Return to Skull Island (12 page)

Read Return to Skull Island Online

Authors: Ron Miller,Darrell Funk

“How do you know all this?”

“Good heavens, Carl, you need to get around more.”

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

While I could have cut the tension on board the

Venture

with a butter knife, things went along more smoothly than I would have expected during the following week. Everyone knew their job and did it—though Englehorn’s crew made no effort to hide their contempt for the Japs. Still, no one caused any serious trouble, no doubt because of the cash reward they knew was waiting at the end of the trip. The crew might have been patriotic but they were also practical.

We were steaming through the Strait of Malacca, with the Indian Ocean not far ahead. That’s all I was willing to tell Ito: that the island was somewhere west of Sumatra, figuring there was no good reason to give him the exact location until he needed it and every reason not to. There was no need for intimidation or threats. Ito knew he’d get the information eventually. It might have frustrated him, but if it kept him awake at nights he didn’t show it and I didn’t care.

The weather was fine, the waters of the Strait were smooth and we were making something like eight or ten knots. We were in the narrowest part of the Strait. A mile or so to the south was the almost uninhabited, swampy coast of Sumatra. About thirty miles north was the small town of Port Dickson. Obeying Ito’s orders, Englehorn had been carefully avoiding contact with any inhabited areas since leaving Japan. He wanted no one asking questions regarding our destination.

Buck, Andrews, Pat and I passed the time playing poker or swapping stories. The two adventurers seemed to get along with Ito and his men. But they’d had a lot of experience dealing with foreigners, especially Orientals, and approached the whole affair pragmatically. We feigned a spirit of camaraderie and good sportsmanship and invited Ito to join us. As we’d figured, he was no match for four hard-boiled American cardsharps (Pat showed us some stunts that would have put Dai Vernon to shame) and, soon enough, begged off future invitations and left us strictly alone.

So every evening we made a point of meeting in one of our cabins where we’d split a bottle of bourbon and talk about ourselves. I’d known Frank for some time, of course, our paths having crossed many times. Neither Pat nor I had ever met Andrews before, though he and Frank were old chums. Pat was an unknown to all three of us, though Frank and Roy wasted no time in trying to remedy that. Fat lot of good it will do them, I thought smugly.

Buck talked about the practical aspects of bagging a live dinosaur and transporting it to Europe or the States.

Although Nakayama had called Buck a “big-game hunter,” the truth was that the dapper American’s reputation had been built on his success at capturing live animals for circuses and zoos. Hence his famous nickname: “Bring-’em-Back-Alive.” He talked incessantly about the exhibition of prehistoric creatures he was going to create at the coming World’s Fair in New York.

“It’s too late for the Century of Progress exposition,” he lamented. “My ‘Jungle Camp’ is already up and running. Had nearly a million see it already. But that’ll be peanuts compared to the show I’m going to put on in old New York!”

I could have told him something about importing prehistoric monsters to New York, but he’d been somewhere in the middle of the Malay Peninsula when I’d had my troubles with Kong, so it all seemed a little abstract to him. I was pretty sure he suspected me of exaggerating the danger as a kind of dare.

I did find we shared an interest in movies. I told him how much I’d admired “Bring ‘em Back Alive”, a film he’d recently released, and we spent a lot of time comparing notes.

“It’s been a big hit,” Buck said, “but I don’t know if I really want to get into pictures. At least not that kind again. Nearly lost my cameraman to a hungry python.”

I told him that I’d lost

my

cameraman to a hungry brontosaurus and he just chewed on his cigar.

Andrews was a little harder to warm up to. Not because he was a bad sort or anything like that. It was just that unlike Buck or me he was a real scientist, even if he was an outdoorsman and adventurer at heart. About ten years ago he’d run across the first fossil dinosaur eggs somewhere in Mongolia or some such place. And just a couple of years ago, on one of his last trips to China, he’d found some mastodon bones. So it’s probably needless to say that he was champing at the bit to see a living, breathing specimen of one of these monsters. He was probably the only one of us who might have some real idea on how to handle the beasts once we found them.

Pat fell back on her habit of chatting away knowledgeably on every subject imaginable. She seemed to know as much about wildlife, hunting and prehistoric animals as Buck and Andrews—which only served to impress them more. She chatted about everything, of course, except herself.

