Replay: The History of Video Games (21 page)

Read Replay: The History of Video Games Online

Authors: Tristan Donovan

Ideas spilled forward. Players could trade goods between space stations in different parts of the universe or carry out odd jobs or earn bounties from killing space pirates or mine asteroids for minerals. “The idea of score equals money seemed utterly logical, especially as we had settled on trading as the way the player was grounded in the game,” said Braben. “Very quickly we contextualised the additional sources of money – so the reward for shooting a ship became bounty and so on. This was at the time of the Miner’s Strike and somehow a dog-eat-dog mentality for the game felt appropriate.”

The idea of being a space-age trucker had already been explored by a few trading games, such as 1974’s

Star Traders

– a text game for mainframe computers – and 1980’s

Galactic Trader

on the Apple II, but neither Bell and Braben knew of their existence. “To my knowledge there were no space trading games. The main way games influenced me, at least, was in terms of what I didn’t want in a game,” said Braben. “I felt games had got into a bit of a rut, always with three lives, a score that went up in 10s with a free life at 10,000 and a play time aimed at 10 minutes or so. I strongly felt games didn’t have to be that way. There were some text adventure games with a much longer play life and a story and this contrast showed other approaches were possible.”

Bell and Braben spent two years making

Elite

in-between their university studies, perfecting the game’s mix of combat, moneymaking, ship-upgrading and intergalactic trading to create a game where players could make their own way and decide their own priorities. The player began the game with 100 credits and a basic spacecraft but from then on the universe was their oyster. They could be a hero, a space pirate, a miner, an entrepreneur, a gun for hire or simply head out into the void and explore the stars.

Elite

’s world in a box opened up a new avenue for game designers to explore: the concept of open-ended worlds where players decide what to do and where to go, rather than being required to complete pre-decided goals in worlds that restricted their choices.

Elite

,

Knight Lore

,

Deus Ex Machina

and

Jet Set Willy

typified the atmosphere of creativity and opportunity that powered the early UK games industry, which for most of the early 1980s was still an unstructured cottage industry. “People could afford to take risks, the barriers to entry were really low,” said Penn. “Literally anyone in their bedroom who had half a brain and some passion could make something and get it in the hands of people. There was a lot of inventiveness, not all of it necessarily good. That was part of the joy of being around in that period – the amount of innovation that was going on was quite something.”

The energy of the UK market at this time also encouraged the growth of video game industries in Spain and Australia.

Spain had also embraced the ZX Spectrum, exposing the Spanish to many of the games being released in the UK while giving the Iberian nation’s ambitious game companies the chance to sell their work to the much larger pool of British players. For companies like Madrid’s Dinamic, the UK game business showed the way forward. “Imagine and Ocean were our idols,” said co-founder Victor Ruiz, referring to the UK’s two biggest game publishers around the time of Dinamic’s formation in 1984. Dinamic and rivals such as Opera Soft and Indescomp would make Spain a leader in European game development in the 1980s, thanks to visually impressive games such as the

Rambo

-inspired

Army Moves

and the bank-robbing action game

Goody

. Looks were a big focus for many Spanish games.

“The visuals and graphic effects are very important in video games and we paid special attention to them,” said Pedro Ruiz, the director of Opera Soft. “At the end of the day, a video game is a visual experience and some spectacular graphics can make up for a game that is not particularly good. We wanted to develop games that got people hooked and were hard to play – sometimes too hard – and to use the latest technologies available at the time.”

The high point for Spanish games in the 1980s was Paco Menéndez’s

Knight Lore

-inspired

La Abadía del Crimen

, which Opera Soft published in 1988. “It was inspired by a novel, Umberto Eco’s

The Name of the Rose

. We got in contact with the writer so we could give the game the same name as the novel, but received no reply. This is why we changed the title,” said Pedro Ruiz. “It was not an arcade-type game of skill, but a game of intelligence.” Set in a medieval monastery, the player takes the role of a Franciscan monk who must solve a series of murders while carrying out religious duties. “The game was special both in terms of the result and how it was made,” said fellow Opera Soft employee Gonzalo Suárez, who left the Spanish movie business to make games starting with 1987’s

Goody.

