Restitution (24 page)

But there was something else that Karl knew about the situation in Prague. He was aware that the political system that had ruled so decisively for the last thirty years might actually be in decline. In recent years, the Soviet Union, long considered the primary enemy and rival of the West, was being regarded as less and less of a threat. The Soviet economy was floundering, and with it, its hold on its surrounding Communist-dominated countries. Shortly before Karl had left on this trip, there had been an article in the Toronto newspapers stating that Canada was calling for the release of Václav Havel, the renowned Czech playwright and dissident, who many were touting as the possible next president of a new democratic Czechoslovakia. Havel had been imprisoned for the last nine months for his part in demonstrations in Prague protesting the ongoing Soviet occupation. More and more protests of this kind were occurring on city streets across the country. And while the Soviets had quickly clamped down on these demonstrations, there was a sense that it was only a matter of time before the Communists would be forced to back down, or withdraw, and Czechoslovakia might once again claim its freedom from oppression.

It was against this backdrop of political entrenchment coupled with potential transformation that Karl arrived in Prague and proceeded to the InterContinental Hotel. He was surprised and impressed that the hotel had maintained its rather luxurious state. The first order of business after checking in was to call Jan Pekárek.

“It's good to hear from you,” Pekárek said. “We must meet.” There were few details exchanged over the telephone. Pekárek's voice was guarded and cautious. Karl could sense his anxiety and felt it as well. Both of them knew that someone could be listening in. “Please come to my place,” continued Pekárek. “We will talk.”

Karl took down the details, hung up the receiver, and headed outside to catch a cab. The warmth of the springtime air soaked through his light jacket and he squinted at the morning sun. He could hear the sound of the Vltava River flowing rapidly beneath the Charles Bridge, its waves lapping up against the break-wall. The scent of magnolia blossoms wafted through the air. Karl breathed in deeply and climbed into a cab. Despite the pleasant spring morning, he realized that he still bore the emotional scars of having fled this city for his life years earlier. Each corner was a reminder of those days in 1939: that street where Nazi soldiers patrolled; that bridge where Hitler had surveyed his troops; that park, once forbidden to Jews; that building that had flown the swastika. His breath quickened as his cab wove its way through the labyrinth of winding cobblestone streets, many too narrow for two cars to pass, before finally coming to a stop in front of a modest four-story apartment building.

He disembarked, glancing up. Jan Pekárek lived on the top floor and there was no elevator. After climbing the dark staircase, he reached the fourth floor and rang the doorbell. Pekárek opened the door and greeted Karl warmly.

“Please come in,” Pekárek said. “It's good to meet you.” He stepped aside, and Karl entered a shabby but tidy apartment. He faced Pekárek and sized him up. The man was of medium build, rather pleasant looking, with thick, round, dark-rimmed glasses. He wore a tired old sweater and worn trousers. When he smiled, he showed his yellowed and crooked teeth, evidence of the country's lack of adequate dental care.

Karl quickly learned that Pekárek was a medical doctor â an immunologist and a scientist of considerable reputation. He had written hundreds of research papers, which had been delivered in countries around the world, though sadly not by him. “This government would rather send a loyal comrade and Communist director abroad to represent the country, not a scientist like me. Foreign travel is a political reward here. My papers are the means to provide that to others.” Pekárek chain-smoked unfiltered cigarettes as the two of them sat talking. The ashtray in front of him overflowed with cigarette butts, and the smell of stale smoke hung in the air. Pekárek had been an enthusiastic Communist at one time. “But that was a long time ago,” he continued. “I've seen how this government has suppressed individual rights and abused civil liberties.”

His political journey had been a complicated one. During the Second World War, he had actively opposed the German fascists and had become an ardent Communist, even going so far as to join a group of partisan soldiers whose goal was to smuggle supplies to a group of saboteurs who were operating in the forests around RakovnÃk. He continued to be a vocal and passionate Communist after the war, supporting the country's overthrow of President BeneÅ¡ in 1948. Years later, he began to recognize the decline of cultural, social, and educational resources under Communist rule. And as he witnessed firsthand the restrictions on freedoms, he became disillusioned with his country's political system and was now an outspoken critic.

