Roosevelt (26 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

The trip from the airport to the convention was a triumphant procession. His coming out to accept the nomination, Roosevelt told the convention, was a symbol of his intention to avoid hypocrisy and sham. “Let it also be symbolic that in so doing I broke traditions. Let it be from now on the task of our Party to break foolish traditions and leave it to the Republican leadership, far more skilled in that art, to break promises.”

The speech was long and rambling—due in part to a fierce struggle that had been waged over its composition by Roosevelt’s advisers and to Roosevelt’s willingness—while he was bowing and waving to the crowds between airport and convention hall—to placate Howe by substituting the latter’s opening paragraphs for his own. The speech was essentially an appeal for an experimental program of recovery that would steer between radicalism and reaction, that would benefit all the people without falling into an “improvised, hit-or-miss, irresponsible opportunism.” The people that year wanted a real choice, he said. “Ours must be a party of liberal thought, of planned action, of enlightened international outlook, and of the greatest good to the greatest number of our citizens.” Endorsing the party platform “100 per cent,” he lambasted the Republican leaders for their failures and set out in hazy terms a program on taxes, agriculture, tariffs, and recovery.

“I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American People,” Roosevelt wound up in his peroration. The two words

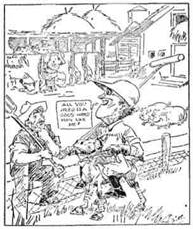

nestling in the speech had meant little to Roosevelt and the other speech writers; soon they were to be more important than the sum of all the other words. Next day a cartoon by Rollin Kirby showed a new “man with a hoe” looking up puzzled but hopeful at an airplane labeled “New Deal.”

How to get the new program off the ground was the mission of Farley, who on Roosevelt’s recommendation was elected the chairman of the Democratic National Committee. The new chairman inherited a superb publicity man in Charles Michelson, ghost writer of scores of speeches that had slashed and pummeled the Hoover administration. Roosevelt’s personal organization was quickly converted into the campaign high command, with headquarters in New York. Soon six hundred people were working through a score of specialized divisions. Considerable attention was devoted to the women’s division, which was headed by a group of imaginative and indefatigable women workers, including Eleanor Roosevelt.

May 26. 1932, Elmer Messner, Rochester

Democrat and Chronicle

HELPFUL FARM HINTS FROM HYDE PARK, Oct. 25, 1932, Ding Darling,

©

1932, New York

Herald Tribune,

Inc.

On one thing Roosevelt and Farley were insistent: they must bypass the cumbersome pyramid of state and county committees and establish a direct personal link with 140,000 local party workers whose names had been collected during the preconvention campaign. Along with millions of buttons and leaflets these

committeemen received personal letters from Roosevelt and Farley, the latter’s signed in green ink. Farley saw the campaign as a party battle and sought to keep control under the top Democratic regulars. “We are going to have every kind of club function we can,” he told a meeting of party leaders early in August, “but we don’t want them running wild.” Farley wanted to prevent crossed wires, but straight party control had its disadvantages too. Special groups did not get full attention; labor especially was handled in a slipshod fashion.

The softest spot in the Roosevelt forces, however, was Tammany. What would the Sachems do? Farley got an answer the day he returned from Chicago, when he had the temerity to invade the Hall during a patriotic ceremony. The gallery hissed; the Sachems on the platform sat in stony silence. But Tammany had little freedom of action; its course depended largely on two men, Smith and Walker.

Crushed and bitter, Smith had left Chicago before Roosevelt arrived. It was nip and tuck for a while whether he would openly attack the victor. He did not—but when Roosevelt emissaries urged him to support the ticket, he balked. “I think he wants to work it out in his own way and in his own time,” Roosevelt wrote Frankfurter. Al did; in the final weeks before the election he campaigned vigorously for Roosevelt in Massachusetts and Connecticut.

Walker presented a different problem. Seabury’s probe of corruption in New York City had come to a head—as it had been deliberately timed to do in order to embarrass him, Roosevelt suspected—in the weeks just before the convention with charges against the mayor. Walker, who had swaggeringly voted against Roosevelt in the convention, shortly afterward filed his answers. During late August, with the election campaign under way, Roosevelt presided over a series of hearings in Albany. The situation required all his political finesse. Some Tammany leaders were in an ugly mood and openly talked of bolting the ticket; even Father Charles Coughlin, the radio priest, wrote from Detroit asking that Walker be given his day in court. The Republicans blew the case into a national issue of Roosevelt and Tammanyism. Day after day the governor in judicial mien patiently questioned the mayor about his tangled affairs. Under mounting pressure, Walker suddenly resigned, accusing Roosevelt of “unfair, unAmerican” conduct of the hearing. The governor had walked the political tightrope expertly. He stripped the Republicans of a national issue without losing Tammany, which was divided on the matter and in any case did not dare to turn against Roosevelt openly.

With the Walker case disposed of, Roosevelt could begin his campaign in earnest. He had received a good deal of advice to the effect that (a) the election was already “in the bag,” and (b) a

campaign tour might jeopardize the Democratic lead. Roosevelt spurned both ideas. He was cautious—almost superstitious—about assuming victory. He believed that a campaign trip would carry the attack to Hoover; moreover, it would demonstrate his physical vigor and silence the whispering against his health. Besides—he simply wanted to go. “My Dutch is up,” he told Farley.

