Reflections (27 page)

Authors: Diana Wynne Jones

Characterization:

Advice for Young Writers

Â

Always ready to give suggestions and advice, Diana wrote this piece to help aspiring young writers.

Â

Â

Y

our charactersâthe people in your storyâare the most important part of what you write. They are the things that make the plot work. Things don't just happen. People

make

them happen. They do this by deciding to do one thing rather than another; by reacting to one another (“I like this person, I hate that one, this other person is a fool”); by having strong beliefs about life; by being vain or selfish; and sometimes by being feeble and not doing anything at all.

It follows that you have to find the right people for your story. It is no good, for instance, if the story you want to tell concerns someone getting to be king of the world, and you make that person feeble and timidâor, if you do, it would have to be a story about how this person got to be king by a set of accidents and misunderstandings. This would be very different from a story of a strong person forging on through all sorts of barriers, and getting to be king in the end. See what I mean? The kind of person the story happens to makes all the difference.

Some writers try to solve this matter in one of two ways: in the first, they have one main character who is a sort of stooge and observer, and have events and personalities happen in front of this person. The result is that the observer character becomes just a window for the reader to look through, with no discernible personality, and the plot is a set of disconnected episodes. What you get is a sort of variety show and not a story at all. A very

good

example of this is

Alice in Wonderland

, but it is not a method that anyone should imitate unless she/he is actually a genius.

The second way is worse: here the writer decides on a set of names (usually hard to remember) and has these names doing what the story wants them to do, without the

reason

for what they do being part of these named people at all. I think the hope here is that if you work them hard enough these cardboard figures will turn out to be real people in some way. In fact, it ends up with the reader puzzling about

why

Ertyulop ran off with the treasure, when in the last chapter he/she was trying to defend it. Or

why

Asdfgh suddenly decided to go on this quest when there was nothing in it for him/her. Or even why Oknmb abruptly starts to hate Ertyulop.

So how do you get it right?

You have to consider all the characters in your story to be

real people

. You have to get to know them, before you start, as if they were well-known friends. This applies to every single person in your story, not just those with leading roles. Look around you, at your friends, enemies, and most irritating aunts, and apply what you learn to whoever you put in your story. Each of these people will have a differently shaped body, for a start, which causes them to walk, sit, and gesture in a different way from the rest. Their hair will grow in an individual wayâand hang over their eyes, or not, when they are excited. Some people's teeth will stick out, or be false ones. Some will make gestures all the time, others will remain still. Most important of allâbecause this is what chiefly appears in a written storyâeach of them will

talk

in a different way. Listen carefully, and you will find that every single person has her/his own special rhythm when they speak. Once you know the rhythm of your character's speech and can get it written into what they say, the chances are that this character will strike readers as a real person.

The other thing about real people is that they have jobs, hobbies, and a life outside the place where you usually meet them. This is another thing that you should be careful to know about your characters. Nothing is less convincing than a person who only seems to come alive at the moments when they take part in the story. Make sure you know what they are doing when you are not actually writing about themâwhat they have for breakfast, what their outside interests are, the kind of clothes they buy. Then, even if you don't actually mention much of this, the person will have proper depth.

Knowing what each person is like offstage, so to speak, is often a great help to writing the story. Let us say, for example, you are stuck in the writing because the plot demands that your main character finds out a vital fact, and you have no idea where she/he can get it. Then, fortunately, you remember that nervous old Mr. Buggins next door has a junk shop down by the market. Your main character can drop into the shop andâbeholdâthe vital fact is there in the shop window. If you had not known this about Mr. Buggins, the story might be stuck indeed.

But take care: there is no need to go on about a character and put in all you know. This is another way to produce a cardboard effect. The fact is,

you

need to know, but the reader doesn't. Long descriptions of someone's appearance and lifestyle are a total turn-off. But if

you

know, it will come over without your having to tell it.

We come now to a thing you have to know best of all, and that is a character's inward life. Again, you do not have to go into it in detail (unless it is vital to the plot or particularly odd and interesting) but you do have to know what makes a person tick. If, for instance, you are writing about a mild and timid person, but the story requires that this person suddenly becomes fierce and bold, you have to know from the beginning that, somewhere in this person's psyche, there are the seeds of boldness. If you know that from the start, then hints of this will get dropped, and it will not seem wholly unlikely when this person suddenly rushes upon Uncle Bill and bites him in the neck. And this goes for the mind of every person you wish to portray. The kind of people they are inside gives you the

reasons

for what they do in the story.

