Resurrection Man (4 page)

Father would be proud.

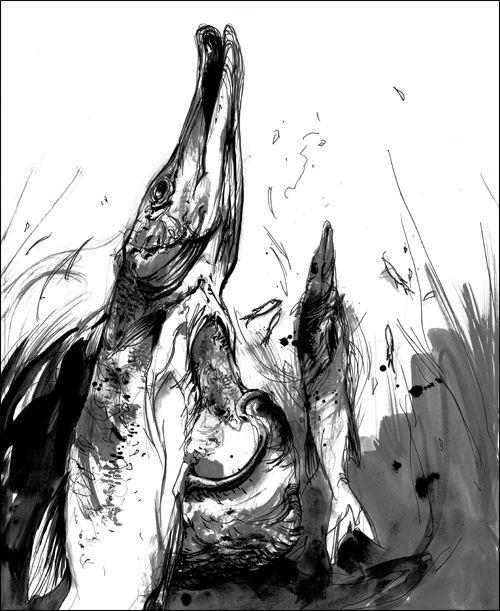

Flipping the fish over, Dante cut off the fins and slit its belly open. The viscera slid out in a pool of blood. Carefully Dante dissected the bladder, liver, heart.

Inside the stomach, a clutch of shapeless half-digested minnows, the remnants of two small perch, and a curiosity: another pike, a little one half the length of his hand, and so fresh he could have cleaned and served it too. It couldn't have been swallowed more than an hour before Dante had avenged its murder.

Delicately Dante took out the smaller fish, and began a second autopsy.

In its belly he found a square golden ring. It could have been a man's thick wedding band, though Dante could not remember having seen a square ring before. With the tip of his knife he pulled it clear of the viscera and studied it in the broadening daylight.

Aunt Sophie was in the kitchen, brewing a cup of willow-bark tea, when Dante returned to the house. When he showed her the ring she screamed and fainted. Later, when Mother brought her around, Aunt Sophie swore and coughed and lit a cigarette with shaking fingers, but she would not speak to Dante, or look at the strange square ring.

* * *

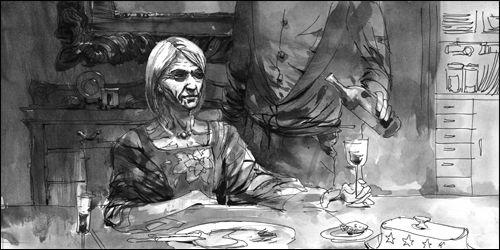

At dinner they pretended nothing had happened. The silences were excruciating. For Dante it was like being a child again, fidgeting while grown-up secrets filled the air.

At first it looked like Sophie wouldn't be able to cook, after the shock Dante had unwittingly given her, but after a short rest upstairs—they could hear the clink and clatter of her coins—she decided to return to the kitchen, and prowled it, scowling, for the rest of the afternoon, vengefully slicing vegetables and hammering her meat into mute submission.

Beef broth came first, salty and black as blood. Countless afternoons Dante had helped her make it, chopping vegetables and fussing with seasoning, until at four o'clock she would scoop up the bones in her big wooden ladle and fish out the marrow for them to spread on toast and eat. For a proper broth all the vegetables came out just before serving, making two tureens: one black bouillon with noodles in it, the other beef-stained potatoes and onions and carrots, and peppers slathered with so much horseradish that eating them was like having your sinuses dosed with ammonia.

Jet scooped potatoes onto his plate. "So they shot a minotaur in Westwood Heights yesterday."

"Westwood Heights!" The little worry lines in Mother's white forehead deepened and she couldn't help glancing at Dante. "I thought those things only haunted The Scrubs, or maybe Peter Street."

"Extra, Extra: Minotaurs manifest outside the slums." Jet shrugged. "The magic's rising all the time. Who knows what brought it on—fear of Volvos? I don't know. I shot some pictures for the paper."

"Maybe the Mammon Men have oracled a stock crash coming," Sarah suggested. "How many people did it get?"

Jet helped himself to some peppers and horseradish. "One family and a paperboy, plus two more injured. It was a slasher: standard dark figure with a knife. When they shot it, it was wearing the face of its last victim."

Dante shuddered, not sure whether Jet meant the minotaur had flayed one of the people it had killed and made a mask of the skin, or whether, governed by the strange dream-logic that drove such manifestations, the monster always appeared as its victim's twin. Both possibilities seemed equally horrible.

"But still. You would never have seen that five years ago." Mother's small head shook in crisp disapproval. Dante noticed that her gorgeous hair, once red as fire, was now embering into ashes. Guiltily he wondered when that had happened, and why he hadn't noticed until now.

"Oh, it's clearly getting worse, there's no doubt about that," Father said, filling Mother's wineglass with a nice French white from the mid-eighties. "I remember when we first started hearing of this sort of thing—at the end of the War, when they liberated the concentration camps."

"The Golem of Treblinka," Jet said.

Father filled his glass. "There was one at Dachau too: killed two hundred prisoners and four guards, and they never shot it down." He moved around the table, pouring for Sarah and Aunt Sophie. "Now, what's needed is a scientist with some aptitude for this angel business to make a thorough study of the phenomenon." He paused, standing over Dante's shoulder. "There are tremendous contributions to be made. The man who learns enough to banish these manifestations, or better still stop their formation, will be the Pasteur or the Fleming of his time." He emptied the bottle deliberately into Dante's glass.

"Hurrah for that unknown savior," Dante said.

Mother looked at Dante sharply, her hand hovering over a dish of honey-ginger carrots. "Don't you go looking for trouble."

Father returned to his place at the head of the table. " 'But the bravest surely are those who have the clearest vision of what is before them, glory and danger alike, and yet notwithstanding go out to meet it'—Thucydides."