“Mr. Pekárek, by speaking out, are you not afraid of arrest, or, at the very least, of losing your position at your research institute?” Karl asked. Pekárek was employed at one of the state-run laboratories in Prague. How did he have the courage to oppose the system so overtly and vocally, and particularly as he had a wife and young daughter? In this regime, even those who were related to, or associated with, dissidents could be blacklisted. The risk to his family was enormous.

Pekárek shrugged, and then answered matter-of-factly, “It seems that my position as a preeminent scientist has had some advantages. I'm quite simply irreplaceable. But please,” he continued. “I insist that you call me Jan. There is too much history between our families for such formalities.” It was a perfect opportunity to move the conversation to a discussion of the events of the war. “How did your family ever manage to get out of Czechoslovakia?” Jan asked. “I understand that it wasn't possible for most Jewish people to leave once the war had started.”

“You're right. It was virtually impossible,” Karl replied. “We left days before the official start of the war, and only because my father had connections out of the country, and my mother managed to pull together the necessary papers within the country.” He quickly filled Jan in on the details of their flight to freedom. “We were lucky,” he added. “Most of our friends and family members never made it out. They perished in Hitler's gas chambers.”

The two men sat in silence. Karl wondered how much Jan really knew of the events of the war and the suffering of Jewish citizens in Czechoslovakia and elsewhere. He was Hana's age, and would have been a young teenager then, living in a rural town, raised in a milieu of latent anti-Semitism and then overt persecution of Jews. Those events would have been the norm for Jan. Furthermore, after the war, he had lived within the confines of Communism, and his life had been impacted more by those circumstances than by the events of the Holocaust. Besides, even today, most Jews living in Czechoslovakia still kept their Jewish identify a secret.

“Tell me how your sister is?” Jan broke into Karl's thoughts.

“She's well, thank you. She's married and has three children and several grandchildren. She and her husband live in Toronto, not far from my wife and myself.”

“And your mother â I was sorry to hear of her passing. I didn't know her, but I can tell from the documentation regarding the paintings that she must have been a strong woman.”

Here was the opening that Karl was waiting for, a chance to talk about the paintings. “Yes, my mother was indeed passionate,” he said as he leaned forward. “You mentioned in your letter that you had found some documentation. My mother spoke very little about this after she returned to Toronto in 1948, except to say that she had not been able to recover the paintings.” He knew he was skirting some of the facts. After all, in Karl's mind it was due to the greed of this man's grandfather that Marie had failed to reclaim her property. But Jan had expressed his willingness to return the paintings, and Karl was being careful not to offend him.

Jan stood and walked over to a large wooden desk in the corner of his apartment. He rummaged through a stack of file folders, retrieved some papers, and returned to sit next to Karl. “These are the letters I found amongst my grandfather's belongings after he and my father had died.”

Karl took the papers and quickly read through them. There they were: the letter affirming that the four paintings belonged to Victor and Marie, along with letters from Marie to Alois Jirák's attorney demanding the return of the artwork, and Jirák's refusal to do so. It was all there in front of him, the evidence of the unpleasant exchange that must have taken place between the two parties. He looked up at Jan, unable to speak.

“Take them and get some copies made,” Jan said. “I would like the originals back.” He seemed unperturbed by the documentation that implicated his grandfather in this way. “It was so helpful to see this material in writing. That's what led me to your family after my grandfather died.”

Karl nodded, folded the papers, and put them inside his jacket. “I gather from your letters that it will be difficult if not impossible to get the paintings out of the country.” Karl was still fighting to calm his beating heart. He felt the need to steer the conversation away from their family feud, and to discuss the current status of the paintings.

