Rework (8 page)

Authors: Jason Fried,David Heinemeier Hansson

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General

Good enough is fine

A lot of people get off on solving problems with complicated solutions. Flexing your intellectual muscles can be intoxicating. Then you start looking for another big challenge that gives you that same rush, regardless of whether it’s a good idea or not.

A better idea: Find a judo solution, one that delivers maximum efficiency with minimum effort. Judo solutions are all about getting the most out of doing the least. Whenever you face an obstacle, look for a way to judo it.

Part of this is recognizing that problems are negotiable. Let’s say your challenge is to get a bird’s-eye view. One way to do it is to climb Mount Everest. That’s the ambitious solution. But then again, you could take an elevator to the top of a tall building. That’s a judo solution.

Problems can usually be solved with simple, mundane solutions. That means there’s no glamorous work. You don’t get to show off your amazing skills. You just build something that gets the job done and then move on. This approach may not earn you oohs and aahs, but it lets you get on with it.

Look at political campaign ads. A big issue pops up, and politicians have an ad about it on the air the next day. The production quality is low. They use photos instead of live footage. They have static, plain-text headlines instead of fancy animated graphics. The only audio is a voice-over done by an unseen narrator. Despite all that, the ad is still good enough. If they waited weeks to perfect it, it would come out too late. It’s a situation where timeliness is more important than polish or even quality.

When good enough gets the job done, go for it. It’s way better than wasting resources or, even worse, doing nothing because you can’t afford the complex solution. And remember, you can usually turn good enough into great later.

Quick wins

Momentum fuels motivation. It keeps you going. It drives you. Without it, you can’t go anywhere. If you aren’t motivated by what you’re working on, it won’t be very good.

The way you build momentum is by getting something done and then moving on to the next thing. No one likes to be stuck on an endless project with no finish line in sight. Being in the trenches for nine months and not having anything to show for it is a real buzzkill. Eventually it just burns you out. To keep your momentum and motivation up, get in the habit of accomplishing small victories along the way. Even a tiny improvement can give you a good jolt of momentum.

The longer something takes, the less likely it is that you’re going to finish it.

Excitement comes from doing something and then letting customers have at it. Planning a menu for a year is boring. Getting the new menu out, serving the food, and getting feedback is exciting. So don’t wait too long—you’ll smother your sparks if you do.

If you absolutely have to work on long-term projects, try to dedicate one day a week (or every two weeks) to small victories that generate enthusiasm. Small victories let you celebrate and release good news. And you want a steady stream of good news. When there’s something new to announce every two weeks, you energize your team and give your customers something to be excited about.

So ask yourself, “What can we do in two weeks?” And then do it. Get it out there and let people use it, taste it, play it, or whatever. The quicker it’s in the hands of customers, the better off you’ll be.

Don’t be a hero

A lot of times it’s better to be a quitter than a hero.

For example, let’s say you think a task can be done in two hours. But four hours into it, you’re still only a quarter of the way done. The natural instinct is to think, “But I can’t give up now, I’ve already spent four hours on this!”

So you go into hero mode. You’re determined to make it work (and slightly embarrassed that it isn’t already working). You grab your cape and shut yourself off from the world.

And sometimes that kind of sheer effort overload works. But is it worth it? Probably not. The task was worth it when you thought it would cost two hours, not sixteen. In those sixteen hours, you could have gotten a bunch of other things done. Plus, you cut yourself off from feedback, which can lead you even further down the wrong path. Even heroes need a fresh pair of eyes sometimes—someone else to give them a reality check.

We’ve experienced this problem firsthand. So we decided that if anything takes one of us longer than two weeks, we’ve got to bring other people in to take a look. They might not do any work on the task, but at least they can review it quickly and give their two cents. Sometimes an obvious solution is staring you right in the face, but you can’t even see it.

Keep in mind that the obvious solution might very well be quitting. People automatically associate quitting with failure, but sometimes that’s

exactly

what you should do. If you already spent too much time on something that wasn’t worth it, walk away. You can’t get that time back. The worst thing you can do now is waste even more time.

Go to sleep

Forgoing sleep is a bad idea. Sure, you get those extra hours right now, but you pay in spades later: You destroy your creativity, morale, and attitude.

Once in a while, you can pull an all-nighter if you fully understand the consequences. Just don’t make it a habit. If it becomes a constant, the costs start to mount:

Stubbornness:

When you’re really tired, it always seems easier to plow down whatever bad path you happen to be on instead of reconsidering the route. The finish line is a constant mirage and you wind up walking in the desert way too long.

Lack of creativity:

Creativity is one of the first things to go when you lose sleep. What distinguishes people who are ten times more effective than the norm is not that they work ten times as hard; it’s that they use their creativity to come up with solutions that require one-tenth of the effort. Without sleep, you stop coming up with those one-tenth solutions.

Diminished morale:

When your brain isn’t firing on all cylinders, it loves to feed on less demanding tasks. Like reading yet another article about stuff that doesn’t matter. When you’re tired, you lose motivation to attack the big problems.

Irritability:

Your ability to remain patient and tolerant is severely reduced when you’re tired. If you encounter someone who’s acting like a fool, there’s a good chance that person is suffering from sleep deprivation.

These are just some of the costs you incur when not getting enough sleep. Yet some people still develop a masochistic sense of honor about sleep deprivation. They even brag about how tired they are. Don’t be impressed. It’ll come back to bite them in the ass.