Never, perhaps, has a candidate had as large and varied a group of advisers as Roosevelt collected for his campaign. They ranged from idealistic college professors to cynical party politicians, and they spoke for almost every political viewpoint of right, left, and center. One or two advisers tried to sort out the ideas in logical form for the candidate, but it was a trying task. Roosevelt loved to juggle ideas, he hated to antagonize people, he was looking for proposals that would appeal to a wide variety of groups, whatever the lack of internal consistency. While the candidate toured the streets and talked from the back platform of trains, fierce fights broke out in speech-drafting sessions between high-tariff and low-tariff men, among advocates of various farm policies, between the budget-balancers and public works advocates.

What did the candidate say? At this critical juncture of the nation’s affairs, what program did he offer the American people?

As in past campaigns, Roosevelt devoted each major speech to a major topic. In Topeka he promised to reorganize the Department of Agriculture; he favored the “planned use of land,” lower taxes for farmers through tax reform, federal credit for refinancing farm mortgages, and lower tariffs; and he came out for the barest shadow of a voluntary domestic allotment plan to handle farm surpluses. In Salt Lake City he outlined a comprehensive plan of federal regulation and aid for the floundering railroad industry. In Seattle he let loose a thundering attack on high tariffs. In Portland he demanded full publicity as to the financial activities of public utilities, regulation of holding companies by the Federal Power Commission, regulation of the issuing of stocks and bonds, and use of the prudent-investment principle in rate-making. In Detroit he called for removing the causes of poverty—but he refused to spell out the methods because it was Sunday and he would not talk politics!

One speech in particular excited observers on the left. At the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco Roosevelt talked eloquently about the need for an economic constitutional order, about the role of government as umpire, with federal regulation as a last resort. Although the implications of these ideas for a specific program were left vague, the speech was studded with phrases about economic oligarchy, the shaping of an economic bill of rights, the need for more purchasing power, and every man’s right to life, which

Roosevelt defined as including the right to make a comfortable living. But these ideas seemed to fade away later in the campaign as the candidate turned to other notions, some of them more orthodox than those of Hoover himself.

It was all very confusing to the close observer. He was sure that Roosevelt was against prohibition, reporter Elmer Davis wrote, but for the rest—“You could not quarrel with a single one of his generalities; you seldom can. But what they mean (if anything) is known only to Franklin D. Roosevelt and his God.”

Roosevelt found it easier to assail Hoover’s policies than to spell out clear proposals of his own. The administration, he declared, had encouraged speculation and overproduction through its fake economic policies. It had tried to minimize the gravity of the Depression. It had wrongly blamed other nations for causing the crash. It had “refused to recognize and correct the evils at home which had brought it forth; it delayed relief; it forgot reform.” And Roosevelt and a thousand orators painted President Hoover as sitting in the White House inert, unconcerned, withdrawn.

Hoover launched a vigorous counteroffensive. He concentrated his fire on what he called the radicalism and collectivism in Roosevelt’s proposals. It was perhaps to meet this attack, perhaps for other reasons unknown, that Roosevelt toned down the sweep of his proposals midway in the campaign. He so modified his tariff-reduction stand that his position differed little from that of his adversary in the White House. He hoped that governmental interference to bring about business stabilization could be “kept at a minimum”—perhaps limited simply to publicity. He took a weak stand on unemployment, pledging that no one would starve under the New Deal, that the federal government would set an example on wages and hours, seeking to persuade industry to do likewise, and would set up employment exchanges, leaving unemployment insurance to the states. He promised co-operation with Congress—and with both parties in Congress. And in one of the most sweeping statements of his campaign he berated Hoover for spending and deficits, and he promised—with only the tiniest of escape clauses—to balance the budget.

Here was no call to action, no summons to a crusade. Roosevelt had no

program

to offer, only a collection of proposals, some well thought out, like the railroad plan, others vague to the point of meaninglessness. On the whole he was remarkably temperate; there was little passion or pugnacity. Some of his speeches, indeed, had the flavor of academic lectures, as Roosevelt led his audience through the Hoover policies and then described his own. For a nation caught in economic crisis, it was a curious campaign.

What was Roosevelt up to? He was trying to win an election, not lay out a coherent philosophy of government. He had no such philosophy; but he knew how to pick up votes, how to capture group support, how to change pace and policy. “Weave the two together,” he said to an astonished Raymond Moley when the academic man presented Roosevelt with two utterly different drafts on tariff policy. “I think that you will agree,” he wrote to Floyd Olson about his Topeka farm speech, “that it is sufficiently far to the left to prevent any further suggestion that I am leaning to the right.”

“A chameleon on plaid,” Hoover growled. With his orderly engineer’s mind he could not come to grips with this antagonist who fenced all around him, now on the left, now on the right, now in attack, and now in sudden retreat. Nor could Norman Thomas, the Socialist candidate for President, with his elaborate, eloquent, detailed platform. It was not 1896, or 1912, or even 1928. In the gravest economic crisis of their history the American people, still benumbed and bewildered, seemed only to stir lethargically amid the tempests of the politicians.

On election eve Roosevelt gave a last talk to his neighbors in Poughkeepsie. He spoke of the “vivid flashes” of the campaign—the great crowd under the lights before the capitol in Jefferson City, the Kansans listening patiently under the hot sun in Topeka, the “strong, direct kindness” of the people in Wyoming who had come hundreds of miles to see him, the sunset in McCook, Nebraska, the children in wheel chairs at Warm Springs, the stirring trip north through New England.