Richard The Chird (15 page)

Authors: Paul Murray Kendall

BARNET

fled from the field, and the Earl galloped northward for the safety of Scotland.

Ignorant though he was of the cause of this commotion, King Edward realized that his opportunity had come. With the whole of his reserve he smashed at the center of Warwick's line.

Of all this Richard, far out on the eastern edge of the plateau, knew nothing. Dangerously his line swayed back and forth, his soldiers fighting bitterly to maintain themselves atop the hill' He possessed no fresh troops. Edward's precious reserve he could not bring himself to deplete. He was grimly staking everything on the men who, a lifetime ago, had charged with him out of the hollow. His second squire had now been killed at his side; he himself was slightly wounded.

^ Suddenly, there was a swirl in the mist to the left of and behind the enemy's position. A shiver ran down the Lancastrian line. Exeter's men began to give way, stubbornly at first, then faster. Warwick's center must be crumbling. Richard signaled his trumpeters. The call to advance banners rang out. The weary young commander and his weary men surged forward. The hedge of steel before them began to fall apart. Then the enemy were in full flight, casting away their weapons as they ran.

Out of the mist loomed the great sun banner of the House of York. A giant figure strode forward. Pushing his visor up, Richard saw that the King was smiling at him in brotherly pride. The right wing, driving westward across the Lancastrian rear, had linked up with Edward's center to bring the battle to an end. It was seven o'clock in the morning; the struggle had lasted almost three hours.

The men of Montagu and Warwick had not been able to withstand the shock of Edward's great blow. After a brief, bitter resistance, they had broken and fled. The Marquess fell slain— fighting bravely for his brother, some said; others claimed that the Lancastrians, detecting or suspecting his treachery, had killed him; still others, that though he gave battle under Warwick's banner' he wore beneath his harness the colors of the King. It is quite probable that John Neville, caught in a hopeless conflict of loyalties, had determined not to survive the field. Only thus, perhaps,

could he save the bird in his bosom. When Warwick learned that Oxford was fled, his brother slain, and his line crumbling, he lumbered from the battle in his heavy armor toward Wrotham Wood, where his horses were tethered. Overtaken by pursuing Yorkists, he was killed before the King could intervene. 7

Early in the afternoon Edward led his army in triumph back to London, his brother Richard riding by his side. Next morning, the bodies of the Kingmaker and the Marquess, naked but for loincloths, were conveyed to St. Paul's cathedral, where they lay for two days upon the pavement that the end of the House of Neville might be known to all. 8 *

Tewkesbury

Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths

ONLY just in time had Edward and Richard settled accounts with Warwick. On the very day of Barnet, Queen Margaret had landed at Weymouth with Prince Edward and his wife, Anne Neville, and gone to Cerne Abbey. There the Duke of Somerset and the Earl of Devon met her shortly after with the news of Warwick's overthrow.

When the Countess of Warwick, who had sailed to Portsmouth, heard the tidings, she fled to sanctuary in Beaulieu Abbey; but Queen Margaret, though at first terribly shaken by the blow and filled with fear for the safety of her son, was at last persuaded by Somerset that King Edward had been fatally weakened and that victory was hers for the taking. As the Queen's party moved to Exeter and then to Taunton and Wells, the gentry of Devon and Cornwall came streaming in, and Somerset, Dorset, and Wiltshire likewise rallied in numbers to her banner.

Two days after Barnet, on Tuesday, April 16, word of the Queen's landing reached London. Richard and the other commanders set instantly to work to assemble a fresh army; the King summoned men from far and wide to meet him at Windsor, and borrowed money from his loyal Londoners. While he was celebrating the Feast of St. George (April 23) at Windsor Castle with his brothers and his captains, Edward learned from his scouts that though Margaret had made a feint in the direction of London, she was probably on her way to join Jasper Tudor in Wales. The King set off next day in wary pursuit. On Tuesday, April 30, at Malmesbury he was informed that the Lancastrians, marching north from Wells through Bath, had turned westward to enter Bristol. Margaret's commanders had, in fact, underestimated the King's speed of advance. On Thursday, May 2, they issued

"5

hastily from Bristol. Making a pretense of preparing to give battle on Sodbury Hill, they marched as fast as they could up the Severn valley. To escape into Wales, they had to reach the bridge at Gloucester before the King overtook them.

