Roosevelt (27 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

Tension was rising, especially in the Far East. The imperial rebuke spurred Konoye to redoubled efforts at diplomacy even as the imperative timetable compelled generals and admirals to step up their war planning. The government seemed schizophrenic. All great powers employ military and diplomatic tactics at the same time; but in Japan the two thrusts were competitive and disjointed, with the diplomats trapped by a military schedule.

Subtly, almost imperceptibly, Konoye and the diplomats beat a retreat in the face of Washington’s firm stand. Signals were confused: Nomura acted sometimes on his own; messages were also coming in via Grew and a number of unofficial channels; and Konoye and Toyoda had to veil possible concessions for fear extremists would hear of them and inflame the jingoes. The Japanese military continued to follow its own policies; amid the delicate negotiations, Washington learned that the Japanese Army was putting more troops into Indochina. The political chiefs in Tokyo, however, seemed willing to negotiate. On the three major issues Tokyo would: agree to follow an “independent” course under the Tripartite Pact—a crucial concession at this point, because America’s widening confrontation with Germany raised the fateful possibility that Tokyo would automatically side with Berlin if a hot war broke out; follow co-operative, nondiscriminatory economic policies, a concession that was as salve to Hull’s breast; and be willing to let Washington mediate a settlement between Japan and China.

Day after day Hull listened to these proposals courteously, discussed them gravely—and refused to budge. He insisted that Tokyo be even more specific and make concessions in advance of a summit conference. By now the Secretary and his staff conceded that Konoye was “sincere.” They simply doubted the Premier’s capacity to bring the military into line. That doubt did not end after the war when historians looked at the evidence, which reflected such a shaky balance of power in Tokyo that Konoye’s parley might have precipitated a crisis rather than have averted it. Konoye had neither the nerve nor the muscle for a supreme stroke. Much would have depended on the Emperor, and the administration did not fully appreciate in September either his desire for effective negotiations or his ability to make his soldiers accept their outcome.

The mystery lay not with Hull, who was sticking to his principles, but with Roosevelt, who was bent on

Realpolitik

as well as morality. The President still had one simple approach to Japan—to play for time—while he conducted the cold war with Germany. Why, then, did he not insist on a Pacific conference as an easy way

to gain time? Partly because such a conference might bring a showdown

too

quickly; better, Roosevelt calculated, to let Hull do the thing he was so good at—talk and talk, without letting negotiations either lapse or come to a head. And partly because Roosevelt was succumbing to his own tendency to string things out.

He

had infinite time in the Far East; he did not realize that in Tokyo a different clock was ticking.

Amid the confusion and miscalculation there was one hard, unshakable issue: China. In all their sweeping proposals to pull out of China, the Japanese insisted, except toward the end, on leaving some troops as security, ostensibly at least, against the Chinese Communists. Even the Japanese diplomats’ definite promises on China seemed idle; it was as clear in Washington as in Tokyo that a withdrawal from a war to which Japan had given so much blood and treasure would cause a convulsion.

Washington was in almost as tight a bind on China as was Tokyo. During this period the administration was fearful of a Chinese collapse. Chungking was complaining about the paucity of American aid; some Kuomintang officials charged that Washington was interested only in Europe and hoped to leave China to deal with Japan. Madame Chiang at a dinner party accused Roosevelt and Churchill of ignoring China at their Atlantic meeting and trying to appease Japan; the Generalissimo chided his wife for her impulsive outburst but did not disagree. Every fragment of a report of a Japanese-American détente set off a paroxysm of fear in Chungking. Through all their myriad channels into the administration the Nationalists were maintaining steady pressure against compromise with Tokyo and for an immensely enlarged and hastened aid program to China.

Even the President’s son James, as a Marine captain, urged his father to send bombers to China, in response to a letter from Soong stating that in fourteen months “not a single plane sufficiently supplied with armament and ammunition so that it could actually be used to fire has reached China.” Chiang was literally receiving the run-around in Washington as requests bounced from department to department and from Americans to British and back again. Its very failure to aid China made the administration all the more sensitive to any act that might break Kuomintang morale.

So Roosevelt backed Hull’s militant posture toward Tokyo. When the Secretary penciled a few lines at the end of September to the effect that the Japanese had hardened their position on the basic questions, Roosevelt said he wholly agreed with his conclusion—even though he must have known that Hull was oversimplifying the situation to the point of distortion. Increasingly

anxious, Grew, in Tokyo, felt that he simply was not getting through to the President on the possibilities of a summit conference. On October 2 Hull again stated his principles and demanded specifics. The Konoye government in turn asked Washington just what it wanted Japan to do. Would not the Americans lay their cards on the table? Time was fleeting; the military now were pressing heavily on the diplomats. At this desperate moment the Japanese government offered flatly to “evacuate all its troops from China.” But the military deadline had arrived. Was it too late?

Not often have two powers been in such close communication but with such faulty perceptions of each other. They were exchanging information and views through a dozen channels; they were both conducting effective espionage; there were countless long conversations, Hull having spent at least one hundred hours talking with Nomura. The problem was too much information, not too little—and too much that was irrelevant, confusing, and badly analyzed. The two nations grappled like clumsy giants, each with a dozen myopic eyes that saw too little and too much.