I said that she was a cipher to the two adventurers, but in truth I wasn’t so sure about that. Just as with Nakayama and a couple of others, I had the distinct feeling that both men already knew Pat or had met her somewhere before. There seemed to be some secret accord between them, though, because while they acted like complete strangers on the surface there was always a stray glance, an odd tone of voice, a weird sense of

knowingness

that passed between them once too often.

“I’ve heard tell these are pirate waters,” Andrews said. “What do you think, Frank? This is your territory.”

“The Malay pirates have been a problem for five hundred years. But between the Dutch and the British East India Company, most of the pirates have been eradicated. Piracy in the Strait has hardly been an issue since the turn of the century.”

“Roy is right,” Pat said. “The Strait is one of the major shipping lanes of the world. It’s well patrolled by the navies and coast guards of the surrounding countries. The pirates are simply outmanned and outgunned.”

A heavy fog rolled in overnight. Englehorn reduced our speed and gave orders to start the fog horn. As Pat had pointed out, the Strait is a busy shipping lane and there was a real danger of collision.

Regardless of the weather, Ito’s crew went through their drills on the aft deck every morning. And every morning, like clockwork, Pat did her weird exercises, much to the consternation of the Japs and much to our amusement. The fog lent a weird quality to both of these activities that morning. There was nothing visible ten yards beyond the ship’s railings. There was barely a sound from the calm water and the fog absorbed what remained, other than the mournful hooting the fog horn. All sounds seem to echo back from the fog, giving a sense of enclosure, as though the Japs and Pat were working out in a gymnasium.

I was watching Pat work out, since she is far more interesting than fifty-five Jap marines, when the lookout in the crow’s nest shouted, “Vessel off the starboard bow!”

I could hear the telegraph jingle in the wheelhouse behind me and the sound of the engines immediately slack off. Englehorn stepped out and shouted, “What is it?”

“Boat, sir! Coming up to the starboard bow!”

Sure, enough, there was a sizable craft slipping up out of the fog. It was a big

twaqo

, which I was more used to seeing in the waters around Singapore though they weren’t uncommon as coasters in Indochina. It had been modernized. Its sails were furled and I could hear the

putt putt

of a gasoline engine. There seemed to be about a dozen men on board. The

Venture

came to a stop as the native boat slid alongside.

“What do you boys want?” Englehorn shouted from the bridge.

“Got fruit!” returned a voice from the boat. “Got veg’table! Coconut!”

“What do you think, Captain?” I asked.

“Don’t see any harm in it. We’ll be out of the Strait in a day. Once we’re in the Indian Ocean there won’t be any chance for fresh supplies until we get to the island.”

I had to agree that they looked harmless enough. The

twago

certainly wasn’t my idea of a pirate ship nor a dozen half-naked natives my idea of pirates.

Buck, having spent some considerable time in Sumatra, knew the local lingo and offered his services as a translator. Through him, the captain gave the order to load the fruit and vegetables but to let no more than six of the natives on board.

The Sumatrans began passing baskets of produce from the deck of their

twaqo

to the men at the head of the

Venture’s

gangway. This was interesting for about five minutes, then my attention wandered elsewhere. Elsewhere being largely Pat, who had changed into white shorts and blouse and a pith helmet. She joined me on the bridge.

“Very colorful,” she said.

“I notice that Ito and his boys have gotten shy.”

“They disappeared below deck as soon as the native boat was spotted. I guess they don’t want to take any chances of someone noticing they’re here and passing the word along to someone who might make some objection.”

I turned back to the deck below me just in time to see an especially large basket overturned. Instead of a flood of melons or mangos spilling over the deck, there was an unexpected metallic clatter. Before it dawned on me what they were, the guns were in the hands of the six natives who’d been allowed on the ship. On the

twago

below, guns magically appeared, including a deck-mounted machine gun that had been hidden by the furled sail.

“Good God!” Pat said. “Pirates!”

I saw her hand instinctively go for her hip, but she was unarmed—for which I was thankful.

One of the natives on deck, evidently the leader, shouted something I didn’t quite catch. It was probably meant as an order to those of our crew who had been transferring the baskets to the galley’s storeroom. Most of them just stood and stared. The exception was our first mate, Mudhole Parker. He had been on the forecastle where he could oversee the deck. Without a moment’s hesitation, he drew his automatic and dropped the native nearest the railing. The man clutched his chest and tumbled over, falling into the water between the ship and the boat.