There is a lovely bonus that comes with knowing your characters from the inside out. If you have got it right, there will come a moment when they start acting like real, independent people. They will do things and say things that even you do not expect. Let them. They will add immeasurably to the depth and excitement of your narrative.

All this applies particularly to the baddies in a story. You have to remember that villains are real people too. They have reasons for what they do, and motives for the way they behave, and they do not, as a rule, regard themselves as evil. They are acting for a cause, or out of deeply held convictions which have led them the wrong way. A lot of writers forget this. They make the baddie give evil laughs and rejoice in his/her wickednessâor worse, they wriggle out by making the villain mad. And they have the villain with no outside life except to torment the hero. The majority of bad people are not like this. It is much better to consider them as just like other people, but nasty.

And here is a tip, something I often do. Make your baddie someone you know and dislike. Use a real live person. Then there will be no trouble in making him/her convincing. You know them anyway. People are often shocked when I say this. But, since no bad person ever thinks of themselves as bad, these live people will always fail to recognize themselves and there is no harm done. Besides, they deserve it. So look around you. There must be someone bad that you know. Use them. And another bonus will be that the rest of your characters, because they are reacting to a real person, will start behaving more like real people too.

Â

This autobiography was provided for the Gale Autobiography Series

Something About the Author,

Volume 7, published in 1988.

Â

Â

I

think I write the kind of books I do because the world suddenly went mad when I was five years old. In late August 1939, on a blistering hot day, my father loaded me and my three-year-old sister, Isobel, into a friend's car and drove to my grandparents' manse in Wales. “There's going to be a war,” he explained. He went straight back to London, where my mother was expecting her third baby any day. We were left in the austere company of Mam and Dad (as we were told to call them). Dad, who was a moderator of the Welsh Nonconformist chapels, was a stately patriarch; Mam was a small, browbeaten lady who seemed to us to have no character at all. We were told that she was famous in her youth for her copper hair, her wit, and her beauty, but we saw no sign of any of this.

Wales could not have been more different from our new house in Hadley Wood on the outskirts of London. It was all gray or very green and the houses were close together and dun colored. The river ran black with coalâand probably always had, long before the mines: they told me the name of the place meant “bridge over the river with the black voice.” Above all, everybody spoke a foreign language. Sometimes we were taken up the hill into suddenly primitive country to meet wild-looking, raw-faced old people who spoke no English, for whom our shy remarks had to be translated. Everyone spoke English to us, and would switch abruptly to Welsh when they wanted to say important things to one another. They were kind to us, but not loving. We were Aneurin's English daughters and not quite part of their culture.

Â

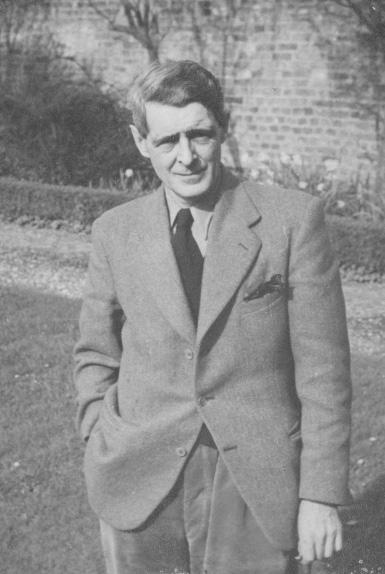

Diana's father, Aneurin Jones, 1952

Â

Life in the manse revolved around the chapel next door. My aunt Muriel rushed in from her house down the road and energetically took us to a dressmaker to be fitted with Sunday clothes. On the way, she suggested that, to stop us feeling strange, we should call her “Mummy.” Isobel obligingly did so, but I refused on the grounds that she was not our motherâbesides, I was preoccupied with a confusion between dressmakers and hairdressers which even an hour of measuring and pinning did not resolve.

The clothes duly arrived: purple dresses with white polka dots and neat meat-colored coats. Isobel and I had never been dressed the same before and we rather liked it. We wore them to chapel thereafter, sitting sedately with our aunt and almost grown-up cousin Gwyn, through hours of solid Welsh and full-throated singing. Isobel sang too, the only Welsh she knew, which happened to be the name of the maid at the manse, Gwyneth. My mother had told me sternly that I was bad at singing and, not knowing the words, I couldn't join in anyway. Instead, I gazed wistfully at the shiny cherries on the hat of the lady in front, and one Sunday got into terrible trouble for daring to reach out and touch them.

