Reflections (31 page)

Authors: Diana Wynne Jones

In 1966 we moved briefly to a cold, cold farmhouse in Eynsham while we waited for my husband's college, Jesus College, to have a house built that we could rent. There Colin started having febrile convulsions and almost everything else went wrong too. I wrote

Changeover

, my only published adult novel,

2

to counteract the general awfulness.

In 1967, the new house was ready. It had a roof that was soluble in water, toilets that boiled periodically, rising damp, a south-facing window in the food cupboard, and any number of other peculiarities. So much for my wish for a quiet life. We lived there, contending with electric fountains in the living room, cardboard doors, and so forth, until 1976, except for 1968â9, which year we spent in America, at Yale. Yale, like Oxford, was full of people who thought far too well of themselves, lived very formally, and regarded the wives of academics as second-class citizens; but America, round the edges of it, I loved. I try to go back as often as I can. We went for a glorious time to Maine, and also visited the West Indian island of Nevis, where, to my astonishment, a number of people greeted me warmly, saying, “I'm so glad you've come back!” I still don't know who they thought I was. But an old man on a donkey thought John was a ghost.

Â

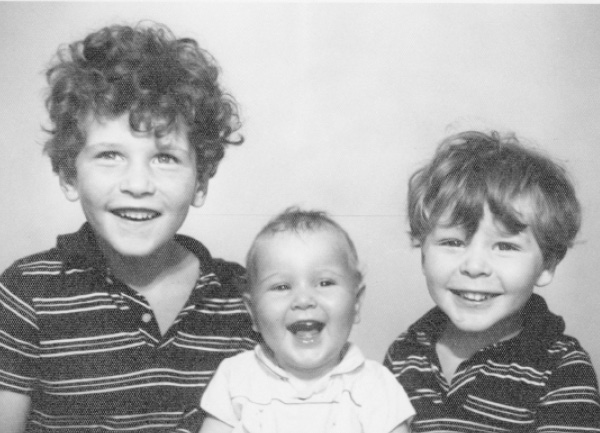

Diana's three sonsâRichard, Colin, and Michael, 1964

Â

On our return, now all the children were at school, I started writing in earnest. A former pupil of John's introduced me to Laura Cecil, who was just starting as a literary agent for children's books. She became an instant firm friend. With her encouragement, I wrote

Wilkins' Tooth

in 1972,

Eight Days of Luke

in 1973, and

The Ogre Downstairs

the same year. I laughed so much writing that one that the boys kept putting their heads round the door to ask if I was all right.

Power of Three

came after that, then

Cart and Cwidder

, followed by

Dogsbody

, though they were not published in that order.

Charmed Life

and

Drowned Ammet

were both written in 1975.

Also on our return, we acquired a cottage in West Ilsley, Berkshire, as a refuge from the defects of the Oxford house. The chalk hills there, full of racehorses, filled my head with new things to write. It was at this cottage that John was formally asked to apply for the English professorship at Bristol University. He did so, and got the job. We moved here in 1976 and were involved in a nightmare car crash the following month. Despite this, I love Bristol. I love its hills, its gorge and harbors, its mad mixture of old and new, its friendly people, and even its constant rain. We have lived here ever since. All my other books have been written here; for although the car crash, followed by my astonishment at winning the 1978

Guardian

Children's Fiction Prize, almost stopped me dead between them, I get unhappy if I don't write. Each book is an experiment, an attempt to write the ideal book, the book my children would like, the book I

didn't

have as a child myself.

I have still not, after twenty-odd books, written that book. But I keep trying. Nor do I manage to live a quiet life. I keep undertaking things, like visiting schools and teaching courses as a writer, or learning the cello, or doing amateur theatricals, or rashly agreeing to do all the cooking for Richard's wedding in 1984. Every one of those things has led to comic disastersâexcept the wedding: that was perfect. My aunt Muriel came to it just before she died, wearing a mink headdress like a cardinal's hat, and gave the couple her blessing. My mother also came. She was widowed again in 1975 and keeps on cordial terms with the rest of her family. She thinks John is marvelous.