The leader of the Malays—and there was no doubt in my mind that these were examples of the very Malay pirates we’d recently been discussing—drew a long, curved sword and shouted what could have only been the Malay word for “attack!” or “kill them all!” Whatever it was, it galvanized his men. Two of the

Venture’s

sailors who’d been helping with the lading were shot down where they stood. Meanwhile, the machine gun opened fire. It was too low to harm anyone on deck, but it raked the bridge above it. Pat and I ducked back against the wheelhouse as paint chips and splinters of metal sprayed around us.

All other things being equal, the pirates would probably have taken the

Venture

with hardly a cup of blood being spilled, white and Malay combined. All things weren’t equal, of course. The pirates had no knowledge of the existence of Ito’s men, who now rushed the decks. If the natives had never before encountered organized, professional armed resistance this was a tough lesson for them. They never had a chance.

Ito made a clean sweep of the deck. His men were efficient, systematic, brutal and it was all over in less than a minute. They showed neither mercy nor quarter. It was methodical extermination, done as cold-bloodedly as he would have rid the ship of rats. This extended to the Malays who had remained on the

twago

. They were shot and their boat sunk by a well-placed grenade dropped into an open hatch. Meanwhile, the bodies on the deck were unceremoniously thrown overboard. In five minutes, it was as though nothing had happened.

Ten minutes later, we were taking stock of the damage. We’d lost only three men, all from the

Venture’s

crew. The Japs had suffered no losses. But there was one mystery that puzzled all of us. Frank Buck was missing. He’d been on the deck, translating orders for the Malay chief, but when the fighting was over he was nowhere to be found. The assumption was that he’d gone overboard in the first seconds of the attack, his death unnoticed in the general confusion.

That was Ito’s conclusion, at any rate.

“I’m sorry your friend was lost,” he said, looking more annoyed than remorseful. “He would have been of great value when we reach the island.”

“Yeah,” I said, “it must be pretty tough for you.”

Later, Pat took me aside and said, “I think Buck went overboard all right, but I think he did it intentionally. We’re scarcely half a mile from shore, you know.”

“You think he ran out on us?”

“No—Buck’s not that sort. That’s the mouth of the Rokan River up ahead. It’s some forty miles of swamp overland and maybe a little less by water to the nearest village, Bagan Siapiapi. I think that’s where he’s headed. If anyone could make it, he could. If he does, the authorities will know within a week all about the plans of our friend Ito.”

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

We reached the island about ten days later. When I knew we’d gotten within about fifty miles, I gave Ito the coordinates.

“Twelve degrees south, seventy-eight degrees east,” he murmured, looking over the Englehorn’s charts of the Indian Ocean. He looked up at me and scowled. “There is nothing there.”

“Don’t be sap. If it was on the charts everyone would know about it. But it’s a hundred miles from any shipping lane. No one’s been there for centuries.”

“You understand there will be consequences if there has been a hoax?”

“You worry too much. Trust me, the island’s there is all right. Where in the world did you think I found Kong in the first place? Macy’s?”

And the island

was

there, exactly where I said it would be. We both stood looking at it in silence for several long minutes. There was no way for me to tell what Ito was thinking, but I couldn’t help shuddering. The distant green shore and the mammoth, barren mountain behind it brought back too many uncanny memories. The domed shape of the mountain with its three well-placed cave openings was just a little too skull-like to suit me.

