Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (30 page)

Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

I want to tell you this calamitous tale not necessarily objectively (for human objectivity, like ghosts, is possible only in theory and has even less substance than a Nodgort) but at least accurately and evenhandedly, although when I reach the conclusion, I’ll have to interpret. The story, one I’ve long wanted to relate, was earlier impossible to me because I didn’t have the details until Q, an investigator of no mean order, began dragging them into the light, a ghostly light. Or perhaps I mean the light of ghosts. I am, in a sense, a participant in this crime, and my life has been turned a certain way because of those occurrences in 1901. While you read the next some pages, your life too will be participant.

By the end of its first quarter century, Joplin, Missouri, was a mining community on a rapid clip toward high prosperity, a lead and zinc boomtown full of situations and characters commensurate with such development. Any place whose early history contains a Three-Finger Pete and a county coroner surnamed Coffin is bound to have a past as lively as it is deadly. What cattle were then doing to Dodge City (not far westward), metals were doing in Joplin. We all know, in America, ore cannot be taken from the ground below without the assists of saloons, games of chance, and houses of ill fame on top of it. When such gathered enterprises lie within a gallop of two “dry” states and an alcohol-prohibited Indian Territory, booze will determine things as rainfall does a forest. The usual lubricant of a spinning roulette wheel or a bordello is alcohol, and without it, mechanical rotations and purchased pleasures tend to come to a frictioned, squeaking halt.

One of Joplin’s folk historians, Dolph Shaner, wrote in 1948 of that town named after a Methodist preacher:

Several decades ago, when a crusade was being organized, one of the speakers libeled the city as being as bad “as Babylon with its hanging gardens.” But it wasn’t that bad. There were saloons, gambling places, assignation houses, and bawdy houses. Time was when a circus parade brought faces of dozens of female denizens to upstairs windows along Main Street.

Those denizens, of course, were not one-flight-up dentists or lawyers or even typists; their profession was older, at least as old as hanging gardens. A man was to tell me, “Fourth and Main in nineteen hundred was a place a miner could come up above ground to wet his whistle

and

his weasel until his Saturday wages were gone.”

At that intersection of Fourth and Main — the topographic, political, and social heart of town, the location where north-south electric trolleys crossed east-west lines — stood the two best hotels: the three-storey Joplin (the center of the “brick hotel ring”) and the newer, eight-floor Keystone built by a Pennsylvanian and therefore not a component of an oligarchy I shall soon speak of. On opposite corners were the Worth Building and its aptly named House of Lords Restaurant and Bar at street side, with a gambling den on the second floor and a flesh parlor on the third. Catercorner stood a two-storey, ramshackle frame building that had been moved fifteen miles by mules across the Kansas border in 1873, the year of the official founding of Joplin. On its upper floor were blossoms in a hanging garden, and at sidewalk level was the Club Saloon where, a few years before our year in question, a fatal shooting happened.

(Here’s a little incident from about 1900 to help set the tone for events to come: An attractive guest in one of the Main Street hotels arrived in Joplin by train. She was selling encyclopedias. Aware that a mining town is only slightly more literary than, say, a mine shaft, she had learned how to circumvent such unlettering. Counting on her shapeliness to gain entry to a businessman’s office, she would pointedly mention her wish to see the beauty of the countryside:

If only she had a buggy — perhaps at eleven on Tuesday morning.

At that hour on that day in front of her hotel, the number of shined buggies with men, mustaches waxed to perfection and hat brims dashingly rolled, was unusual. At half past eleven, one expectant blade went inside to inquire after the bookish miss. “What!” said the clerk. “Why, she caught the evening train for points west last night!” Evidence of this story may be the large number of unsoiled encyclopedias showing up at estate sales a few years later.)