“

La Abadía del Crimen

was a graphic adventure but with a freedom of movement unknown until that time with a recreation of the abbey in isometric graphics that far outstripped the production kings of the time like Ultimate.” Never released outside Spain,

La Abadía del Crimen

was a commercial disappointment that only achieved the recognition it deserved years later.

The UK market also proved crucial to Australia. Having watched the rise of the ZX80, Milgrom and his wife Naomi Besen returned to their native Australia in December 1980 with a plan to start Beam Software, a business that would create games for the UK market that Melbourne House would publish. “At the very beginning the idea was not to develop software, but rather to develop content for computer books,” said Milgrom. “Then one day I thought more about the concept of publishing and I realised that there was very little difference between developing material and putting that content onto paper or onto a cassette tape.”

Beam Software became the focal point for the Australian game industry. It recruited graduates from the Univers

ity of Melbourne’s computing courses and rapidly expanded off the back of hits such as its million-selling text adventure remake of J.R.R. Tolkien’s

The Hobbit

.

[3]

Soon almost every would-be game developer in Australia was moving to Melbourne to join the swelling ranks of Beam Software. “We were doubling in staff every year for almost eight years. Every three years we had to move offices,” said Milgrom. “People from all over Australia would write to us and come over for interviews. You have to understand we were offering people a job. In the UK a lot of people were doing it as a hobby, but you couldn’t do that from Australia because there was no means of distribution. You couldn’t just expect your games to be sold as there’s no major market in Australia. They could move over to the UK, but it made a lot more sense to come and work for us.”

Off the back of Beam Software’s hit games, Melbourne House ditched book publishing and became one of the UK’s largest game publishers of the 1980s. The talent that built Beam would go on to create the bulk of the Australian games industry. “One of the things I am especially proud of is that Beam effectively started the games industry in Australia,” said Milgrom. “Almost all of the development studios in Australia since then were started by ex-Beam employees or have been substantially staffed by ex-Beam employees.”

Powered by Sinclair’s cheap computers, the UK’s bedroom programmers had turned their country into a hotbed of experimental game design, inspired developers in Spain and laid the foundations for the Australian industry at the same time. But the UK was not the only European country forging new ground in video games.

[

1

]. Europe’s console manufacturers, however, rapidly lost ground to US-designed consoles after the arrival of the Philips Videopac G7000 the following year. The G7000, the European name for the Magnavox Odyssey

2

, proved almost as popular as the Atari VCS 2600 in Europe.

[

2

]. The ZX80 used cassettes to store and load programs. While the US was already starting to move away from cassette storage by the early 1980s, computers withk drives were rare in the UK until the latter half of the decade, mainly due to cost.

[

3

].

The Hobbit

introduced several new concepts to text adventures, including characters that would carry out actions and make decisions independently of the player, a marked change from the usually static worlds of these games. It also assigned physical properties to the various objects in the game. “The puzzles were based on using those properties,” said Milgrom. “But it also meant that some totally unintended things could be done by the players because the physics of the environment allowed it to happen, such as tricking Thorin to get in the chest and locking him in.”