"And after all, what are his alternatives?" Jet mused, ignoring Dante's glare. "He certainly doesn't

apply

himself to anything else— Was it not Hippocrates who said, 'Idleness and lack of occupation tend—nay, are dragged!—towards evil!' "

Dr. Ratkay scowled.

Sarah ladled black broth into her bowl. "Parody is the sincerest form of flattery," she observed, smirking at her father.

Aunt Sophie snorted over her wine, her smoke-blue eyes angry, her old hand trembling around the stem of her glass. "Dante get hurt playing Angel? Pfeh! Dante couldn't make a living reading tea leaves."

A honey-ginger genie steamed up over the table as Mother took the lid off the carrots. "That's like saying he's not a good enough shot to blow his own head off," she said tartly.

"Thanks for the vote of confidence, Mom."

"Point and set to Mother," said Sarah, who kept score of such things.

After soup and vegetables came a tray of roasted peppers stuffed with spiced beef and rice. In the middle of the table, proud as the head of John the Baptist on its silver platter, a mountain of wienerschnitzel loomed: veal on one side and pork chops on the other, breaded and fried in lard, golden-brown and glistening.

"The American Medical Association estimates that each schnitzel takes five minutes off your life," Sarah remarked, helping herself to two of the veal.

"Not if you don't inhale," Jet countered. "And don't believe everything you read about the dangers of secondhand schnitzel either."

"More self-serving lies from the lackeys of the schnitzel industry," Sarah retorted, shaking her head. She looked appealingly to Father at the head of the table. "Tell him, Doctor!"

A piece of veal impaled on his fork, Dr. Ratkay paused. "Tragic," he said solemnly. "The arteries harden, the belt line disappears. The human waste of it!"

They groaned as he patted his waist, where a small pot belly distended his shirt-front.

"I could quit any time I wanted," Dante said, mouth half full. "Look—I'm under a lot of stress at the lab. A couple of schnitzels calm me down. Is that so wrong?"

Jet cut his schnitzel from the bone, cut the fat from the schnitzel, dissected out a precise, bite-sized morsel and placed it in his mouth. "Oh, hey," he said. "Menthol."

"Pfeh! When I was young, every day we eat for breakfast a slab of bacon fat between two slices of lard," Aunt Sophie said, in a strong Hungarian accent. She pointed proudly to her own arms, still sturdy after seventy years. "You think I get from bran flakes and skim milk so strong?"

Aunt Sophie hadn't lived in Hungary since 1929, though she visited when she could. She spoke perfect English, and swore perfect American.

She lifted a slab of schnitzel, golden and gleaming, and snorted, scoffing at her little brother and his medical degree. "To hell with you," she said.

* * *

Aunt Sophie's Hell was a very definite place. Growing up, Dante was sure that she remembered each thing she had consigned there, why she sent it and where it lay.

Aunt Sophie was odd, even for a grown-up. Two packs of Virginia Slims a day had turned her eyes the color of cigarette smoke; as a boy, Dante always felt their fire in her, smoldering. She cooked strange things, like bread fried in lard, and ate them at strange times, like five in the morning or three in the afternoon. Dante once found her at the kitchen table at two A.M., still dressed, frowning at a pattern her magic silver dollars had made while she sipped a mug of fennel-seed tea and ate tiny pickled onions, one after another. She had lived with them forever, and loved Dante dearly, but she never came to his birthday parties, not even once.

She was also the first grown-up he could remember hearing swear. He was seven at the time; her hair was still long and straight and black, her fingers thin and yellow at the tips.

The City had not crept up to the edges of their community then; the kids still went to a country school that served all grades. It was early spring, and Dante had trudged home from the bus stop half a mile through the slush, carrying a strange truth inside himself. A Grade 11 named Jason Babych had died. Something to do with a girl, Jet said. Got up before dawn and shot himself behind the family barn. His dad had found him there.

How Jet knew these things Dante never understood, or even questioned. Jet was awake in a way other kids were not. He understood the grown-ups' codes and ciphers; he read the secrets behind their looks and hesitations as Dr. Ratkay read Parkinson's in the tremor of an old man's hand, or heard the rot in people's lungs when they coughed.

What Jet found out he told Dante, forcing him to share the unclean knowledge. One of Dante's clearest childhood memories was the feel of the secrets Jet thrust on him: sinister things, heavy with obscure adult meanings.

The Grade 11 dead, slumped against his father's barn. Something to do with a girl.

Knowing about it made Dante feel dirty. He wanted to talk to someone, someone who wasn't Jet.

Mother would be angry that he knew. She worked at the school. She probably knew Jason Babych, Dante realized.

They would have called Father. He might already have cut into Jason's dead body with one of his scalpels, only it wouldn't hurt, because Jason was dead.

So Dante found Aunt Sophie and moped, and let her make him a piece of toast, and told her, and waited for her to do a magic trick or tell a funny story that would make him feel better.

She didn't. "Bloody fool," she said angrily. "Hah! ...I bet Jet told you that, didn't he?"

Dante didn't answer.

"Of course he did. Little spy." Angrily she filled the kettle for tea and banged into the stove. She was still strong then, very strong. "I'll tell you what, that boy was a fool, a coward and a fool. To kill yourself—that's the one most contemptible thing you can do. Remember that! It's stupid and it's disrespectful. He's a coward that does that. Can't stomach the hard going, that's all it is.... A coward and a traitor, that's what he was, the bastard," she finished, so fiercely Dante started to cry.

She wasn't seeing him, though; Aunt Sophie was staring at something far in the distance, or the past. "To hell with him," she said at last. "To hell with him."

T

HINGS THAT ARE HOLY ARE REVEALED ONLY TO MEN WHO ARE HOLY.

&8212;H

IPPOCRATES