In 1924 Joplin became so desirous of cleaning itself up it prohibited “cheek-to-cheek dancing, extreme side-stepping, whirling, dipping, dog walking, shuffling, toddling, Texas tommying, the Chicago walk, the cake-eater or Flapper hop, and stiff-arm dancing.” Whether you might be cited in Joplin eighty years later for, say, an excessive side step or a bit of toddling, I don’t know, but I do know the city is no longer much of a mining town or particularly “wide-open.” Where once stood the House of Lords Restaurant and Bar and its upstairs sportations is a pocket park not of wetted whistles and weasels but of birdsong and squirrels. At the time Q and I were at the historic crux of Joplin — accurately depicted in Thomas Hart Benton’s mural in city hall — words like

tavern

and

saloon

were in some circles almost as coarse as

whorehouse,

and it took me three inquiries in the library to learn the location of the nearest spirituous beverage, although it was only a block away in a restaurant I’ll call the Blue Tomato.

It is not digressive, as you will see, to mention here a sign, partly overgrown and showing decay, I saw on the north end of Main Street. The hand-painted words came from Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man”:

Vice Is A Monster Of So Frightful Mien,

As, To Be Hated, Needs But To Be Seen,

Yet Seen Too Oft, Familiar With Her Face,

We First Endure, Then Pity, Then Embrace.

For a pint and a quiet place to discuss ghostly histories emerging before us, Q and I walked a block east of Main to the Tomato, a pleasant establishment free of hard spirits, as one might guess from cash-register receipts imprinted with

“SERVING JOPLIN IN JESUS NAME!”

Ignoring the beloved American Aberrant Apostrophe (the one on the tab having wandered from the register and out the door to end up down the street on a

CLOSED MONDAY’S

sign), I asked our “server,” Jessie, a bubblelating young blonde, about the slogan. She said, “What slogan?” After she poured our glasses of ale, I mentioned to Q the catchphrase had me hoping to have service from the Anointed Himself, and Q responded, “How do you know you didn’t?” Alert the tabloids:

JOPLIN JESUS, AKA JESSIE, SPOTTED SERVING SUDS.

Once again, humoring reader, my tale wanders from its path. But then, as Master Tristram Shandy says, “Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine, they are the life, the soul of reading: — take them out of this book, for instance, you might as well take the book along with them.” But that was long ago, and my editors believe contemporary readers to be less tolerant, so I’ll return to the story fully mindful, nevertheless, that service to the House of Lords — and to the Anointed Lord Himself — lies quite within this dark matter. Perhaps I should begin there.

A Poetical History of Satan

W

ILLIAM GRAYSTON

, born 1862, came with his family soon after the Civil War to near Sparta in Christian County, Missouri, on the edge of the northern Ozarks, about eighty miles east of Joplin. The county took its name not because it was rich with fact-free fundamentalism but rather from a district in Kentucky bearing the surname of a Revolutionary War soldier killed by Indians. That Missouri area, even with its ardent foot-washing Baptists, was a hotbed of vigilantes: at a public hanging, praying over one of them on the scaffold was William’s father, David, an English immigrant stonecutter who made his way west by finding work along the Erie Canal. Once in southern Missouri, David discovered he could outpreach, outwrite, and outdebate any ordinary Methodist, Presbyterian, or Freethinker daring to take him on.

He wrote “A Poetical History of Satan,” “Poetic Rambles in Search of the Church,” “Millennium,” and

The Poetical Bible

wherein (if you can imagine it) he set the entire holy writs from Genesis to Revelation into couplets, that least tolerable of rhymes. He and his brother-in-law, B. J. Wrightsman, at someone’s behest, composed “Missouri” and offered it as the official state-song; after a performance in the capitol concluded with an ovation, the tune vanished, except for my copy of the sheet music in Q’s piano bench. From time to time she pulls it out to amuse me with its notably unanthemic melody, although it’s something you could shake a jolly bustle to. As for David Grayston’s

Poetical Bible

and his history of Old Clootie, I’ve never succeeded in finding those.

William grew up in a household thick with sermons from a brilliant if aloof father, a man who was (wrote the

Joplin Daily Globe

in 1901) “a power in shaping both the religious and political destiny of Southeast Missouri.” Young Willie, a handsome boy of acute intellect, took in the religionizing designed more to prove fallacies in other sects than to set forth its own theosophical base interpreting existence. The earthly task of humankind, so he heard repeatedly, was to acquiesce and simply believe; after all, things would be explained later in the beyond. But the presumed superiority of willful incognizance over freedom of inquiry made no sense to him. If a Creator gave intelligence and the power to inquire and discover truths, why would It then insist on beliefs demanding blind faith?

