Restitution (21 page)

When Karl heard that his mother was abandoning the lawsuit, he was somewhat relieved. “At least this means that she will get out of there before the political situation worsens,” he reasoned. Marie must have anticipated that a Communist takeover was imminent. Knowing that she would have to leave or be caught in this new oppressive net, Karl assumed that his mother had come to the conclusion that there would be no point in proceeding further with the lawsuit.

“But the paintings,” questioned Phyllis. “After all she's tried to do to get them back, why would she stop now?”

It was a good question, and Karl had no answer. “She still maintains that all four paintings belong to her and to our family,” he said. “Knowing my mother, she may even be thinking that once this new political unrest has passed, she'll go back to Czechoslovakia and pick up the fight where she left off. I'm sure this isn't the end of the road.”

In February 1948, the Communist party under Klement Gottwald assumed full control over the government of Czechoslovakia. The country became a satellite state of the Soviet Union. This event would become significant beyond the impact on Czechoslovakia alone, as it paved the way for the drawing of the Iron Curtain, and the full-fledged Cold War between the East and West for the next four decades.

Karl's heart nearly came to a standstill when he picked up the newspaper in Toronto in late February and read the headlines. “Lesson for appeasers seen as Bolshevists grab Czechoslovakia.” The article that followed read:

So democratic little Czechoslovakia has gone the way of all countries upon which bolshevism has managed to obtain a firm grip.

Czechoslovakia's absorption is one of Moscow's greatest successes. As the

London News Chronicle

pointed out a few hours before the coup was achieved, if the Communists gained complete control in Czechoslovakia it would be their most important victory in Europe, because out of all their conquests the Czechs would be the first with an instinctive belief in western democratic freedom. Well, bolshevism reigns in freedom-loving Prague â at least for the time being.

9

Marie knew that she would have to get out of Czechoslovakia quickly. The borders were about to close. The memories of fleeing Prague once before rushed back into her consciousness. It was mind-boggling that her country was again forcing her to flee. She had returned believing that she and Arthur could build a stable home in the country she loved. And for a short while it had appeared as if that might be true. But now her heart ached, first for the homeland she was losing for the second time, but perhaps even more so for the loss of her precious paintings. They would remain behind, sealed within the same borders that were forcing her out for a second time. Marie, Arthur, and Hana quickly packed a few suitcases and boarded a plane for Toronto. Paul Traub, the man Hana intended to marry, was not allowed to leave with her. He was refused an exit visa by the new Minister of the Interior on the basis that, as a physician, he was needed by the country. In response, he claimed that his arm, which he had broken while skiing with Hana, made it impossible for him to practice any longer. Eventually, after paying a substantial bribe, Paul managed to get the necessary exit visa. He left the country quickly, taking no belongings, and was met in New York by a relieved Hana.

Karl was thankful to have his family back on Canadian soil. Upon his mother's arrival in Toronto, Karl questioned her about the paintings and the lawsuit. Marie's response was clear and firm. “You can forget about them,” she said. She and Karl never spoke of the paintings again.

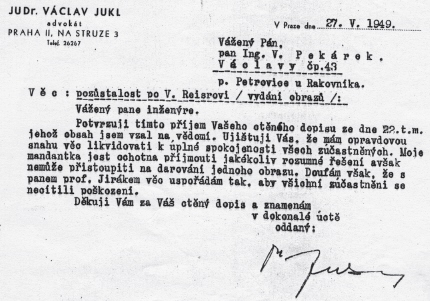

A letter from Marie's lawyer advising that she has agreed to withdraw legal action for the return of the paintings, while not relinquishing her claim to them.

Written by Václav Juki, Mario's attorney in Czechoslovakia, this letter states that Marie is prepared to accept any reasonable solution to the matter of the four paintings, except relinquishing one of them.

A statement from Alois Jirák to his laywer, which lists three of the paintings and describes that the fourth one was promised to his son-in-law, Václav Pekárek, “who risked his life and property to safeguard the paintings from occupation forces.”

PART III

A CHANCE AT RESTITUTION

Toronto, March 15, 1989

THE MAIL HAD ARRIVED earlier than usual that day. Karl paused on his way to the kitchen, newspaper in hand, glancing down at what appeared to be bills, the usual useless fliers, and a bank statement or two. There was an advertisement for a membership to a tennis club that looked interesting. Now sixty-eight, Karl had maintained a youthful vigor. While he had long ago given up skiing and cycling, he walked and hiked regularly, and was still an avid and skilled tennis player.

As he flipped through the remaining envelopes, one caught his eye. It looked like an invitation of some kind, but the return address and postage were Czech.

Who would invite me to Czechoslovakia

, he wondered.

And what kind of event would be taking place there at this time?

In the early spring of 1989, Czechoslovakia was still an oppressive place under a Soviet regime that ruled with tight, unyielding laws. State Security, the infamous secret police, was everywhere, watching its citizens and arresting dissidents. It was common practice for them to wiretap telephones, watch apartments, open and read mail, and search homes without warning. Individuals were frequently arrested for what became known as “subversion of the republic.” Citizens, at all levels of society, were “encouraged” to watch their neighbors and report any suspicious activity, or risk falling under suspicion themselves. Informers were strategically placed within businesses, schools, and community groups. The people of Czechoslovakia lived in constant fear.