Â

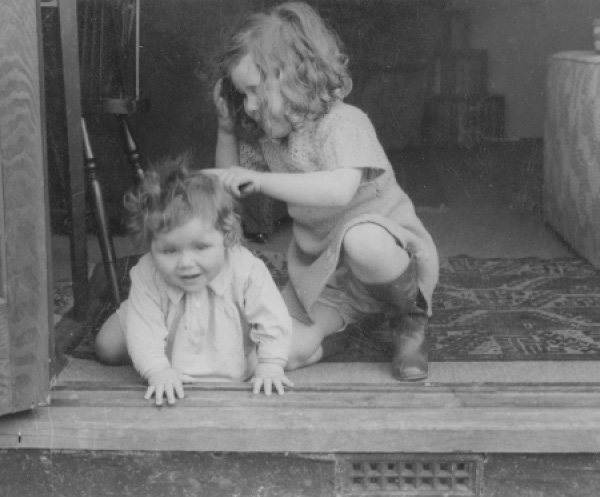

Diana brushing her sister Isobel's hair, 1937

Â

Then my grandfather went into the pulpit. At home he was majestic enough: preaching, he was like the prophet Isaiah. He spread his arms and language rolled from him, sonorous, magnificent, and rhythmic. I had no idea then that he was a famous preacher, nor that people came from forty miles away to hear him because he had an almost bardic tendency to speak a kind of blank verseâ

hwyl

, it is called, much valued in a preacherâbut the splendor and the rigor of it nevertheless went into the core of my being. Though I never understood one word, I grasped the essence of a dour, exacting, and curiously magnificent religion. His voice shot me full of terrors. For years after that, I used to dream regularly that a piece of my bedroom wall slid aside, revealing my grandfather declaiming in Welsh, and I knew he was declaiming about my sins. I still sometimes dream in Welsh, without understanding a word. And at the bottom of my mind there is always a flow of spoken language that is not English, rolling in majestic paragraphs and resounding with splendid polysyllables. I listen to it like music when I write.

Weekdays I was sent to the local school, where everyone was taught in Welsh except me. I was the only one in the class who could read. When the school inspector paid a surprise visit, the teacher thrust a Welsh book at me and told me in a panicky whisper to read it aloud. I did soâWelsh, luckily, is spelled phoneticallyâand I still understood not a word. When girls came to play, they spoke English too, initiating me into mysterious rhymes:

Whistle while you work, Hitler made a shirt

. War had been declared, but I had never heard of Hitler till then. We usually played in the chapel graveyard where I thought of the graves as like magnificent double beds for dead people. I fell off the manse wall into such a grave as I declaimed, “Goebbels wore it, Goering tore it,” and tore a ligament in one ankle.

After what seemed a long time, my mother arrived with our new sister, Ursula. She was outraged to find Isobel calling Aunt Muriel “Mummy.” I remember trying to soothe her by explaining that Isobel was in no way deceived: she was just obliging our aunt. Unfortunately the voice I explained in had acquired a strong Welsh accent, which angered my mother further. We felt the strain of the resulting hidden rows as an added bleakness in the bleak manse. We were back in Hadley Wood by Christmas.

Looking back, I see that my relationship with my mother never recovered from this. When she arrived in Wales, she had seen me as something other, which she rather disliked. She said I would grow up just like my aunt, and accused me of taking my aunt's side. It did not help that, at that time, my hair was just passing from blond to a color my mother called mouse, and I looked very little like either side of the family. My parents were both short, black haired, and handsome, whereas I was tall and blue-eyed. When we got back to London, my mother resisted all my attempts to hug her on the grounds that I was too big.

Meanwhile, the threat of bombing and invasion grew. London was not safe. The small school Isobel and I were attending rented a house called Lane Head beside Coniston Water in distant Westmorland, and offered a room in it to my mother and her three children. We went there in the early summer of 1940. Here were real mountains, lakes, brooks racing through indescribable greenness. I was amazedâintoxicatedâwith the beauty of it.