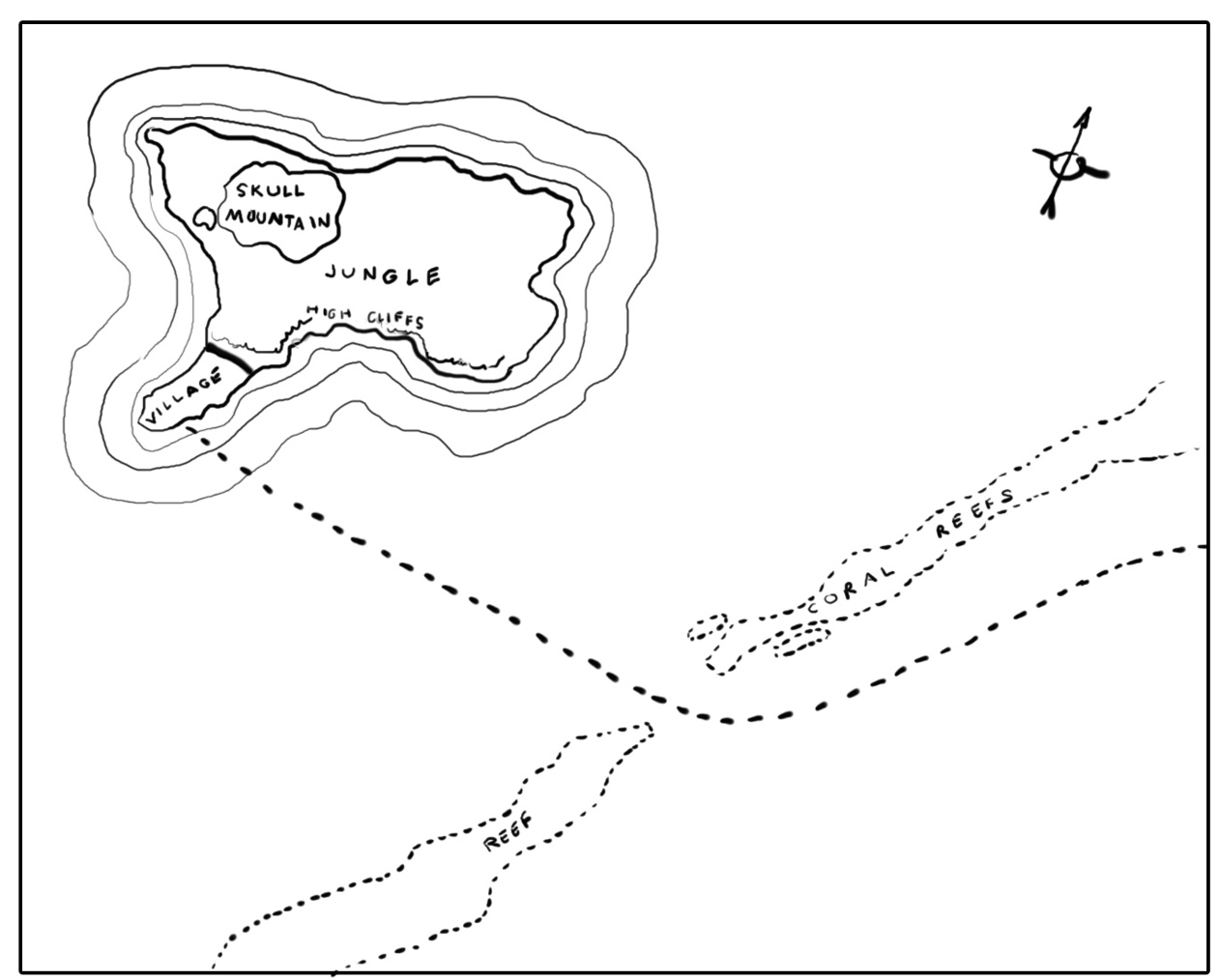

I told Ito about the reefs that surrounded the island and we approached carefully. But Englehorn knew exactly where they were. He had the anchor dropped about half a mile from where we could see the waves churning over the deadly barrier. I drew a little sketch map of the island and the reefs around it. Englehorn watched and grunted his approval when I’d finished.

I told Ito about the reefs that surrounded the island and we approached carefully. But Englehorn knew exactly where they were. He had the anchor dropped about half a mile from where we could see the waves churning over the deadly barrier. I drew a little sketch map of the island and the reefs around it. Englehorn watched and grunted his approval when I’d finished.

“There’s only one way in,” I said, pointing to my drawing. “That gap there.”

“Looks easy enough,” said Ito.

“Don’t kid yourself,” replied Englehorn. “That’s as tricky a bit of navigation as I care to do. I don’t know how we did it the first time. Sheer dumb luck, I say. Even having done it once, it’s going to take some fancy footwork to do it again.”

“That,” Ito said icily, “is what you are being paid for.”

Meanwhile, Ito locked himself in the radio shack with his radioman. I could clearly hear the clicking of the key, which chattered for nearly an hour.

“I wish I knew what they were saying,” I told Pat, who I’d found casually leaning next to the radio shack’s door.

“I do,” she said. “The transmissions are being run through their coding equipment. If I’d been picking it up by radio, I wouldn’t have a clue what it was all about. But I’ve been listening to the key, which let’s me hear the message before it’s run through the coder. It’s ordinary Morse. In Japanese, naturally, but that’s no problem, of course.”

“Of course.”

“There’s a lot of chit-chat and I can get only the outgoing half of the conversation. The incoming half is in code and only Ito is seeing the translation of that. But it’s been easy enough to follow the gist.”

“So what’s it all about?”