There had been a brief period of liberalization, known as the Prague Spring, which began in January 1968 under the leadership of Alexander Dubèek. Under his rule the country saw a loosening of regulations inhibiting free speech, travel, and the press. Many Czechs rallied behind these progressive changes, and called for even more rapid advancement toward democracy. But this alarmed the Soviet Union, and, fearing that these reforms would lead to a weakening of the Communist Bloc during the Cold War, the Warsaw Pact nations, including the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria, invaded Czechoslovakia on August 21, 1968. Approximately ninety civilians were shot and killed, and close to 3,500 fled the country, many finding refuge in Canada which, in contrast to its policies during the Second World War, this time opened its doors to escaping Czechs. Gustáv Husák replaced Dubèek as president of Czechoslovakia and reversed almost all of his reforms. The party was purged of its liberal members, and intellectual elites were dismissed from public office and professional jobs. Control was gradually restored, and hard-line Communists were reinstated as leaders. Twenty years after the Prague Spring, Czechoslovakia was still a repressed country. With its closed borders and restricted opportunities, there were few if any celebratory events or occasions that might have prompted someone to send an invitation to Karl.

He turned the envelope over in his hands and then carefully broke the seal, removing a stiff cardboard note with formal black lettering. Its contents startled Karl. The card requested his presence at the fiftieth anniversary reunion of his former high school in RakovnÃk. And, as he stared soberly at the invitation, memories stirred.

March 15, 1989 â it was fifty years to the day that Germany had invaded Czechoslovakia, setting off the string of events that would plunge the country and eventually the world into the chasm of war. And it was fifty years to the day that Karl and his family had fled RakovnÃk to the temporary safety of Prague, and, ultimately, Canada. Karl had only visited his former homeland once in the years since his family had been forced to flee. But the truth was, he had never had any desire to return. Any sentimental attachment to Czechoslovakia that he might have retained in the early days of adjusting to life in Toronto was gone. It was as if that part of his life had ended and a new chapter â one that represented freedom and security â had been born to take its place. Despite the slight remnant of an accent that still identified him as European, Karl felt and

was

more Canadian than Czech. His entire adult life had been formed in Canada. He had found a home and a career here, had married, and had raised two children with Phyllis. Linda taught marketing in the business schools of two universities. Ted had his own successful business distributing restaurant equipment. Both had married and had had children of their own, a source of additional pride and joy for Karl and Phyllis.

Karl stared again at the invitation, wondering how the organizers had even tracked him down after all these years. Then he shook his head and smiled wryly as another thought flashed through his mind. He had not even graduated from his high school! That place was one more reminder of the virulent anti-Semitism that had plagued his country even before the war. Karl tossed the invitation aside, marveling at how the letter had instantly propelled him back to a place and time he had worked hard to forget. Memories had that power, he realized. The slightest event or object could catch you off guard and hold your mind hostage to the past.

He took another deep breath, wondering where Phyllis was. He needed a cup of tea, and wanted to talk to her about the invitation. The dog whined softly at the door, anxious to go for a walk. “Later, Quinta,” Karl said firmly. At Karl's command, the brown Welsh terrier sniffed and reluctantly turned away.

Karl was just about to head for the kitchen when one more envelope caught his eye. This one had been at the bottom of the pile and might have been overlooked completely had it not been for its familiar onionskin wrapping. It was an airmail envelope, Karl realized, and also from Czechoslovakia. Two letters from his former homeland in one day! It was more than he had received in years. But it was the salutation on this envelope that made Karl catch his breath.

Mrs. Marie Reiserová

*

or anybody from the family.

More memories! Marie had died five years earlier. Her heart had begun to fail her in her advancing years. One mild heart attack followed another, and gradually she began to fade. This was followed by a series of ministrokes until, in her ninety-first year, Marie ended up hospitalized for what would prove to be the last time. Karl visited her every day, sitting by his mother's bedside and often helping to feed her. Her declining health and the countless physical examinations by the doctors at the hospital frustrated her terribly. Karl talked about his children and grandchildren, and these conversations always put a smile on Marie's face. Though she now had difficulty speaking, her mind was as sharp and clear as ever. It was here in the hospital that she also reminisced about Czechoslovakia.

“You know, in spite of losing so much, I can honestly say that my life has been happy,” she said one afternoon, propped up in her hospital bed. Karl was astounded that, in spite of her frailty, she maintained this strong and positive attitude. “There were only a few things I missed of what we had to leave behind,” she continued. “Our possessions were only objects, nothing compared to the fact that all four of us were able to get out alive. But, I've always been sorry I had nothing to leave you and Hana. There should have been a family legacy.” She paused and turned her head to stare out the window while Karl looked on. It was the closest she had come to talking about the four paintings and her ill-fated attempt to retrieve them since returning from Prague in 1948.