Your estimates suck

We’re all terrible estimators. We think we can guess how long something will take, when we really have no idea. We see everything going according to a best-case scenario, without the delays that inevitably pop up. Reality never sticks to best-case scenarios.

That’s why estimates that stretch weeks, months, and years into the future are fantasies. The truth is you just don’t know what’s going to happen that far in advance.

How often do you think a quick trip to the grocery store will take only a few minutes and then it winds up taking an hour? And remember when cleaning out the attic took you all day instead of just the couple of hours you thought it would? Or sometimes it’s the opposite, like that time you planned on spending four hours raking the yard only to have it take just thirty-five minutes. We humans are just plain

bad

at estimating.

Even with these simple tasks, our estimates are often off by a factor of two or more. If we can’t be accurate when estimating a few hours, how can we expect to accurately predict the length of a “six-month project”?

Plus, we’re not just a little bit wrong when we guess how long something will take—we’re a lot wrong. That means if you’re guessing six months, you might be

way

off: We’re not talking seven months instead of six, we’re talking one year instead of six months.

That’s why Boston’s “Big Dig” highway project finished five years late and billions over budget. Or the Denver International Airport opened sixteen months late, at a cost overrun of $2 billion.

The solution: Break the big thing into smaller things. The smaller it is, the easier it is to estimate. You’re probably still going to get it wrong, but you’ll be a lot less wrong than if you estimated a big project. If something takes twice as long as you expected, better to have it be a small project that’s a couple

weeks

over rather than a long one that’s a couple

months

over.

Keep breaking your time frames down into smaller chunks. Instead of one twelve-week project, structure it as twelve one-week projects. Instead of guesstimating at tasks that take thirty hours or more, break them down into more realistic six-to-ten-hour chunks. Then go one step at a time.

Long lists don’t get done

Start making smaller to-do lists too. Long lists collect dust. When’s the last time you finished a long list of things? You might have knocked off the first few, but chances are you eventually abandoned it (or blindly checked off items that weren’t really done properly).

Long lists are guilt trips. The longer the list of unfinished items, the worse you feel about it. And at a certain point, you just stop looking at it because it makes you feel bad. Then you stress out and the whole thing turns into a big mess.

There’s a better way. Break that long list down into a bunch of smaller lists. For example, break a single list of a hundred items into ten lists of ten items. That means when you finish an item on a list, you’ve completed 10 percent of that list, instead of 1 percent.

Yes, you still have the same amount of stuff left to do. But now you can look at the small picture and find satisfaction, motivation, and progress. That’s a lot better than staring at the huge picture and being terrified and demoralized.

Whenever you can, divide problems into smaller and smaller pieces until you’re able to deal with them completely and quickly. Simply rearranging your tasks this way can have an amazing impact on your productivity and motivation.

And a quick suggestion about prioritization: Don’t prioritize with numbers or labels. Avoid saying, “This is high priority, this is low priority.” Likewise, don’t say, “This is a three, this is a two, this is a one, this is a three,” etc. Do that and you’ll almost always end up with a ton of really high-priority things. That’s not really prioritizing.

Instead, prioritize visually. Put the most important thing at the top. When you’re done with that, the next thing on the list becomes the next most important thing. That way you’ll only have a single next most important thing to do at a time. And that’s enough.

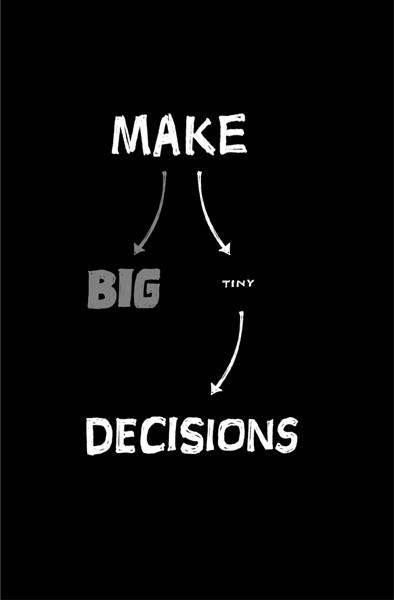

Make tiny decisions

Big decisions are hard to make and hard to change. And once you make one, the tendency is to continue believing you made the right decision, even if you didn’t. You stop being objective.

Once ego and pride are on the line, you can’t change your mind without looking bad. The desire to save face trumps the desire to make the right call. And then there’s inertia too: The more steam you put into going in one direction, the harder it is to change course.

Instead, make choices that are small enough that they’re effectively temporary. When you make tiny decisions, you can’t make big mistakes. These small decisions mean you can afford to change. There’s no big penalty if you mess up. You just fix it.

Making tiny decisions doesn’t mean you can’t make big plans or think big ideas. It just means you believe the best way to achieve those big things is one tiny decision at a time.

Polar explorer Ben Saunders said that during his solo North Pole expedition (thirty-one marathons back-to-back, seventy-two days alone) the “huge decision” was often so horrifically overwhelming to contemplate that his day-to-day decision making rarely extended beyond “getting to that bit of ice a few yards in front of me.”

Attainable goals like that are the best ones to have. Ones you can actually accomplish and build on. You get to say, “We nailed it. Done!” Then you get going on the next one. That’s a lot more satisfying than some pie-in-the-sky fantasy goal you never meet.

*

Dave Demerjian, “Hustle & Flow,”

Fast Company

,

www.fastcompany.com/magazine/123/hustle-and-flow.html

†

“Maloof on Maloof: Quotations and Works of Sam Maloof,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/online/maloof/introduction