“Invasion, Carl! War. The Japanese have ambitions far beyond China. Everything we saw in Shanghai and Manchuria, it was all just prelude. With the resources they hope to find on the island, the Japanese plan to invade the entirety of Southeast Asia, south from China to Sumatra, west as far as India. And even worse, so far as we’re concerned at any rate, this is the end of the trip for us. Nakayama and his masters have no intention of either the

Venture

or its crew ever leaving here.”

“We’ve got get out of here and we’ve got to get word to Washington.”

“Where’s there to go? There’s no land within three thousand miles in any direction.”

“That’s not quite true,” I said.

Pat followed my gaze toward the distant island. “I get your drift,” she said.

We needed to wait until the next day, after Englehorn had threaded the pass between the reefs. The island itself shelved off quickly, with deep water less than a hundred yards from shore, allowing Englehorn to anchor close in.

We were not far from where a stubby peninsula joined the main body of the island. The native village had been on the peninsula, but I didn’t see any signs of life. Human life, I mean. The top of the mammoth stone wall was just barely visible above the treetops. I knew it cut off the peninsula, running from the west to east shores, but I could see little or nothing of its nearer terminus what with all the trees, giant ferns and whatnot. Beyond, to the north, was the looming bulk of Skull Mountain with its cavernous eyes.

The

Venture

anchored and Ito’s men immediately began preparing to unload their tank and whatever other unholy they’d stored in the hold. I had been wondering how they’d plan to get a tank onto the island but shouldn’t have been surprised when I found out. A prefabricated raft was the first thing to be assembled. Supported by enormous inflatable rubber pontoons, it could have carried half a dozen tanks.

“This is going to take them all day,” I told Pat. “There’s no moon tonight. It should be a snap to take one of the ship’s boats and make the shore. Everyone will be either too tired or too busy to notice. It’d be the last thing in the world Ito would expect.”

“I hope so. But what do you expect to accomplish once you’re there? I mean, according to you, the island is some sort of prehistoric zoo. Seems to me you’d just be making Ito’s job easier since he’d no longer have to worry about getting rid of you.”

“Yeah, but he still needs me. It was the fact that I’d mentioned seeing pools of crude oil that got the Japs all wound up in the first place.”

“That’s what I understood from what I overheard. Apparently your description of the island’s geology was pretty thorough. They’re certain there’s oil, natural gas and who knows what all minerals and ores here.”

“Well, they’ll never find them on their own, not in this decade at any rate. If Ito doesn’t want to spend the rest of his life turning over every leaf and rock on the damned island, he needs to know what I know.”

“Still, I don’t see how you plan to get word out.”

“Let’s worry about one thing at a time.”

We told Andrews about our plans and he was all for it. Probably saw another book in it for him but whatever his motives might have been, he was an experienced outdoorsman and it’d be good to have him along.

We needed to get some supplies together, and weapons, too, if possible. This proved easier than we’d thought. Ito was so busy, and so confident in our helplessness, that he paid us little attention. He was occupied enough in overseeing both his own men and Englehorn’s that he pretty much dismissed Pat, Andrews and me as being relatively harmless.

One of the first things Ito had done after taking over the ship was to commandeer the

Venture’s

gun locker. But he hadn’t checked our baggage. Turned out that Andrews had come well-heeled and I was pretty sure that Pat packed more than just the big Colt revolver she kept in her purse.

“Over the past few weeks,” she said, “I’ve been poking around in the hold and know where some of the Jap weapons are stowed. At least the stuff we could handle.”

“You think you could get hold of some of that?”

“Sure. Why not?”

I saw no reason to doubt her. I volunteered to find some food. I knew we wouldn’t need much. Skull Island has as much to eat as it has things that want to eat you, but we’d need something until we felt safe enough to forage on our own. There was plenty of fresh water on the island, too, so a couple of canteens would suffice us to start.

That evening we played poker as usual, figuring that sticking to our routine wouldn’t raise any suspicions in Ito’s crafty Oriental brain. In fact, I figured that Ito had gotten so used to our evening ritual that he had grown to completely ignore us.

We slipped out of Andrew’s cabin around two, making sure to leave the light on behind us. We had each spent the afternoon smuggling whatever we could in the way of supplies, though we knew there’d be precious little we could easily and safely take with us. We split up the supplies and stowed them in our backpacks. Pat had found what she said was a Japanese Type 38 carbine along with a couple of boxes of cartridges. She had the rifle slung over her shoulder while her rucksack rattled ominously.

