Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (42 page)

Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

That menu suggested Jean was a vegetarian, but she allowed herself “several small bites of meat, poultry, or fish once a day — just enough to sample the flavor and texture.” But later she said, “Meat-eating is on a collision course with human population. Increasing human numbers will make every problem facing us insoluble. But it’s an unusual organization today that will even mention overpopulation, especially the big environmental groups.” On that topic, I said, they’ve lost their courage to talk about a world populace increasing by more than two-hundred-thousand humans

every day.

Until humanity decides to get a grip on its deadly proliferation, nothing — no other problem — can be solved. She considered, then said, “I’m afraid we’re going to let things slide so long, forced sterilization will become necessary.”

Ingold was carrying a plastic trash bag folded small; on her return home, she would walk through Alameda Park: “I don’t go to picnic — I go to pick up. I like to think, wherever I live, the neighborhood looks better after a few of my walkabouts.” That reminded her: “When I was in your town a few years ago, a man in a new car saw me picking up litter, and stopped and tried to hand me twenty dollars. He was terribly insistent.” Was he buying off his conscience the way people do the homeless? She said, “Maybe it was just a thanks. I get them sometimes.”

Although she would, from time to time, check for forgotten change in the coin return of a public phone, she usually would not accept money offered her. It was more than a matter of pride: refusing money in America gets remembered along with — she hoped — the act of somebody doing a lowly task to upgrade the public weal without being paid for it beyond recognition (even if sometimes of a disdainful sort). Yet in her was no self-congratulation, no sanctimoniousness about a fearless lone-woman stewardship. She was doing simply what she wanted to do.

In spite of her always being alert to her appearance and never looking unkempt, always keeping her thrift-shop outfits neatly coordinated, her litter sack could nonetheless cause people to take her for a bag lady, a judgment making it easy for them to explain her to their convenient satisfaction. After all, where’s the pigeonhole for an educated and attractive woman working alone to clean up after the rest of us? Ingold did not mention it, but I saw it: an occasional person deprecating and depreciating her efforts, palliatives against anyone disturbing the smugly comfortable who are incapable of considering two words —

rethink excess.

At one point, Jean stepped off to pick up a couple of beverage containers — an aluminum one to resell, but the plastic one in Alamogordo was only trash. I watched her small buckskin moccasins leave ever-so-faint imprints in the dusty alley. There was a woman who had walked away — steadily if slowly — from a life of artificial wants made to look like needs. She would never speak of it this way, but I will: Jean Ingold’s monkey wrench of nonconformity was tiny, but she never hesitated to throw it into the greased machinery of crapulent consumerism.

I had no plan to live exactly as she did, in part because she depended on the overflow of a prodigal nation. What I saw in her life was an alert to superfluity, a demonstration of the ancient and universal wisdom of controlling material desires by enhancing the life of one’s heart and mind, the grand goal of every major religion and spiritual path ever put before humanity. Perhaps I’m unaware of one, but I can’t recall any way of the spirit that demands perfection (Matthew’s “Be ye perfect” gets a better reading from Luke: “Be ye merciful”). Most of the paths, it seems to me, say more simply, “Wake up! Do better! Connect!” Ingold’s habits set a marker to measure how near or far I might be from such a course, how close to a broadly sensible material existence. For me, the mirror she held up reflected not so much her achievement as the distance I believed I had yet to go. Her life was a burr in my conscience, and I was in her debt for it.

Before he died, her father wrote twenty-seven-year-old Jean to urge her to

choose

a life she wanted rather than to merely drift into one. Said he, a former analyst with the Securities and Exchange Commission, “I would not advocate as a supreme goal a comfortable, affluent life in the suburbs. Even poverty itself would not be bad if you were making some sacrifice for an ethical objective. But sheer, purposeless poverty I can’t accept.” Forty years later, I believe Father Shirer would accept his daughter’s walking away from a pampered life and the emptiness of possessions into a fulfilling one of considered and deliberate frugality.