“Yes, I've made inquiries, and the regulations are impossible to say the least.” Jan proceeded to outline the conditions that he had previously listed in his letter to Karl.

Karl hung his head. “My mother dreamed of bringing the paintings to Canada. I just can't accept that there isn't a way to fulfill her wish.” Once again, it felt as if he had come to a dead end as far as his family's treasures were concerned.

“Would you like to see them?” Jan asked. Karl looked up puzzled. “The paintings,” Jan repeated, “would you like to see them?”

“Of course I would,” Karl replied. He had not even dared to ask this question. Surely by now the paintings were in the hands of the authorities who had come to collect them following Jan's inquiries. But perhaps Jan still had access to them. “Can you arrange for me to look at them?” asked Karl. “Where are they?”

Jan smiled. “Come with me,” he said. “I'll show them to you.“

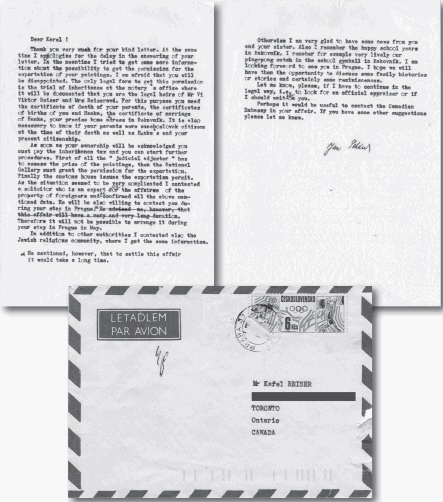

The second letter that Jan Pckárck wrote to Karl outlining the procedures he would need to follow in order to export the paintings from Prague.

Prague, May 22, 1989

JAN ROSE FROM THE COUCH and motioned for Karl to follow him. Karl stood and reached for his jacket, wondering where they were going. But to his surprise, Jan turned and headed down the hallway to a bedroom at the back of the apartment. Startled and puzzled, Karl followed behind. The small back room was sparsely furnished with one large four-poster bed piled high with a feather comforter and quilted bedcover. A small chest of drawers sat in one corner, and a rectangular wool rug lay over the worn hardwood floor. Jan went first to the window and quickly drew the curtains. Soft light penetrated through the thin blinds. The room became dimly lit, though not dark. Glancing back at Karl, Jan moved over to the bed and began to strip back the bedcovers, comforter, and several blankets. Finally, he pulled away a large sheet and there lay the paintings, neatly stacked one on top of the other and separated by more blankets and sheets. Each one was carefully wrapped in paper and tied with string. Jan unwrapped the top painting and stood back.

“I made those inquiries to the Czech authorities anonymously,” he said, turning to smile at Karl. “No one knows about the paintings.”

Karl was dumbfounded. Not in his wildest imagination had he thought that the paintings might actually be here in Jan's home, and buried in a bed! He stumbled toward the bed and ran his hand lovingly over the top painting. It was the Geoffroy â the children in the bathhouse â the one that may well have been his mother's favorite. It was in perfect condition, preserved here in this bed cocoon as if it had been hanging in a gallery. It appeared that all of the paintings were still on their stretchers, though the gold frames were gone. Karl did not know what had become of them and it didn't really matter. What mattered was that the paintings were here, all four of them, all together and safe.

“Please help me to stand them up,” Karl asked hoarsely. He still felt light-headed. Together, he and Jan unwrapped the remaining paintings, lifted them, and propped them up, each one placed against one of the four walls of the small room, nearly dwarfing the two men who stood in front of them. Even in the dim light, Karl could make out the exquisite details of each painting. The young children in the Geoffroy looked playfully and innocently at their teachers. The forest flames from the Swoboda filled the canvas with their radiance. The Spanish dancer's face in the Paoletti stared back at Karl with expectation and longing. And the housewife in the Vogel looked demure and thoughtful. Though as a youngster Karl had barely paid attention to these works of art, they now felt as familiar to him as members of his own family.