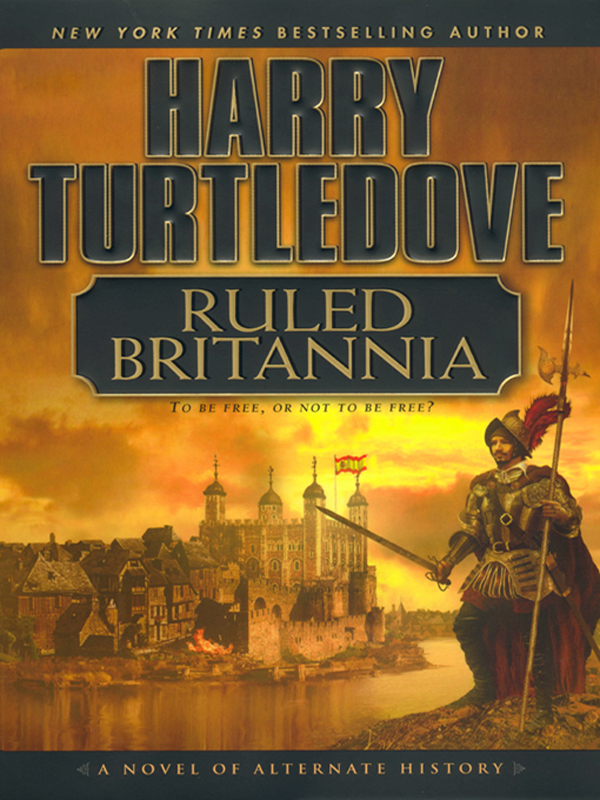

Ruled Britannia

Authors: Harry Turtledove

Â

Â

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Â

Ruled Britannia

Â

A New American Library Book / published by arrangement with the author

Â

All rights reserved.

Copyright ©2002 by Harry Turtledove

This book may not be reproduced in whole or part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

Â

The Penguin Putnam Inc. World Wide Web site address is

http://www.penguinputnam.com

Â

ISBN: 978-1-1012-1251-6

Â

A NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY BOOK®

New American Library Books first published by The New American Library Publishing Group, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

New American Library and the “ ” design are trademarks belonging to Penguin Putnam Inc.

” design are trademarks belonging to Penguin Putnam Inc.

Â

Electronic edition: July, 2003

Â

T

WO

S

PANISH SOLDIERS

swaggered up Tower Street toward William Shakespeare. Their boots squelched in the mud. One wore a rusty corselet with his high-crowned morion, the other a similar helmet with a jacket of quilted cotton. Rapiers swung at their hips. The fellow with the corselet carried a pike longer than he was tall; the other shouldered an arquebus. Their lean, swarthy faces wore what looked like permanent sneers.

People scrambled out of their way: apprentices without ruffs and in plain wool caps; a pipe-smoking sailor wearing white trousers with spiral stripes of blue; a merchant's wife in a red wool doublet spotted with whiteâalmost a man's styleâwho lifted her long black skirt to keep it out of puddles; a ragged farmer in from the countryside with a donkey weighted down with sacks of beans.

Shakespeare flattened himself against the rough, weather-faded timbers of a shop along with everybody else. The Spaniards had held Londonâheld it down for Queen Isabella, daughter of Philip of Spain, and her husband, Albert of Austriaâfor more than nine years now. Everyone knew what happened to men rash enough to show them disrespect to their faces.

A cold, nasty autumn drizzle began sifting down from the gray sky. Shakespeare tugged his hat down lower on his forehead to keep the rain out of his eyesâand to keep the world from seeing how thin his hair was getting in front, though he was only thirty-three. He scratched at the little chin beard he wore. Where was the justice in that?

On went the Spaniards. One of them kicked at a skinny, ginger-colored dog gnawing a dead rat. The dog skittered away. The soldier almost measured himself full length in the sloppy street. His friend grabbed his arm to steady him.

Behind them, the Englishmen and -women got back to their business. A pockmarked tavern tout took Shakespeare's hand. “Try the Red Bear, friend,” the fellow said, breathing beer fumes and the stink of rotting teeth into his face. “The drink is good, the wenches friendlyâ”

“Away with you.” Shakespeare twisted free. The man's dirty hand, he noted with annoyance, had smudged the sleeve of his lime-green doublet.

“Away with me? Away with me?” the tout squeaked. “Am I a black-beetle, for you to squash?”

“Black-beetle or no, I'll spurn you with my foot if you trouble me more,” Shakespeare said. He was a tall man, on the lean side but solidly made and well fed. The tout's skin stretched drumhead tight over cheekbones and jaw. He slunk off to earn his penniesâhis farthings, more likelyâsomewhere else.

A few doors down stood the tailor's shop to which Shakespeare had been going. The man working inside peered at him through spectacles that magnified his red-tracked eyes. “Good morrow to you, Master Will,” he said. “By God, I am glad to see you in health.”

“And I you, Master Jenkins,” Shakespeare replied. “Your good wife is well, I hope, and your son?”