Another thing that stops me living a quiet life is my travel jinx. This is hereditary: my mother has it and so does my son Colin. Mine works mostly on trains. Usually the engine breaks, but once an old man jumped off a moving train I was on and sent every train schedule in the country haywire for that day. And my books have developed an uncanny way of coming true. The most startling example of this was last year, when I was writing the end of

A Tale of Time City

. At the very moment when I was writing about all the buildings in Time City falling down, the roof of my study fell in, leaving most of it open to the sky.

Perhaps I don't need a quiet life as much as I think I do.

Â

Diana with her faithful dog Caspian, who inspired

Dogsbody

, 1984

Â

Â

A humorous autobiographical anecdote, this story was previously published in

Sisters

, edited by Miriam Hodgson (Mammoth, 1998) and in Diana's collection

Unexpected Magic

(Greenwillow, 2004).

Â

Â

I

t was 1944. I was nine years old and fairly new to the village. They called me “the girl Jones.” They called anyone “the girl this” or “the boy that” if they wanted to talk about them a lot. Neither of my sisters was ever called “the girl Jones.” They were never notorious.

On this particular Saturday morning I was waiting in our yard with my sister Ursula because a girl called Jean had promised to come and play. My sister Isobel was also hanging around. She was not exactly with us, but I was the one she came to if anything went wrong and she liked to keep in touch. I had only met Jean at school before. I was thinking that she was going to be pretty fed up to find we were lumbered with two little ones.

When Jean turned up, rather late, she was accompanied by two little sisters, a five-year-old very like herself and a tiny three-year-old called Ellen. Ellen had white hair and a little brown stormy face with an expression on it that said she was going to bite anyone who gave her any trouble. She was alarming. All three girls were dressed in impeccable starched cotton frocks that made me feel rather shabby. I had dressed for the weekend. But then so had they, in a different way.

“Mum says I got to look after them,” Jean told me dismally. “Can you have them for me for a bit while I do her shopping? Then we can play.”

I looked at stormy Ellen with apprehension. “I'm not very good at looking after little ones,” I said.

“Oh, go on!” Jean begged me. “I'll be much quicker without them. I'll be your friend if you do.”

So far, Jean had shown a desire to play, but had never offered friendship. I gave in. Jean departed, merrily swinging her shopping bag.

Almost at once a girl called Eva turned up. She was an official friend. She wore special boots and one of her feet was just a sort of blob. Eva fascinated me, not because of the foot but because she was so proud of it. She used to recite the list of all her other relatives who had queer feet, ending with, “And my uncle has only one toe.” She too carried a shopping bag and had a small one in tow, a brother in her case, a wicked five-year-old called Terry. “Let me dump him on you while I do the shopping,” Eva bargained, “and then we can play. I won't be long.”

“I don't know about looking after boys,” I protested. But Eva was a friend and I agreed. Terry was left standing beside stormy Ellen, and Eva went away.

A girl I did not know so well, called Sybil, arrived next. She wore a fine blue cotton dress with a white pattern and was hauling along two small sisters, equally finely dressed. “Have these for me while I do the shopping and I'll be your friend.” She was followed by a rather older girl called Cathy, with a sister, and then a number of girls I only knew by sight. Each of them led a small sister or brother into our yard. News gets round in no time in a village. “What have you done with your sisters, Jean?” “Dumped them on the girl Jones.” Some of these later arrivals were quite frank about it.

“I heard you're having children. Have these for me while I go down the rec.”

“I'm not good at looking after children,” I claimed each time before I gave in. I remember thinking this was rather odd of me. I had been in sole charge of Isobel for years. As soon as Ursula was four, she was in my charge too. I suppose I had by then realized I was being had for a sucker, and this was my way of warning all these older sisters. But I believed what I said. I was not good at looking after little ones.

In less than twenty minutes I was standing in the yard surrounded by small children. I never counted, but there were certainly more than ten of them. None of them came above my waist. They were all beautifully dressed because they all came from what were called the “clean families.” The “dirty families” were the ones where the boys wore big black boots with metal in the soles and the girls had grubby frocks that were too long for them. These kids had starched creases in their clothes and clean socks and shiny shoes. But they were, all the same, skinny, knowing, village children. They knew their sisters had shamelessly dumped them and they were disposed to riot.