For some time Grew and others had been warning Washington that the Konoye Cabinet would fall unless diplomacy began to score; the administration seemed unmoved. On October 16 Konoye submitted his resignation to the Emperor. In his stead Hirohito appointed Minister of War Hideki Tojo. The news produced dismay in Washington, where Roosevelt canceled a regular Cabinet meeting to talk with his War Cabinet, and a near-panic in

Chungking, which feared that the man of Manchuria would seek first of all to finish off the China incident. But reassurances came from Tokyo: Konoye indicated that the new Cabinet would continue to emphasize diplomacy, and the new Foreign Minister, Shigenori Togo, was a professional diplomat and not a fire-breathing militarist. As for Tojo, power ennobles as well as corrupts. Perhaps it had been a shrewd move of the Emperor, some of the more helpful Washingtonians reflected, to make Tojo responsible for holding his fellow militarists in check.

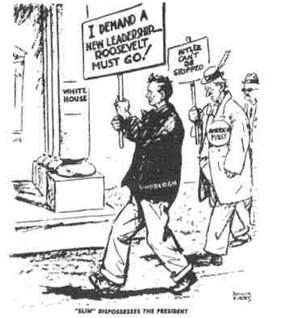

October 13, 1941, Rollin Kirby, reprinted by permission of the New York

Post

October 31,1941, Rollin Kirby, reprinted by permission of the New York

Post

So for a couple of weeks the President marked time. Since he was still following the diplomacy of delay, he could only wait for the new regime in Tokyo to take the initiative—and to wonder when the next clash would occur in the Atlantic.

That clash came on the night of October 16. About four hundred miles south of Iceland a slow convoy of forty ships, escorted by only four corvettes, ran into a pack of U-boats. After three ships were torpedoed and sunk, the convoy appealed to Reykjavik for help, and soon five American destroyers were racing to the scene. That evening the submarines, standing out two or three miles from the convoy and thus beyond the range of the destroyers’ sound gear, picked off seven more ships. The destroyers, which had no radar, thrashed about in confusion in the pitch dark, dropping depth bombs; when the U.S.S.

Kearny

had to stop to allow a corvette to cross her bow, a torpedo struck her, knocked out her power for a time, and killed eleven of her crew. She struggled back to Iceland nursing some bitter lessons in night fighting.

At last the first blood had been drawn—and it was American blood (though the U-boat commander had not known the nationality of the destroyer he was firing at). News of the encounter reached Washington on the eve of a vote in the House on repealing the Neutrality Act’s ban against the arming of merchant ships. Repeal passed by a handsome majority, 259 to 138. The bill had now to go to the Senate. On Navy Day, October 27, the President took up the incident. He reminded his listeners, packed into the grand ballroom of Washington’s Mayflower Hotel, of the

Greer

and

Kearny

episodes.

“We have wished to avoid shooting. But the shooting has started. And history has recorded who fired the first shot. In the long run, however, all that will matter is who fired the last shot.

“America has been attacked. The U.S.S.

Kearny

is not just a Navy ship. She belongs to every man, woman, and child in this Nation….”

The President said he had two documents in his possession: a Nazi map of South America and part of Central America realigning it into five vassal states; and a Nazi plan “to abolish all existing

religions—Catholic, Protestant, Mohammedan, Hindu, Buddhist, and Jewish alike”—if Hitler won. “The God of Blood and Iron will take the place of the God of Love and Mercy.” He denounced apologists for Hitler. “The Nazis have made up their own list of modern American heroes. It is, fortunately, a short list. I am glad that it does not contain my name.” The President had never been more histrionic. He reverted to the clashes on the sea. “I say that we do not propose to take this lying down.” He described steps in Congress to eliminate “hamstringing” provisions of the Neutrality Act. “That is the course of honesty and of realism.

“Our American merchant ships must be armed to defend themselves against the rattlesnakes of the sea.

“Our American merchant ships must be free to carry our American goods into the harbors of our friends.

“Our American merchant ships must be protected by our American Navy.

“In the light of a good many years of personal experience, I think that it can be said that it can never be doubted that the goods will be delivered by this Nation, whose Navy believes in the tradition of ‘Damn the torpedoes; full speed ahead!’ ”

Some had said that Americans had grown fat and flabby and lazy. They had not; again and again they had overcome hard challenges.

“Today in the face of this newest and greatest challenge of them all, we Americans have cleared our decks and taken our battle stations….”

It was one of Roosevelt’s most importunate speeches, but it seemed to have little effect. After a week of furious attacks by Senate isolationists, neutrality revision cleared the upper chamber by only 50 to 37. In mid-November a turbulent House passed the Senate bill by a majority vote of only 212 to 194. The President won less support from Democrats on this vote than he had on Lend-Lease. It was clear to all—and this was the key factor in Roosevelt’s calculations—that if the administration could have such a close shave as this on the primitive question of arming cargo ships, the President could not depend on Congress at this point to vote through a declaration of war. Three days after Roosevelt’s Navy Day speech the American destroyer

Reuben James

was torpedoed, with the loss of 115 of the crew, including all the officers; Congress and the people seemed to greet this heavy loss with fatalistic resignation.

It was inexplicable. In this looming crisis the United States seemed deadlocked—its President handcuffed, its Congress irresolute, its people divided and confused. There were reasons running back deep into American history, reasons embedded in the country’s Constitution, habits, institutions, moods, and attitudes. But

the immediate, proximate reason lay with the President of the United States. He had been following a middle course between the all-out interventionists and those who wanted more time; he had been stranded midway between his promise to keep America out of war and his excoriation of Nazism as a total threat to his nation. He had called Hitlerism inhuman, ruthless, cruel, barbarous, piratical, godless, pagan, brutal, tyrannical, and absolutely bent on world domination. He had even issued the ultimate warning: that if Hitler won in Europe, Americans would be forced into a war on their own soil “as costly and as devastating as that which now rages on the Russian front.”