usual, when she finally found the right words to say, Rebekah was able to prevail over her older brother.

The real change in her life, the one that transformed Rebekah’s childhood, was when her father, Bethuel, went deaf. He had not been a young man when she was born, but he was strong enough to carry her everywhere on his shoulders when she was little, letting her listen in on conversations with the men and women of his household, shepherds and farmers and craftsmen, cooks and spinners and weavers. Riding on his shoulders as she did, his voice became far more than words to her. It was a vibration through her whole body; she felt sometimes as though she could hear his voice in her knees and elbows, and when he shouted she felt as if it were her own voice, coming from her own chest, deep, manly tones pouring out of her own throat. Sometimes she resented the fact that in order to say her own words, she had only her small high voice, which sounded silly and inconsequential even to her.