Edward arrived on Sodbury Hill that same afternoon. Finding no enemy, he encamped his army and anxiously sent out scouts. At three o'clock on Friday morning they galloped into the sleeping camp to report that Margaret's army was racing through the night toward Gloucester. Edward dispatched word to the governor of the town that he must hold out at all costs against the rebels. Richard and Hastings and the other commanders roused their men. Through the darkness the army started in pursuit of the fleeing enemy.

When the Queen reached Gloucester at ten o'clock on Friday morning, she discovered the gates of the city barred and soldiers manning the walls. Not daring to pause for an assault—for she now knew that Edward was on her trail—Margaret frantically drove her weary host northward toward Tewkesbury, the next possible crossing of the Severn.

A grim race now ensued. The day was hot. The Queen's footsore and dusty soldiers struggled through "a foul country, all in lanes and stony ways, betwixt woods, without any good refreshing." Not far behind and a little to the east of them in the rocky upland, Edward, Richard, and Hastings urged their army forward, on roads no less difficult. The men could "not find, in all the way, horse-meat, ne man's-meat, ne so much as drink for their horses, save in one little brook, where was full little relief, it was so soon troubled with the carriages [carts] that had passed it. And all that day was evermore the King's host within five or six miles of his enemies; he in plain country and they amongst woods; having always good espials upon them." x *

When the Lancastrians reached the outskirts of Tewkesbury about four o'clock in the afternoon, the foot soldiers threw themselves upon the ground in utter exhaustion. The Queen's commanders informed her that neither men nor horses could go another step. In an agony of fear for her son, Margaret was forced to turn at bay.

As the modern road from Gloucester to Tewkesbury passes Gupshill Inn, less than a mile south of the town, it cuts through the heart of the Lancastrian position. The Queen's forces dragged themselves into battle array on an irregular line of high ground, bounded on the left by a stream called Swillbrook and on the right by a wooded knoll. The position ran roughly east and west "m^a close even at the town's end; the town, and the abbey, at their backs; afore them, and upon every hand of them, foul lanes, and deep dykes, and many hedges, hills, and valleys, a right evil place to approach, as could well have been devised." Though this position appeared to be as formidable in its way as the massive Norman tower of Tewkesbury Abbey rising directly to the rear, it was exposed to one ominous hazard: not far behind the right wing, northwestward down a slope of meadow, the river Avon flowed to its confluence with the Severn.

So hot were the Yorkists upon the trail that when they reached Cheltenham, but nine miles from Tewkesbury, Edward learned that "his enemies were come to Tewkesbury, and there were taking a field. Whereupon the King . . . a little comforted himself and his people, with such meat and drink as he had done [caused] to be carried with him ... and, incontinent, set forth towards his enemies ... and lodged himself, and all his host, within three mile of them."

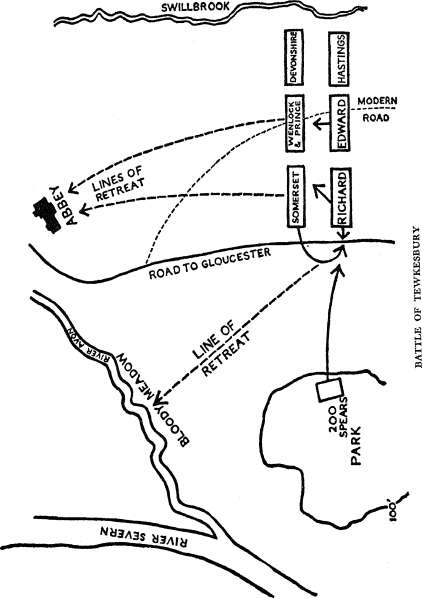

Early next morning Richard of Gloucester, again commanding the vanguard, marched northwestward across this inhospitable •country to take up a position facing the Duke of Somerset on the Lancastrian right wing. The King followed his brother into the center of the line, opposite Prince Edward, the son of Margaret, and Lord Wenlock, the friend of Warwick. Hastings, with the rear guard, filled up the position to the right until his'flank touched the Swillbrook.