The sky was moonless and slightly overcast. The darkness was complete. It looked like a velvet blanket had been draped over the ship.

One of the

Venture

’s boats had been lowered that afternoon so Ito could supervise the assembly of the raft from it. It was tied alongside the ship, and on the island side I was glad to see. We unreeled a rope ladder and let it drop over the railing. It further end landed in the boat with a soft

thump

. The sound probably hadn’t carried ten yards, but I looked around nervously. There were guards only at the bow, stern and the main hatch. Ito, for all his efficiency, had become complacent, lulled by the remoteness of the island and his self-assurance that escape would be pointless. His only worry was the possibility of sabotage, so he had his men focused on protecting his precious cargo.

We scurried down the side of the ship and in two minutes were in the boat and in another two were far enough away that the darkness cloaked us completely. Andrews and I each took an oar and pulled for the shore. We weren’t especially worried about making any noise by that point: the surf pounding over the reef and on the distant rocks and beach masked any sound we were making. Our only worry was that the missing boat or empty cabins might be discovered prematurely. We’d left the lights burning in Andrew’s cabin in the hope it’d fool any nosy Japs into thinking we were still intent on our game.

The beach shelved gently so we were able to slide well up onto shore. We hopped out into only a few inches of water. The jungle grew down to within a few yards of us and we would have liked to have pulled the boat into its shelter so it would be harder to spot from the ship. But the thing probably weighed a ton and was beyond the three of us to move. We’d just have to take our chances. The best thing would be to get as far from the boat and under cover of the jungle as quickly as possible. We gathered our packs and bags, everything we could carry, and scuttled into the gloomy forest.

If you’ll take a look at that sketch map I drew for Ito, you’ll see a peninsula sticking out toward the south-southwest. This is cut off from the main part of the island by a heavy dark line. That is the titanic stone wall the natives had built to keep Kong at bay. It had worked just fine until it had gotten between the big monkey and Ann Darrow. Then it was just too bad for the giant gate and the village it was supposed to protect.

The spot where we had landed was just to the north of where the wall met the sea. From here on up, the coast quickly turned into high, rocky cliffs that fell directly into the sea. But between where the cliffs began and the end of the wall was a gap that, I hoped, would give us access to the interior of the island.

I could see the end of the wall to our left, looming like a skyscraper above the trees, a black silhouette against the starry sky. With a gesture, I told the others to follow me and we silently slipped into the dense forest.

After we’d gotten a hundred yards in, Andrews touched my shoulder. I paused and felt him lean his face near mine.

“It’s best we get as far as we can while it’s dark,” he whispered. “If everything you’ve said about this place is true, we’ll be safest then. Most reptiles are diurnal. They don’t hunt at night. We should be all right until first light.”

I told him that sounded jake to me.

Pat had gone a few paces ahead and when I glanced up, I saw a gleam of light. It had never occurred to me to bring a flashlight and I was glad she did. And she’d waited until it would have been impossible to see the light from the ship before turning it on.

“Good idea,” I said, coming up beside her.

“We wouldn’t get ten feet further into this jungle otherwise. We were lucky to get this far without killing ourselves.”

She was right, of course. The edge of the jungle, where it came down to meet the sea, had been fairly easy going, even in the near pitch-darkness. Tides and storms had kept the forest floor fairly clear and the trees didn’t grow close together. But I could see that an entirely different story was ahead of us. Vines the size of transatlantic cables covered the ground in looped tangles. More vines hung from above, just waiting to garrote us. And the trees and giant ferns were closing together into a solid mass. Even in the beam of the powerful flashlight, I could see little ahead of us but blackness.

Fortunately, I knew there was a large clearing near the middle of the wall, on its north side. It was where the natives had built a kind of altar for their human sacrifices to Kong. It was only a mile or two from where we were. If we kept as close to the wall as we could, we only needed to follow it until we came to the clearing. We’d be pretty safe from Ito, too, at least for a while. I hadn’t indicated the clearing on the map and he had no idea it was there.

It was a slow, painful process—and nerve-racking as hell, not knowing what was in front of your face. I’d seen the giant spiders that’d eaten the men at the bottom of the ravine into which Kong had dumped them . . . and I could all too easily see running into one of their webs. With the spider on the wrong side.

For my part, I figured a known danger was better than an unknown one, and as for Pat and Andrews, they were safe in their ignorance. So we forged on ahead.