“Stop all that damned

noise

!” bellowed my father. “Get these children out of here!”

He was always angry. This sounded near to an explosion.

“We're going for a walk,” I told the milling children. “Come along.” And I said to Isobel, “Coming?”

She hovered away backward. “No.” Isobel had a perfect instinct for this kind of thing. Some of my earliest memories are of Isobel's sturdy brown legs flashing round and round as she rode her bicycle for dear life away from a situation I had got her into. These days, she usually arranged things so that she had no need to run for her life. I was annoyed. I could have done with her help with all these kids. But not that annoyed. Her reaction told me that something interesting was going to happen.

“We're going to have an adventure,” I told the children.

“There's no adventures nowadays,” they told me. They were, as I said, knowing children, and no one, not even me, regarded the war that was at that time going on around us as any kind of adventure. This was a problem to me. I craved adventures of the sort people had in books, but nothing that had ever happened to me seemed to qualify. No spies made themselves available to be unmasked by me, no gangsters ever had nefarious dealings where I could catch them for the police.

But one did what one could. I led the crowd of them out into the street, feeling a little like the Pied Piperâor no: they were so little and I was so big that I felt really old, twenty at least, and rather like a nursery school teacher. And it seemed to me that since I was landed in this position I might as well do something I wanted to do.

“Where are we going?” they clamored at me.

“Down Water Lane,” I said. Water Lane, being almost the only unpaved road in the area, fascinated me. It was like lanes in books. If anywhere led to adventure, it would be Water Lane. It was a moist, mild, gray day, not adventurous weather, but I knew from books that the most unlikely conditions sometimes led to great things.

But my charges were not happy about this. “It's wet there. We'll get all muddy. My mum told me to keep my clothes clean,” they said from all around me.

“You won't get muddy with me,” I told them firmly. “We're only going as far as the elephants.” There was a man who built life-sized mechanical elephants in a shed in Water Lane. These fascinated everyone. The children gave up objecting at once. Ellen actually put her hand trustingly in mine, and we crossed the main road like a great liner escorted by coracles.

Water Lane was indeed muddy. Wetness oozed up from its sandy surface and ran in dozens of streams across it. Mr. Hinkston's herd of cows had added their contributions. The children minced and yelled. “Walk along the very edge,” I commanded them. “Be adventurous. If we're lucky, we'll get inside the yard and look at the elephants in the sheds.”

Most of them obeyed me except Ursula. But she was my sister and I had charge of her shoes along with the rest of her. Although I was determined from the outset to treat her exactly like the other children, as if this was truly a class from a nursery school, or the Pied Piper leading the children of Hamelin Town, I decided to let her be. Ursula had times when she bit you if you crossed her. Besides, what were shoes? So, to cries of, “Ooh! Your sister's getting in all the pancakes!” we arrived outside the big black fence where the elephants were, to find it all locked and bolted. As this was a Saturday, the man who made the elephants had gone to make money with them at a fête or a fair somewhere.

There were loud cries of disappointment and derision at this, particularly from Terry, who was a very outspoken child. I looked up at the tall fenceâit had barbed wire along the topâand contemplated boosting them all over it for an adventure inside. But there were their clothes to consider, it would be hard work, and it was not really what I had come down Water Lane to do.

“This means we have to go on,” I told them, “to the really adventurous thing. We are going to the very end of Water Lane to see what's at the end of it.”

“That's ever so far!” one of them whined.

“No, it's not,” I said, not having the least idea. I had never had time to go much beyond the river. “Or we'll get to the river and then walk along it to see where it goes to.”

“Rivers don't go anywhere,” someone pronounced.

“Yes, they do,” I asserted. “There's a bubbling fountain somewhere where it runs out of the ground. We're going to find it.” I had been reading books about the source of the Nile, I think.

They liked the idea of the fountain. We went on. The cows had not been on this farther part, but it was still wet. I encouraged them to step from sandy strip to sandy island, and they liked that. They were all beginning to think of themselves as true adventurers. But Ursula, no doubt wanting to preserve her special status, walked straight through everything and got her shoes all wet and crusty. A number of the children drew my attention to this.