Richard at once led an assault, but the "foul lanes" and many hedges made it impossible for him to get at the enemy. There followed a fierce exchange of arrows, with some cannon fire. Then Somerset, perceiving that his foes were checked, decided upon a bold stroke. Concealed by the hedges and thickets, he led his army westward to the slope of the wooded knoll and charged

down upon the Yorkist left flank. Coolly Richard rallied his men. Though they gave some ground they did not fall into panic. Once he and his captains had reformed their line to face Somerset, they pressed the attack so vigorously that the Lancastrians began to fall back. At this moment a small band of spears, whom King Edward had stationed on the knoll for just such an emergency, descended upon Somerset's rear, shouting as if they were an army. Confused by this diversion and shaken by the fierce assault of the Duke of Gloucester, Somerset's men wavered, then broke in headlong flight toward the Avon. The pursuit which followed has given the name of "Bloody Meadow" to this ground.

When Edward perceived that his brother had routed the Lancastrian right wing, he himself attacked the center, while Richard swung round upon its now unprotected right flank. As Prince Edward was experiencing his first bitter taste of battle, the Duke of Somerset rode up to Lord Wenlock in a fury, cried that Wen-lock had deliberately betrayed him by not supporting his flank attack on Richard's wing, and with a single blow of his battle-axe cleft Wenlock's skull. Beholding their leaders butchering each other as King Edward and the Duke of Gloucester splintered their line, the Lancastrian center crumbled into flight. Many were drowned trying to cross the Avon; many fell beneath the swords of the closely pursuing Yorkists; some hid themselves in the abbey or the town. Swept away by the rout and spurring toward Tewkesbury in terror, Prince Edward was overtaken by a detachment commanded by the Duke of Clarence. Though the youth cried for succor to the man who had shortly before been his ally, he was immediately slain. Clarence was no doubt eager to assert his new-found loyalty. 2 *

A few moments later the King came storming up to the abbey doors. The abbot confronted him, pleading that he not defile a holy place. Regaining his temper, Edward not only consented but in a hasty moment offered his pardon to the soldiers who had sought shelter there. When he discovered, however, that Somerset himself and his chief captains were within, he determined to seize them. After he had generously tried to make a friend of Somerset's brother in 1463, the ungrateful Beaufort had betrayed him

at the first opportunity. The abbey was not a specially privileged sanctuary. By the standards of the century the rebel leaders had no reason to expect anything but death; and policy dictated to the King that he must break his hastily given word in order to rid the realm of these inveterate troublers of the peace. On Monday, May 6, Somerset and about a dozen others were taken from the abbey and tried before Richard of Gloucester, Constable once again, and the Duke of Norfolk, Marshal of England. Sentenced to death, the rebel leaders were immediately beheaded in the market place of Tewkesbury. 3 *

King Edward and his army now proceeded to Coventry, where both good news and bad greeted them. A rising in the North had been easily quelled, but the Bastard of Fauconberg was attacking London. At this moment Queen Margaret, captured in a house of religion not far from Tewkesbury, was brought in. It was only a husk they had taken, the shell of a woman and the shadow of a queen. That dauntless spirit had been crushed at last by the news of her son's death, which had been broken to her by her captor, Sir William Stanley, with brutal relish. Lifelessly, she was borne along in King Edward's train as he took his way rapidly toward London to meet the final Lancastrian threat.

It was less serious than it first appeared. Having assembled a mob of Kentishmen, the Bastard bombarded the city with artillery placed on the south bank and attacked some of the gates; but the Earls of Rivers and Essex drove his men back by sudden sallies, the Londoners defended themselves valiantly, and when a small advance guard of the King's army arrived, Fauconberg fled to his fleet at Sandwich.

On Tuesday, May 21, King Edward entered his capital in the full panoply of victory—trumpets and clarions sounding, battle flags streaming above his troops. The honor of heading this triumphal procession was bestowed upon Richard, Duke of Gloucester. He was followed by Lord Hastings and then by the King himself; toward the rear came the Duke of Clarence and finally the drooping figure of Queen Margaret seated in a chariot.

That evening the King held a conference of his advisers, at the conclusion of which he sent the Constable of England, his brother

Richard, with a delegation of noblemen to bear an order to Lord Dudley, Constable of the Tower: that feeble candle, the life of Henry the Sixth, was to be snuffed out. His death must bring to an end, it seemed, the convulsions of civil strife which had so long shaken the realm. The next night Henry's body, surrounded by torches and a guard of honor, was borne to St. Paul's, where it lay upon a bier, the face uncovered. Shortly after it was transported up the Thames to be entombed in the Lady chapel of Chertsey Abbey. 4 *