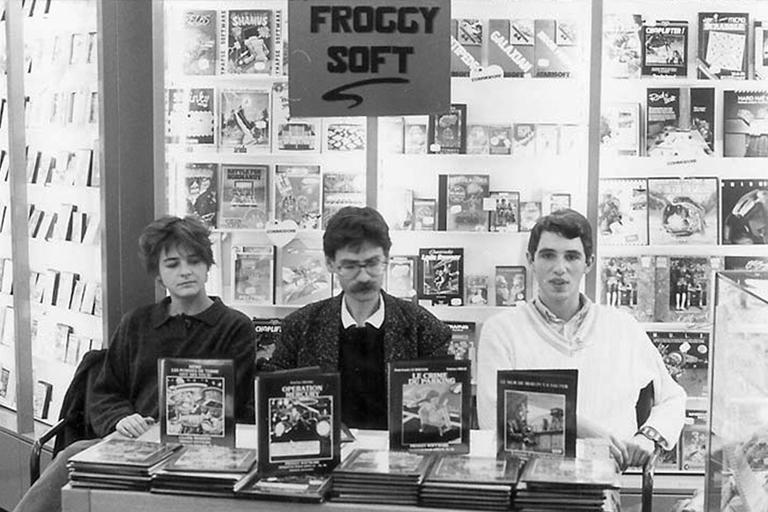

Froggy Software: (left to right) Clotilde Marion, Jean-Louis Le Breton and Tristan Cazenave. Courtesy of Jean-Louis Le Breton

10. The French Touch

Paris was a war zone. Egged on by the Vietnam War and the rebellious rhetoric of the Situationist International, t

housands marched on the city streets demanding revolution.

[1]

They spray painted slogans onto the city’s walls: ‘DEMAND THE IMPOSSIBLE’, ‘IMAGINATION IS SEIZING POWER’, ‘MAKE LOVE, NOT WAR’ and ‘BOREDOM IS COUNTER-REVOLUNTIONARY’.

They constructed makeshift barricades out of parked cars and started fires. They battled with France’s quasi-military riot police, the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité, which sought to suppress the uprising with tear gas and beatings with batons. The protestors responded by hurling bottles, bricks and paving stones ripped up from the streets. France’s trade unions sided with the protestors and encouraged wildcat strikes across the nation in a show of solidarity. The government had lost control and France teetered on the brink of revolution. For a few days in May 1968 it looked as if the motley coalition of students, trade unions, Trotskyites, anti-capitalists, situationists, anarchists and Maoists would win their fight for revolution. Ultimately they did not. In early June, the protests died out thanks to a combination of government capitulation and renewed crackdowns on the protestors.

But the failed revolution inspired many. Among them was Jean-Louis Le Breton, a Parisian teenager whose worldview was shaped by the idealism of the revolutionaries who took to the streets that May. “I was 16 in ’68 and part of the protests in Paris,” he said. “I spent most of my time in the Latin Quarter with other students. Our teachers were on strike and we had a lot of discussions. We thought we could change the world. It was both a period of political consciousness and of utopia. We used to mix flower power with throwing cobblestones at policemen. Many things changed after ’68: women could wear trousers, radios and TV felt more free and able to criticise the government.” During the late 1970s and early 1980s Le Breton explored his desire to challenge the status quo via music. He experimented with synthesizers in his band Dicotylédon before delving into avant-garde rock ’n’ roll wth another act, Los Gonococcos. Then in 1982 he found a new outlet. “Los Gonococcos split in 1982 and I exchanged my synthesizers for the first Apple computer delivered in France, the Apple II,” he said. “At that time, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were presented as two guys working in their garage – such a pleasant image in opposition with IBM. I found that programming in BASIC was easy and fun and I could imagine a lot of amusements with this fascinating machine. It was possible to take power over computers and bring them into the mad galaxy of my young and open mind.”

Le Breton had played video games before but didn’t like them: “I’ve never been interested in playing games. The first game I played was a game that took place in Egypt – I don’t remember the title. I was interested by the fact that you could move the character, but it was no fun. Too many fights. Not for me.” But after playing Sierra’s illustrated text adventure

Mystery House

, he decided to write a game of his own. “The graphics and scenario of

Mystery House

were such bad quality that I thought I could easily produce the same kind of game,” he said. The result was 1983’s

Le Vampire Fou

, the first text adventure written in French. “You had to enter the castle of Le Vampire to kill him before he killed you,” said Breton. “It was the kind of game that made you crazy before you could find the right answer.”

