Red Capitalism (3 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

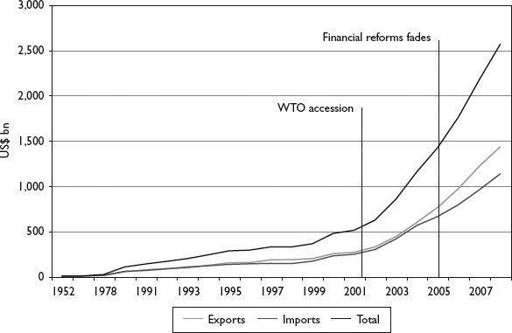

China at last acceded to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in late 2001 after 15 years of difficult negotiations. Zhu saw membership of the WTO as the guarantee of an unalterable international orientation for a China that in the past had too frequently been given to cycles of isolationism. He believed that the WTO would provide the transformational engine for economic and, to a certain extent, political modernization regardless of who controlled the government. His enthusiasm for engagement with the world paid off as trade with China turned white hot in the years that followed (see

Figure 1.2

).

FIGURE 1.2

Trends in imports, exports and total trade, 1999–2007

Source: China Statistical Yearbook 2008

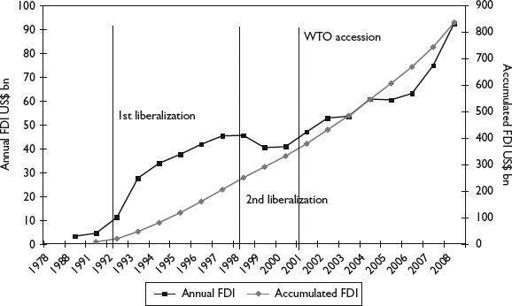

It was not just trade; foreign direct investment also poured in, jumping to unheard-of levels of US$60 billion a year and peaking at over US$92 billion in 2008 as the world’s corporations committed their manufacturing operations to the Chinese market (see

Figure 1.3

). Chairmen in boardrooms everywhere believed with Zhu Rongji that China was on a path of economic liberalization that was irreversible.

FIGURE 1.3

Committed foreign direct investment, 1979–2008

Source: China Statistical Yearbook 2009

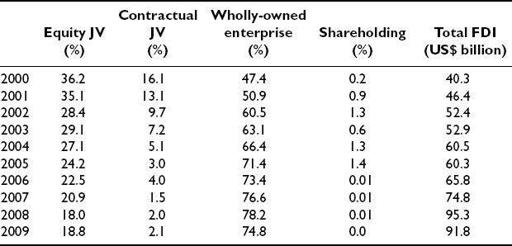

The commitment of these foreign businessmen was not simply a function of belief. In the early years of the twenty-first century, China’s market opened up as it never had before. At the start of economic liberalization in the 1980s, foreign investors had been forced to contend with the practical consequences of the famous “Bird Cage” theory. Trapped in designated economic zones along the eastern seaboard, just as they had been in the Treaty Ports of the Qing Dynasty a hundred years earlier, foreign companies were forced into inefficient joint ventures with unwanted Chinese partners. Then every local government wanted its own zone and its own foreign birds, so that during the 1990s, economic zones proliferated across the country and were eventually no longer “special.” Despite this, even as late as 2000, the joint-venture format accounted for over 50 percent of all foreign-invested corporate structures. After China’s accession to the WTO, this changed rapidly. It seemed that China was open for business after all: by 2008, nearly 80 percent of all foreign investment assumed a wholly-owned enterprise structure (see

Table 1.1

). At long last, the Treaty Port system seemed a thing of the past, as foreign companies had the choice of where and how to invest.

TABLE 1.1

FDI by investment-vehicle structure, 2000–2008

Source: US-China Business Council; as a percent of total utilized FDI

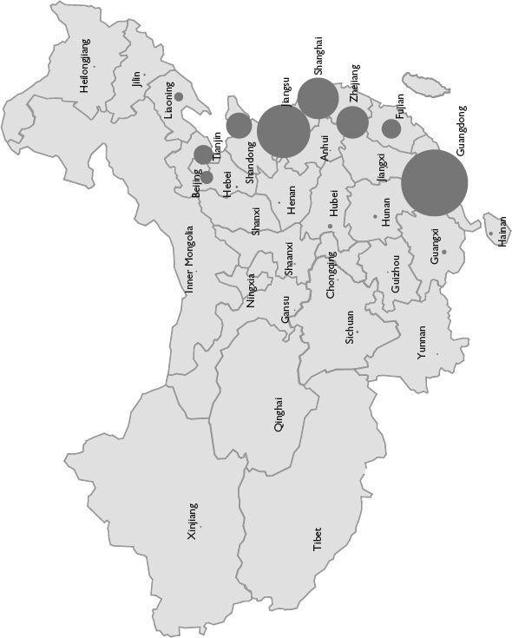

Over the past few years, they have undeniably committed their technologies and management techniques and learned how to work with China’s talented workers to build a world-beating job-creation and export machine. But they have done this in only two areas of China: Guangdong and the Yangzi River Delta comprising Shanghai and southern Jiangsu Province (see

Figure 1.4

). The economies of these two regions are dominated by foreign-invested and private (

waizi and

and

minying ) companies; there is virtually no state sector remaining. These areas consistently attract 70 percent of total foreign direct investment and contribute over 70 percent of China’s exports. They are the machine that has created the huge foreign-exchange reserves for Beijing and they have changed the face of these two regions. It is highly ironic that the old Treaty Ports, which once symbolized its weakness and subservience to foreign colonizers, are now the source of China’s rise as a global manufacturing and trading power, becoming in the process the most vibrant and exciting parts of the country and, indeed, of all Asia.