We were told that Lane Head had belonged to John Ruskin's secretary and that this man's descendants (now safely in America) had been the John, Susan, Titty, and Roger of Arthur Ransome's books. Ruskin's own house, Brantwood, was just up the road. There was a lady in a cottage near it who could call red squirrels from the trees. This meant more to me at the timeâthis, and the wonder of living in a rambling old house smelling of lamp oil, with no electricity, where the lounge (where we were forbidden to play) was full of Oriental trophies, silk couches, and Pre-Raphaelite pictures. There was a loft (also forbidden) packed with Titty and Roger's old toys. The entry to it was above our room and I used to sneak up into it. There were no new toys and no paper to draw on and I loved drawing. One rainy afternoon, poking about the loft, I came upon a stack of high-quality thick drawing paper. To my irritation, someone had drawn flowers on every sheet, very fine and black and accurate, and signed them with a monogram, JR. I took the monogram for a bad drawing of a mosquito and assumed the fine black pencil was ink. I carried a wad of them down to our room and knelt at the window seat industriously erasing the drawings with an ink rubber. Halfway through I was caught and punished. The loft was padlocked. Oddly enough, it was only many years later that I realized that I must have innocently rubbed out a good fifty of Ruskin's famous flower drawings.

The school and its pupils left the place toward the end of summer, but we stayed and were rapidly joined by numbers of mothers with small children. The world was madder than ever. I was told about the small boats going to Dunkirk and exasperated everyone by failing to understand why the Coniston steamer had not gone to France from the landlocked lake. (I was always asking questions.) Bombs were dropping and the Battle of Britain was escalating. My husband, who had, oddly enough, been sent to his grandparents barely fifteen miles from us, remembers the docks at Barrow-in-Furness being bombed. He saw the blaze across the bay. During that raid a German plane was shot down and its pilot was at large in the mountains for nearly two weeks. It is hard now to imagine the horror he inspired in all the mothers. When he broke into the Lane Head pantry one night and stole a large cheese, there was sheer panic the next morning. I suppose it was because that night the war had briefly climbed in through our window.

Being too young to understand this, I had trouble distinguishing Germans from germs, which seemed to inspire the mothers with equal horror. When a large Quaker family arrived to cram into the house too, bringing with them an eleven-year-old German-Jewish boy who told horrendous stories of what the police didâthey took you away in the night, he said, to torture youâI had no idea he was talking about the Gestapo. I have been nervous of policemen ever since.

The Quaker family, all six of them, had a cold bath every morning. We were regularly woken at 6:06 a.m. by the screams of the youngest, who was only two. In their no-nonsense Quaker way, this family got out the old boat from the boathouse and went sailing. I can truthfully say that I sailed in both the

Swallow

and the

Amazon

, for though this boat was a dire old tub called

Mavis

, she was the original of both. I didn't like her. On a trip to Wild Cat Island

1

I caught my finger in her centerboard, and my father nearly drowned us in her trying to sail in a storm on one of his rare visits from teaching and fire watching in London.

The mothers gave the older children lessons. Girls were taught womanly accomplishments. Being left-handed, I had great trouble learning to knit until a transient Icelandic lady arrived with a baby and a large dog and began teaching me the continental method. She left before teaching me to purl or even to cast on stitches. I had to make those up. Another mother taught sewing. I remember wrestling for a whole morning to sew on a button, which became inexplicably enmeshed in my entire supply of thread. Finally I explained to this mother that I wasn't going to grow up to be a woman, and asked if I could do drawing with the boys. She told me not to be rude and became so angry thatâwith a queer feeling that it was in self-defenseâI put my tongue out at her. She gave me a good shaking and ordered me to stand in the hall all the next morning.

The same day, other mothers had taken the younger children to the lake shore to play beyond the cottage of the lady who called squirrels. The noise the children made disturbed the occupant of the houseboat out in the bay. He came rowing angrily across and ordered them off, and, on finding where they lived, said that he wasn't going to be disturbed by a parcel of evacuees and announced that he would come next morning to complain. He hated children. There was huge dismay among the mothers. Next morning I stood in the hall, watching them rush about trying to find coffee and biscuits (which were nearly unobtainable by then) with which to soothe the great Arthur Ransome, and gathered I was about to set eyes on a real writer. I watched with great interest as a tubby man with a beard stamped past, obviously in a great fury, and almost immediately stormed away again on finding there was nobody exactly in charge to complain to. I was very impressed to find he was real. Up to then I had thought books were made by machines in the back room of Woolworth's.

My brush with the other writer in the area was even less direct but no more pleasant. We were at Near Sawrey, which was a long way for children to walk, but, if the mothers were to go anywhere, they had to walk and the children had to walk with them. No one had a car. Isobel and another four-year-old girl were so tired that, when they found a nice gate, they hooked their feet on it and had a restful swing. An old woman with a sack over her shoulders stormed out of the house and hit both of them for swinging on her gate. This was Beatrix Potter. She hated children, too. I remember the two of them running back to us, bawling with shock. Fate, I always think, seemed determined to thrust a very odd view of authorship on me.