The night before I said good-bye to her, I was up in the foothills near La Luz, with the Sacramentos at my back. I looked across the Tularosa Basin to watch for a new weapon of luminescence to get shot up toward the Oscura Mountains. Somewhere out there under the white gypsum sands was the ancient lake the old inhabitants foresaw one day rising again, and southward was Lake Lucero, now a dusty alkali barren waiting for rain, a withered flat more like a fallen Lucifer than the Morning Star. I was straining to see into the dusk, as if my vision were impaired.

Down there too were Jean Ingold’s 117-square-feet sitting on the edge of a vast field of lights and darks, some natural, some humanly made, some of beauty, some of terror. Perhaps it was her proximity to that Armageddon that made me remember another of the adages she liked:

After your fuse blows, let your light shine.

A day earlier, hearing herself say it, Jean looked at me and said, “But do we even have fuses anymore?”

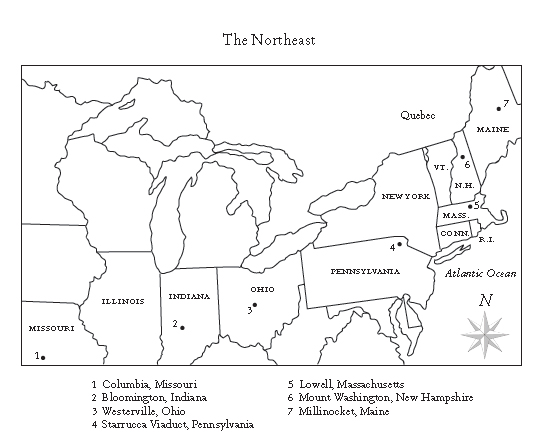

Into the Northeast

Into the Northeast

On Motoring

329

1. In Hopes Perdurable Reader Will Not Absquatulate 331

2. Hoisting Jack 336

3. Spontaneous Bop 345

4. Ten M To B 352

5. Building a Time Machine 358

6. Finding the Kaiser Billy Road 366

7. A Tortfeasor Declines to Take a Victim 375

8. Forty Pages Against a Headache Ball 385

9. No More Than a Couple of Skeletons 393

10. What Raven Whispered 403

On Motoring

Considering the fixation of the American people upon automobiles and their use, there has been surprisingly little of what might be called personal or imaginative writing on the subject. In the first decade of the century, C. N. and A. M. Williamson delighted the reading public with a series of novels under such titles as

The Motor Maid,

and

The Car of Destiny.

But since that time has there been a novel based chiefly on motoring?

— George R. Stewart,

U.S. 40: Cross Section of the United States of America,

1953

In Hopes Perdurable Reader

Will Not Absquatulate

N

OW THAT OUR TRAVELS

have reached beyond the halfway mark, perdurable reader, it occurs to me I’ve not yet said anything about the subtitle of this book and its key word,

mosey.

Maybe you first heard the term from the mouth of a bewhiskered, hornswogglin bullwhacker in some B Western: “I reckon I’ll just mosey on.”

But you’ll note I’ve turned it into a noun about jogging along literally and figuratively, the destinations little places in the nation or in a notion. It’s a mosey because roads to quoz everywhere are posted “reduced speed ahead.” To hurry, in space or idea, is to miss obscured signposts, hidden turnoffs, or an exit to Sublimity City (Kentucky), or Surprise Valley (California), or even Dull Center (Wyoming). To go leisurely today is almost un-American, so putting

mosey,

a pure Americanism, into the title of a book about America verges on illogic and invites mocking from any citizen carrying a fastport issued by the Department of Speed in a nation hell-bent for destination if not destiny in the Posthaste Era:

[

TO BE READ

PRESTISSIMO

] Speedy drive-up window, speed-dialing, speed-reading, speedball, speed freak, speedway, Speedy Gonzales

Andale-ándale,

immediate access, no waiting, call now — don’t wait, now’s the time, haven’t got the time, hasty decisions, hasty pudding, short orders from a fast-food window, quick lunch and make it snappy, quick stops, quick time, quick count, quick-change artist, quick and dirty, a quickie, double-quick, on the double, be there in a jiff, jiffy copies, instant coffee, instant cash, instant winners, instant replay, instant stardom, overnight success, overnight express, nine-day wonder, fifteen minutes of fame, ten-minute manager, five-minute rice, minute steak, a minute’s all I got, flash-fried clams, flash-dried potatoes, flash drive, in a flash, greased lightning, like a blue streak, express lane, fast lane, fast track in the rat race, fast-talking hustler, fast freeze, fast breeder reactor, can’t hit the fastball, faster than a speeding bullet