“She's not good like you are,” I said.

We went on in fine style for a good quarter of a mile until we came to the place where the river broke out of the hedge and swilled across the lane in a ford. Here the expedition broke down utterly.

“It's water! I'll get wet! It's all muddy!”

“I'm

tired

!” said someone. Ellen stood by the river and grizzled, reflecting the general mood.

“This is where we can leave the lane and go up along the river,” I said. But this found no favor. The banks would be muddy. We would have to get through the hedge. They would tear their clothes.

I was shocked and disgusted at their lack of spirit. The ford across the road had always struck me as the nearest and most romantic thing to a proper adventure. I loved the way the bright brown water ran so continuously thereâin the mysterious way of riversâin the shallow sandy dip.

“We're going on,” I announced. “Take your shoes off and walk through in your bare feet.”

This, for some reason, struck them all as highly adventurous. Shoes and socks were carefully removed. The quickest splashed into the water. “Ooh! Innit

cold

!”

“I'm paddling!” shouted Terry. “I'm going for a paddle.” His feet, I was interested to see, were perfect. He must have felt rather left out in Eva's family.

I lost control of the expedition in this moment of inattention. Suddenly everyone was going in for a paddle. “All right,” I said hastily. “We'll stay here and paddle.”

Ursula, always fiercely loyal in her own way, walked out of the river and sat down to take her shoes off too. The rest splashed and screamed. Terry began throwing water about. Quite a number of them squatted down at the edge of the water and scooped up muddy sand. Brown stains began climbing up crisp cotton frocks; the seats of beautifully ironed shorts quickly acquired a black splotch. Even before this was pointed out to me, I saw this would not do. These were the “clean children.” I made all the little girls come out of the water and spent some time trying to get the edges of their frocks tucked upward into their knickers. “The boys can take their trousers off,” I announced.

But this did no good. The frocks just came tumbling down again and the boys' little white pants were no longer really white. No one paid any attention to my suggestion that it was time to go home now. The urge to paddle was upon them all.

“All right,” I said, yielding to the inevitable. “Then you all have to take all your clothes off.”

This caused the startled pause. “That ain't right,” someone said uncertainly.

“Yes it is,” I told them, somewhat pompously. “There is nothing whatsoever wrong with the sight of the naked human body.” I had read that somewhere and found it quite convincing. “Besides,” I added, more pragmatically, “you'll all get into trouble if you come home with dirty clothes.”

That all but convinced them. The thought of what their mums would say was a powerful aid to nudity. “But won't we catch cold?” someone asked.

“Cavemen never wore clothes and they never caught cold,” I informed them. “Besides, it's quite warm now.” A mild and misty sunlight suddenly arrived and helped my cause. The brown river was flecked with sun and looked truly inviting. Without a word, everybody began undressing, even Ellen, who was quite good at it, considering how young she was. Back to nursery teacher mode again, I made folded piles of every person's clothing, shoes underneath, and put them in a large row along the bank under the hedge. True to my earlier resolve, I made no exception for Ursula's clothes, although her dress was an awful one my mother had made out of old curtains, and thoroughly wet anyway.

There was a happy scramble into the water, mostly to the slightly deeper end by the hedge. Terry was throwing water instantly. But then there was another pause.

“

You

undress too.” They were all saying it.

“I'm too big,” I said.

“You

said

that didn't matter,” Ursula pointed out. “You undress too, or it isn't

fair

.”

“Yeah,” the rest chorused. “It ain't

fair

!”

I prided myself on my fairness, and on my rational, intellectual approach to life, but . . .

“Or we'll all get dressed again,” added Ursula.

The thought of all that trouble wasted was too much. “All right,” I said. I went over to the hedge and took off my battered gray shorts and my old, pulled jersey and put them in a heap at the end of the row. I knew as I did so why the rest had been so doubtful. I had never been naked out of doors before. In those days, nobody ever was. I felt shamed and rather wicked. And I was so big, compared with the others. The fact that we all now had no clothes on seemed to make my size much more obvious. I felt like one of the man's mechanical elephants, and sinful with it. But I told myself sternly that we were having a rational adventurous experience, and joined the rest in the river.