Roosevelt (94 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

The following night Roosevelt spoke from his car in Soldier Field in Chicago. Nobody there that night would ever forget it, Rosenman said later. Over 100,000 people packed the stadium; another 100,000 or more waited outside. A cold wind was blowing in from the lake; Roosevelt’s words bounced off the far sides of the stadium and back; but somehow he held the crowd.

It was the strangest campaign he had ever seen, the President said. He quoted the Republicans as saying that the “incompetent blunderers and bunglers in Washington” had passed excellent laws for economic progress; that the “quarrelsome, tired old men” had built the greatest military machine the world had ever known—that none of this would be changed—and “Therefore it is time for a change.”

“They also say in effect, ‘Those inefficient and worn-out crackpots have really begun to lay the foundations of a lasting world peace. If you elect us, we will not change any of that, either.’ ‘But,’

they whisper, ‘we’ll do it in such a way that we won’t lose the support even of Gerald Nye or Gerald Smith—and this is very important—we won’t lose the support of any isolationist campaign contributor. Why, we will be able to satisfy even the

Chicago Tribune.’ ”

The President spoke mainly about the economic past and future. He recited the entire economic bill of rights of the previous January. He promised “close to” sixty million productive jobs. He talked about homes, hospitals, highways, parkways, of thousands of new airports, of new cheap automobiles, new health clinics. He proposed that Congress make the FEPC permanent; that foreign trade be trebled after the war; that small business be aided; that the TVA principle be extended to the Missouri, Arkansas, and Columbia River basins. He expressed his belief in free enterprise and the profit system—in “exceptional rewards for innovation, skill, and risk-taking in business.”

For Dewey, too, it was a strange campaign. Like his predecessors Willkie and Landon and especially Hoover, he found it impossible to come to grips with his adversary. He had plenty of hard evidence for his charges of mismanagement and red tape and expediency—but words meant little in the face of MacArthur’s and Eisenhower’s triumphs abroad. He was infuriated by Roosevelt’s bringing up the question of enforcing the peace—a question he had understood to be barred from the campaign in the interest of bipartisan unity. He had occasional strokes of luck, such as Selective Service Director Hershey’s remark that the government could keep people in the Army about as cheaply as it could create an agency for them when they came out. But Roosevelt was quick to have Stimson shush up Hershey and to make clear his own plans for rapid demobilization.

Dewey’s actual position on policy was directly in the presidential Republican tradition—moderate liberalism, moderate internationalism—but the President attacked not the Dewey Republicans but the Taft, Martin, and Fish Republicans. In one speech Roosevelt even turned topsy-turvy one of the oldest and proudest GOP war cries—its stand for stable currency—when he asserted that the “Democratic Party in this war has been the party of sound money,” and the Republican party of unsound. To Dewey, as to Hoover, Roosevelt seemed a political chameleon.

With the polls predicting a close election but with Roosevelt in the lead, Dewey acted more and more like a prosecutor trying to put the President in the dock. And he gravitated more and more toward Communism as the issue. In the final days of the campaign he charged in Boston that to perpetuate himself in office for

sixteen years his opponent had put his party on the auction block, for sale to the highest bidder. The highest bidders were the PAC and the Communist party. Roosevelt had pardoned Earl Browder, he said, in time to organize the fourth-term election. “Now the Communists are seizing control of the New Deal, through which they aim to control the Government of the United States.” By now Democratic leaders were telling Rosenman and Sherwood that the President must answer the charges—the voters feared Communism more than Nazism or fascism.

Roosevelt had long disliked Dewey; now his attitude had become one of “unvarnished contempt.” Bringing his campaign to a climax in Boston three days before the election, he met Dewey’s charges with ridicule.

“Speaking here in Boston, a Republican candidate said—and pardon me if I quote him correctly—that happens to be an old habit of mine—he said that, quote, ‘the Communists are seizing control of the New Deal, through which they aim to control the Government of the United States.’ Unquote.

“However, on that very same day, that very same candidate had spoken in Worcester, and he said that with Republican victory in November, quote, ‘we can end one-man government, and we can forever remove the threat of monarchy in the United States.’

“Now, really—which is it—Communism or monarchy?

“I do not think that we could have both in this country, even if we wanted either, which we do not.

“No, we want neither Communism nor monarchy. We want to live under our Constitution which has served pretty well for a hundred and fifty-five years. And, if this were a banquet hall instead of a ball park, I would propose a toast that we will continue to live under this Constitution for another hundred and fifty-five years.

“Everybody knows that I was reluctant to run for the Presidency again this year. But since this campaign developed, I tell you frankly that I have become most anxious to win—and I say that for the reason that never before in my lifetime has a campaign been filled with such misrepresentation, distortion, and falsehood. Never since 1928 have there been so many attempts to stimulate in America racial or religious intolerance.

“When any politician or any political candidate stands up and says, solemnly, that there is danger that the Government of the United States—your Government—could be sold out to the Communists—then I say that that candidate reveals—and I’ll be polite—a shocking lack of trust in America….”

Al Smith had died early in October, and to the Irish of Boston the President cited the lesson of Al Smith:

“When I talked here in Boston in 1928, I talked about racial and

religious intolerance, which was then—as unfortunately it still is, to some extent—‘a menace to the liberties of America.’

“And all the bigots in those days were gunning for Al Smith….

“Today,” he told the roaring, partisan crowd, “in this war, our fine boys are fighting magnificently all over the world and among those boys are the Murphys and the Kellys, the Smiths and the Joneses, the Cohens, the Carusos, the Kowalskis, the Schultzes, the Olsens, the Swobodas, and—right in with all the rest of them—the Cabots and the Lowells.”

It had been in Boston in 1940 that the President had made his famous pledge to the mothers of America that their sons would not be sent into any foreign war. He would retract nothing now.