The boy wondered whether life eternal could be bought with nothing more than a mindless, even uncomprehending, confession of sin preceding a profession of “I believe.” Didn’t such mindlessness make escape from one’s own iniquities easy while minimizing — if not negating — the significance of good works? Could a mass murderer do a confess-and-profess and thereby earn eternal redemption while a freethinking physician who healed thousands would be forever damned? How could such a concept advance humanity? What kind of god would encourage blind faith to trump mercy and generosity? Wasn’t a quest for “personal salvation” the ultimate expression of self-concern?

Moving gradually away from a religiosity emphasizing iniquity over inquiry, piety over percipience, William learned to orate rather than preach, and as he came into manhood, he found his principles of morality and ethics, of social justice and public duty, residing far more in humanity itself than in deity. If such a thing as heavenly redemption existed, it would not be through a declaration of belief that can evaporate in a moment — it would be through kindly works which can long remain markers of one’s life. He began to comprehend the greater challenge — and risks — in bringing people to reason rather than merely to belief. For him, the way to a better life for all was to be discovered through the light of examination rather than through unquestioning faith. His means were inductive thought and scientific method. As his father would later sadly write of his son:

Darwin and Spencer his guide

Instead of Jesus crucified.

Young Grayston wasn’t afraid of the demanding effort of seeking a spirituality based not on supposition, strictures, credulity, and dogmatized opinion but rather upon a close reasoning leading to consequent service to other people. His sacred texts became the writings of Thomas Huxley and Charles Darwin and especially Herbert Spencer (“struggle for existence,” “survival of the fittest”). In 1901 the

Globe

was to write of William: “He knew as much about the contents of

On the Origin of Species

and

The Descent of Man

as anyone in the state of Missouri perhaps. . . . No phase of either physical science or speculative thought escaped his attention.”

Grayston was a man in search of evidence wherever it lay, and that led him into law after finding a congenial example in attorney and orator Robert Ingersoll of New York, another preacher’s son whose freethinking, rationalistic speeches — “Why I Am an Agnostic,” “Some Mistakes of Moses,” “Superstition” — may have kept him from running for the Presidency. (Or maybe it was quips like “With soap, baptism is a good thing.”)

The relation between the son and his biblically doctrinaire father grew strained, especially so when Will went westward to the new colony of Freethinkers in Liberal, Missouri, thirty miles north of Joplin. For a short spell, at age twenty-three he became the principal of the school soon to grow into Free Thought University in (said opponents) “a godless town” having neither churches nor saloons, where the freethinking residents said they kept “one foot upon the neck of priestcraft and the other upon the rock of truth.” In Universal Mental Liberty Hall, Will listened to or lectured or debated all who came: scientists, Baptists, atheists, Jews, deists, Catholics, or anyone else of capable mind willing to observe the lone rule of maintaining “respectable decorum.”

Such a place, of course, drew the ire — if not fear — of certain intolerant Christians who could see it only as “a practical experiment in Infidelity” and who condemned and cursed anyone associated with it. (On the day Q and I visited Liberal — population seven hundred, about the same as it was in Grayston’s day — the major change since then, as far as I could determine, was there were now only two “liberals” anywhere about and, according to certain laws of physics, the pair of them departed town at the same moment and in the same vehicle as did we.)

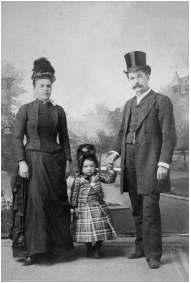

Soon after the founder of Liberal and Free Thought University abandoned inductive process and descended into spiritualism, Grayston returned to his home area near Springfield where he married and became the father of Gertrude who bore her sire’s intellect but not his internal strength. (I name her because she will appear again in this story.) After the birth of a second child, Herbert (for philosopher Spencer), the mother struggled with what appears to have been postpartum depression exacerbated by the death of little Herbert in infancy.