Le Breton earned nothing from

Le Vampire Fou

. Its publisher Ciel Bleu – an importer of Canadian educational software – went bust shortly after its release. With Ciel Bleu gone, Le Breton teamed up with his friend Fabrice Gille in 1984 to form his own game publishing company Froggy Software, which summed up the essence of its games as ‘aventure, humour, décalage et déconnade’.

[2]

From their base in Le Breton’s home, an old bar in the 20th district of Paris, the pair dreamed big. “We felt both like modern young people and artisans. The ideas of the games came out of our brains and were directly translated into the computer. I was personally happy to use the computer in a literary way. I thought we should not let computers be only in engineers’ hands,” said Le Breton. The spirit of May 1968 lurked within Froggy’s DNA. “May 1968 surely had an influence on the way we started the company, with a completely free and open state of mind and a bit of craziness. We wanted to change the mentalities, the old-fashioned way of thinking. Humour, politics and new technologies seemed to be an interesting way to spread our state of mind,” said Le Breton. Almost all of Froggy’s games were text adventures, but with their humour and political themes they were a world away from the fantasy and sci-fi tales that typified the genre in the UK and US.

Même les Pommes de Terre ont des Yeux

offered a comic take on South American revolutionary politics.

La Souris Golote

revelled in puns about cheese. The sordid murder mystery of

Le Crime du Parking

touched on rape, drug addiction and homosexuality while

Paranoïak

had players battling against their character’s smorgasbord of mental illnesses. Le Breton’s efforts prompted French games magazine

Le Breton and Gille were not the only French game designers taking games in a more highbrow and consciously artistic direction. Muriel Tramis, an African-Caribbean woman who grew up on the French-Caribbean island of Martinique, was also exploring the medium’s potential. She left Martinique for France in the 1970s to study engineering at university and, after several years working in the aerospace industry, became interested in the potential of video games and joined Parisian game publisher Coktel Vision. She decided her own heritage should be the subject of her debut game

Méwilo

, an 1987 adventure game written with help from another former Martinique resident Patrick Chamoiseau, one of the founding figures of the black literary movement Créolité. “The game was inspired by the Carib legend of jars of gold,” explained Tramis. “At the height of the slave revolts, plantation masters saved their gold in the worst way. They got their most faithful slave to dig a hole and then killed and buried him with the gold in order that the ghost of the unfortunate slave would keep the curious away from the treasure.”

In the game the player took on the role of Méwilo, a parapsychologist who travels to the Martinique city of Saint-Pierre in 1902 to investigate reports of a haunting, just days before the settlement’s destruction at the hands of the Mount Pelée volcano. “This synopsis is a pre-text for visiting the city and discovering the daily economic, political and religious life of this legendary city,” said Tramis. The game’s exploration of French-Caribbean culture won Tramis a silver medal from the Parisian department of culture – making it one of the first games to receive official recognition for its artistic merit.

Tramis and Chamoiseau probed the history of slavery further in 1988’s

Freedom: Rebels in the Darkness

. Set once again in the French Caribbean, the game casts the player as a black slave on a sugar cane plantation who must lead an uprising against the plantation’s owner.

Freedom

mixed action, strategy and role-playing into what Tramis summed up as a “war game”.

“Fugitive slaves, my ancestors, were true warriors that I had to pay tribute to as a descendant of slaves,” she said. “At the time I made the game, these stories were not known because they were hidden. Today the official recognition of slavery as a crime against humanity has changed the world, people are aware now. I could talk through the game at a time when the subject was still painful. It was my duty to remember. A journalist wrote that this game was as important as

Little Big Man

has been in film for the culture of American Indians. I was flattered.”