) companies; there is virtually no state sector remaining. These areas consistently attract 70 percent of total foreign direct investment and contribute over 70 percent of China’s exports. They are the machine that has created the huge foreign-exchange reserves for Beijing and they have changed the face of these two regions. It is highly ironic that the old Treaty Ports, which once symbolized its weakness and subservience to foreign colonizers, are now the source of China’s rise as a global manufacturing and trading power, becoming in the process the most vibrant and exciting parts of the country and, indeed, of all Asia.

FIGURE 1.4

US$818 billion accumulated FDI by province, 1993–2008

Source: China Statistical Yearbook, various

China’s economic geography is not simply based on geography. There is a parallel economy that is geographic as well as politically strategic. This is commonly referred to as the economy “inside the system” (

tizhinei ) and, from the Communist Party’s viewpoint, it is the real political economy. All of the state’s financial, material and human resources, including the policies that have opened the country to foreign investment, have been and continue to be directed at the “system.” Improving and strengthening it has been the goal of every reform effort undertaken by the Party since 1978. It must be remembered that the efforts of Zhu Rongji, perhaps China’s greatest reformer, were aimed at strengthening the economy “inside the system,” not changing it. In this sense, he is China’s Mikhail Gorbachev; he believed in the system’s capacity for change as well as the dire need for its reform. Nothing Zhu undertook was ever intended to weaken the state or the Party.

) and, from the Communist Party’s viewpoint, it is the real political economy. All of the state’s financial, material and human resources, including the policies that have opened the country to foreign investment, have been and continue to be directed at the “system.” Improving and strengthening it has been the goal of every reform effort undertaken by the Party since 1978. It must be remembered that the efforts of Zhu Rongji, perhaps China’s greatest reformer, were aimed at strengthening the economy “inside the system,” not changing it. In this sense, he is China’s Mikhail Gorbachev; he believed in the system’s capacity for change as well as the dire need for its reform. Nothing Zhu undertook was ever intended to weaken the state or the Party.

Understood in this context, the foreign and non-state sectors will be supported only as long as they are critical as a source of jobs (and hence, the all-important household savings), technology and foreign exchange. The resemblance of today’s commercial sector in China, both foreign and local, to that of merchants in traditional, Confucian China is marked: it is there to be used tactically by the Party and is not allowed to play a dominant role.

THIRTEEN YEARS OF REFORM: 1992–2005

Foreign investment has enriched certain localities and their populace beyond recognition, but foreign financial services have done far more on behalf of the Party and its system. It is not an exaggeration to say that Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley made China’s state-owned corporate sector what it is today. Without their financial know-how, SOEs would long since have lapsed into obscurity, out-competed by China’s entrepreneurs, as they were in the 1980s. In the 1980s, who could have named a single Chinese company other than Beijing Jeep, a joint venture, and, maybe, Tsingtao Beer, a brand from the colonial past? In Shenzhen, there is a huge billboard with a portrait of Deng Xiaoping located on the spot where he made his famous comments during his historic “Southern Excursion” of January 1992. If Deng had not said that capitalist tools would work in socialist hands, who knows where China would be today? His words provided the political cover for all others who, like Zhu Rongji, wanted China’s “system” to move forward into the world.

In early 1993, Zhu took the first big step forward when he accepted the suggestion of the chief executive of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange to open the door for selected SOEs to list on overseas stock markets. He knew and supported the idea that Chinese SOEs would have to undergo restructuring in line with international legal, accounting and financial requirements to achieve their listings. He hoped that foreign regulatory oversight would have a positive effect on their management performance. His expectations in many ways were met. After several years of experimentation, companies began to emerge with true economies of scale for the first time in China’s 5,000-year history.

Where did such

Fortune

Global 500 heavy-hitters as Sinopec, PetroChina, China Mobile and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China come from? The answer is simple: American investment bankers created China Mobile out of a poorly managed assortment of provincial post and telecom entities and sold the package to international fund managers as a national telecommunications giant. In October 1997, as the Asian Financial Crisis was gathering momentum, China Mobile completed a dual listing on the New York and Hong Kong stock exchanges, raising US$4.2 billion. There was no looking back as China’s oil companies, banks and insurance companies sold billions of US dollars of shares in initial public offerings (IPOs) that went off like strings of firecrackers in the global capital markets. All of these companies were imagined up, created and listed by American investment bankers.