“I am sure that any real American—any real, red-blooded American—would have chosen, as this Government did, to fight when our own soil was made the object of a sneak attack. As for myself, under the same circumstances, I would choose to do the same thing—again and again and again….”

On the day before the election, the President talked in the frosty open air to his “neighbors” on both sides of the Hudson. Election eve he gave a radio broadcast to the nation, ending with a prayer composed by Bishop Angus Dun, of Washington. Election Day he voted, along with forty million other Americans; like some of them he had trouble with the voting machine, and a mild oath floated out from behind the curtain.

In the evening the old ritual was followed in the mansion above the Hudson: the dining-room table was cleared, tally sheets and pencils laid out, the big radio and the news tickers turned on. Leahy sat with the President; Eleanor welcomed guests and staff—the Morgenthaus, the Watsons, Sherwood, Rosenman, Early, Hassett, Grace Tully—who clustered in the library. From the start, the President was calm and confident—well poised, unexcited, courteous, and considerate as always, Hassett noted. Once again, after a few ambiguous returns, the big Eastern and urban states began to fall solidly in line for the President. Shortly after eleven the torchlight parade arrived with fife and drum. The President talked quietly from the portico about election nights in the old days, when people would come in farm wagons for a Democratic celebration.

Dewey did not concede until after 3:00

A.M.

Only then did the President go upstairs to bed. In the corridor he turned to Hassett and said: “I still think he is a son of a bitch.”

The ballots were still being counted across the nation. Some Negroes had, “on this little note,” passed their votes to Mr. Franklin D. Roosevelt because they were not allowed into their polls. One vote had been received in the White House in the form of a letter from a black woman in Pittsburgh:

“I have all way believed

That when God put you in the White House

He shore did no that you were the right

Man for the poor people.

I have never got anything

When the other party was in.

Only when you became Prest. did I get

What was do for the poor person.

Dear Mr. Roosevelt

No matter what the other partie say

I am all way for you…

So I am praying to the Good Lord above That he will take good care of you

And put you back in the White House

For as long as you live

For you are the man for us.”

T

HERE WAS A GREAT

flutter in Union Station as the President’s train pulled in three days after the election. Truman, Stimson, Wallace, and other notables climbed aboard to welcome the conquering hero back to the capital. The Police Band sounded “Hail to the Chief” with ruffles and flourishes. It was like New York all over again. Despite the driving rain the President ordered the top put down; Truman and Wallace squeezed in with him, while young Johnnie Boettiger sat grandly in front. Outside, in Union Plaza, 30,000 people waited in the downpour. The car stopped and a panel of microphones was slid across the President’s lap. He would always remember this welcome home, he told the crowd.

“And when I say a welcome home, I hope that some of the scribes in the papers won’t intimate that I expect to make Washington my permanent residence for the rest of my life!”

Behind police motorcycles a long sleek line of limousines paraded up Pennsylvania Avenue. A half-dozen bands played. Over 300,000 people, including federal employees given time off and children let out of school, craned their heads and applauded as the presidential car went by. Soon after reaching the White House the President was greeting the staff, receiving congratulations from officials, and holding a press conference. He had no news, he said, except that he had underestimated his electoral votes. A reporter asked: “Mr. President, may I be the first to ask if you will run in 1948?” The President laughed with the others at the hoary old question.

It was a time of sweet victory. Not only had he beaten Dewey by 432 electoral votes to 99, but he had won the big Northeastern states, half the Midwest, including Illinois and Michigan, and all the West except Wyoming and Colorado. Only the Plains states had gone solidly for Dewey. The President’s strength in Congress had been boosted. Formidable isolationists or conservatives had fallen: Gerald Nye, James J. Davis, of Pennsylvania, Guy Gillette; and leading Senate stalwarts, including Bob Wagner, Claude Pepper, Elbert Thomas, of Utah, Scott Lucas, of Illinois, Lister Hill, of Alabama, and Alben Barkley, had kept their seats. There were some attractive new faces both in the Senate—Brien McMahon, of Connecticut, Fulbright, of Arkansas, Wayne Morse, of Oregon—and in the House—Helen Gahagan Douglas, California New Dealer; Emily Taft Douglas, of Chicago, wife of a University of Chicago economics teacher named Paul Douglas, then serving in the Marines; Adam Clayton Powell, of New York, who claimed to be the first Negro Congressman from the East. Once again Roosevelt had won out against the great majority of the nation’s newspapers; not only the Hearst-Patterson-McCormick-Gannett press, but also Henry Luce’s

Life

and a number of internationalist journals had supported Dewey. And once again he had beaten John L. Lewis in the mine leader’s own precincts in Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

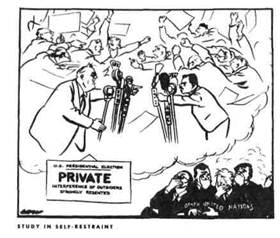

© Low, world copyright reserved, reprinted by permission of the Trustees of Sir David Low’s Estate and Lady Madeline Low

Above all, he had won the referendum of 1944 for American participation in a stronger United Nations. The “great betrayal” of 1920 would not be repeated. He had strengthened his own hand for future negotiations. Congratulations flowed in from abroad—from Churchill, Stalin, Mao Tse-tung.

Physically, the campaign had taken its toll. At times Roosevelt had completely disregarded his rest regimen; he had had to be strenuously active for long periods of time. He seemed more tired than ever after the election; his appetite was poor, his color only fair. But Bruenn found that his blood pressure was actually lower when he was out on the hustings, and when he examined the President two weeks after the election he found that his lungs were clear, the heart sounds were clear and of good quality, there were no diastolic murmurs. Roosevelt’s blood pressure was 210/112.