Tramis and Froggy’s attempts to elevate video games beyond the simple thrills of the arcades formed part of a wider s

earch during the 1980s amongst French game developers for a style of their own. Unlike their counterparts in the UK, France’s game industry had been slow to develop. In the UK the instant success of Clive Sinclair’s computers had acted as a catalyst for the thousands of games spewed out by bedroom programmers, but France lacked a clear market leader. Only in 1983 did systems such as the British-made Oric-1 and French Thomson TO7 finally start to emerge asad omputers of choice.

[3]

Until then the French had flirted with a bewildering range of contenders from the ZX81 and Apple II to home-grown systems such as the Exelvision EXL100 and Hector. But once the Oric-1, TO7 and, later and most successfully, the Amstrad CPC, gained a sizeable following, game publishers started to form with Loriciels, Ere Informatique and Infogrames leading the way in 1983. Within months of their formation, however, the country’s video game pioneers started asking themselves what defined a French game and how they could set themselves apart from the creations of American and British programmers. A summer 1984 article in

Tilt

reported how French game designers, having cut their teeth on simple arcade games, now wanted to create something more personal, more rooted in reality, more French. Inevitably, opinion was divided about what this meant in practice, but many homed in on strong narratives, real-life settings and visuals inspired by the art of France’s vibrant comic book industry. Text adventures provided the natural home for such content. “Back then the adventure game was king,” said Tramis. “There were many more scenarios with literary rich universes and characters. There was a ferment of ideas and lots of originality. France loves stories.”

The focus on real-world scenarios reflected France’s relative disinterest in fantasy compared to the British or Americans. “I have always wanted to base my titles on a historical, geographical or scientific reality,” said Bertrand Brocard, the founder of game publisher Cobra Soft and author of 1985’s

Meurtre à Grande Vitesse

, a popular murder mystery adventure game set on a high-speed French TGV train. “The TGV was still a novelty then as it had been running for less than two years and it was something ultra-modern. At the time the driver would announce to the passengers: ‘We have just reached 260 kilometers per hour’. Nowadays it goes at 300 kilometres per hour with no announcement. The player had two hours of travel between Lyon and Paris to solve the mystery and arrest the culprit, who could not escape from the train during the journey.”

Other Cobra Soft games reflected current affairs. Among them were

Dossier G.: L’Affaire du Rainbow-Warrior

, a game inspired by French intelligence service’s sinking of Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior ship in 1985, and

Cessna Over Moscow

, a 1987 game inspired by Mathias Rust – the West German pilot who flew a light aircraft into the Soviet Union and landed in Red Square to the USSR’s embarrassment that same year. For Brocard, however, the French style was more a reflection of the personal interests and tastes of the small group of companies and individuals who were making games rather a reflection of France itself. “Game production in France was not very extensive,” he said. “When video games started in France, production involved such a small number of people that chance, I think, led things in certain directions. To my mind this issue of the ‘French touch’ is associated with Ere Informatique and the charisma of Philippe Ulrich. He is an artist through and through. He had managed to ‘formalize’ this difference.”

Ulrich was the co-founder of Ere Informatique and, like Le Breton, he was a musician before he was a game designer. “In 1978 I published my first music album with CBS,

Ulrich threw himself into learning all he could about his new computer, digesting 500-page guides to the inner workings of machine code on the ZX80’s Z80 microprocessor. His first machine code game was a version of the board game Reversi, which he swapped the rights to in exchange for a 8Kb memory expansion pack for his ZX80. Soon after he met Emmanuel Viau, another aspiring game designer, and the pair decided to form their own publishing house: Ere Informatique. Like others on the French games scene, Ulrich wanted to give his work a distinctive style but, unlike his peers, he had one eye firmly on the larger UK market. “In France, authors would create games related to their culture, while the bulk of our market was the United Kingdom, so I came up with a vague concept of world culture,” he said. Ulrich wanted Ere Informatique’s games to have international appeal – something of a no-no amongst France’s cultural elitists – while retaining a French flavour: “Our games didn’t have the excellent game play of original English-language games but graphically their aesthetics were superior, which spawned the term French Touch – later reused by musicians such as Daft Punk and Air.”