Upupandaway,

zip, zoom, whiz, lickety-split, in nothing flat, in less than no time, a rolling stone gathers no moss, don’t let the grass grow under your feet, make tracks, step lively, step on it, shake a leg, hotfoot it, hightail it, pick ’em up and set ’em down, get in and get out, get the lead out, pour it on, put it in high gear, put the pedal to the metal, run it wide open, ball the jack, highball it, full speed ahead, full steam, full throttle, full blast, hauling ass, barrel-assing, going like ninety, eat my dust, now you see me — now you don’t, Road Runner

Beep-beep,

going like mad, going like a house afire, speed maniac, speed demon, a bat out of hell, hell-bent for leather, only green lights on god’s highway, never look back — something might be gaining on you, here today — gone tomorrow.

[

TO BE READ

ADAGIO MOLTO

] On the dead run until you reach the finish line where six pallbearers will carry you at a funereal pace to your six-feet-under to spend eternity at Dead Slow.

These wanderings into quoz are a mosey because they took three years and four seasons to accomplish their sixteen-thousand miles of journeys to places a goodly portion of the American populace would call “nowhere.” But I believe simply

lighting out for the territory,

to crib Huck Finn’s words, carries its own sweet justification; to lift another phrase, you might see it as a

because-it’s-there

approach to exploration. In a hundred ways, America is where it is because its people can be maniacally destination-bound; America is where it isn’t for the same reason. Some of us find that a pleasant circumstance.

I’ll add here, also somewhat belatedly, any reviewers attempting to find a thesis in these pages will be summarily barred from their writing machines until able to state clearly and concisely

the

thesis of their lives. Meanings, of course, are another matter. More life happens on the way to the forum than

in

the forum, and there’s a word relevant to that phenomenon:

circumforaneous,

the strolling from forum to forum. Whether we like it or not, for better or worse, we all live circumforaneous lives, and that’s why this is a circumforaneous book.

The word

mosey,

as does

vamoose,

probably derives from the Spanish

vamos,

“we go.” Some lexicographers offer, however, the possibility it descends from nineteenth-century itinerant Jewish peddlers often named (or pejoratively called) Moses; other scholars find its origin in the leisurely and relaxed gait of antebellum, Southern Negroes (“Mose” a not-uncommon moniker) who had little to gain by hurrying to the hot fields. The earliest theory I’ve seen comes from John Russell Bartlett in his wonderfully jolly (although I think not so intended)

Dictionary of Americanisms

of 1848, which contends the word

mosey

(he termed it “a low expression”) derives from an Ohio postmaster named Moses who absconded with considerable federal receipts. But absconding is no longer — if it ever was — at the heart of moseying.

A better term, by the way, for such flight, coincidentally one I learned from Bartlett’s lexicon, is

absquatulate.

He cites an illustration of its usage:

Hope’s brightest visions absquatulate with their golden promises before the least cloud of disappointment, and leave not a shinplaster behind.

(A

shinplaster

here, as Bartlett explains under that entry, is “worthless currency.”)

I sometimes read his dictionary as if he intended it to be compendious stories of mid-nineteenth-century life; you need only fill in details between his entries and definitions to see yarns and anecdotes emerge from obscurity like a

mud-pout

(catfish) caught by a

sneezer

(thoroughgoing fellow) lazily smoking his

loco-foco

(self-igniting cigar). That last word carries a five-hundred-word micro-essay I’m tempted to pass along, but editorial judgments suggest I leave certain things to your own further explorations. Bartlett’s citation for

sneezer,

however, I’ll give to you because I gave it to Q:

It’s awful to hear a minister swear; and the only match I know for it is to hear a regular sneezer of a sinner quote Scripture.

She, who often says more with a glance than with words, thereby making it difficult to quote her, considered that sentence, then looked at me, her silence louder than necessary.