“Very well, the both of them,” the tailor said. “I thank you for asking. Peter would be here to greet you as well, but he is taking to the head of the fishmongers a cloak I but now finished: to their hall in Thames Street, in Bridge Ward.”

“May the fishmongers' chief have joy in it,” Shakespeare said. “And have you also finished the kingly robe you promised for the players?”

Behind those thick lenses, Jenkins' eyes grew bigger and wider yet. “Was that to be done today?”

Shakespeare clapped a hand to his forehead, almost knocking off his hat. As he grabbed for it, he said, “Â 'Sblood, Master Jenkins, how many

times did I tell you it was wanted on All Saints' Day, and is that not today?”

“It is. It is. And I can only cry your pardon,” Jenkins said mournfully.

“That doth me no good, nor my fellow players,” Shakespeare said. “Shall Burbage swagger forth in his shirt tomorrow? He'll kill me when he hears this, and I you afterwards.” He shook his head at thatâfury outrunning sense.

To the tailor, fury counted for more. “It's near done,” he said. “If you'll but bide, I

can

finish it within an hour, or may my head answer for it.” He made a placating gesture and, even more to the point, shoved aside the doublet on which he'd been sewing.

“An hour?” Shakespeare sighed heavily, while Jenkins gave an eager nod. Drumming his fingers on his arm, Shakespeare nodded, too. “Let it be as you say, then. Were it not that the royal robe in our tiring room looks more like a vagabond's rags and tatters, I'd show you less patience.”

“Truly, Master Will, you are a great gentleman,” Jenkins quavered as he took the robe of scarlet velvet from under the counter.

“I trust you'll note this unseemly delay in your price,” Shakespeare said. By the tailor's expression, he found that not in the least gentlemanly. While Shakespeare kept on drumming his fingers, Jenkins sewed in the last gaudy bits of golden thread and hemmed the robe.

“You could wear it in the street, Master Will, and have the commonality bow and scrape before you as if in sooth you were a great lord,” he said, chuckling.

“I could wear it in the street and be seized and flung in the Counter for dressing above my station,” Shakespeare retorted. “Â 'Tis a thing forbidden actors, save when on the stage.” Jenkins only chuckled again; he knew that perfectly well.

He was finished almost as soon as he'd promised, and held up the robe to Shakespeare as if he were the tireman about to dress him in it. “You did but jest as to the scot, I am sure,” he said.

“Â 'Steeth, Master Jenkins, I did not. Is mine own time a worthless thing, that I should spend it freely for the sake of your broken promise?”

“Broken it was not, for I promised the robe today, and here it is.”

“And had I come at eventide, and not of the morning? You had been forsworn then. You may have mended your promise, but that means not it was unbroken.”

They argued a while longer, more or less good-naturedly. At last, the tailor took five shillings off the price he'd set before. “More than you

deserve, but for the sake of your future custom I shall do't,” he told Shakespeare. “Which still leaves you owing fourteen pounds, five shillings, sixpence.”

“The stuffs you use are dear indeed,” Shakespeare grumbled as he gave Jenkins the money. Some of the silver and copper coins he set on the counter bore the images of Isabella and Albert, othersâthe older, more worn, onesâthat of the deposed Elizabeth, who still languished in the Tower of London, only a furlong or so from where Shakespeare stood. He looked outside. It was still drizzling. “Can you give me somewhat wherewith to cover this robe, Master Jenkins? I am not fain to have the weeping heavens smirch it.”

“I believe I may. Let me see.” Jenkins rummaged under the counter and came up with a piece of coarse canvas that had seen better days. “Here, will this serve?” At Shakespeare's brusque nod, the tailor wrapped the cloth around the robe and tied it with some twine. He bobbed his head to Shakespeare as he passed him the bundle. “Here you are, Master Will, and I am sorry for the inconvenience I put you to.”

Shakespeare sighed. “No help for it. Now I needs mustâ” Horns blared and drums thudded out in the street. He jumped. “What's that?”

“Did you not recall?” The tailor's face twisted. “By decree of the Spaniards, 'tis the day of the great auto de fe.”

“Oh, a pox! You are right, and it had gone out of my head altogether.” Shakespeare looked out into the street as horn calls and drums came again. In response to that music, people swarmed from all directions to gape at the spectacle.

“A lucky man, who can forget the inquisitors,” Jenkins said. “A month gone by, as is their custom, they came down Tower Street making proclamation that this . . . ceremony would be held.” He might have been about to offer some comment on the auto de fe, but he didn't. Shakespeare couldn't blame him for watching his tongue. In London these days, a word that reached the wrong ears could mean disaster for a man.

He felt disaster of a different, smaller, sort brushing against him. “In this swarm of mankind, I shall be an age making my way back to my lodgings.”

“Why not go with the parade to Tower Hill and see what's to be seen?” Jenkins said. “After all, when in Rome . . . and we are all Romans now, is't not so?” He chuckled once more.

So did Shakespeare, sourly. “How could it be otherwise?” he

returned. In Elizabeth's day, Catholic recusants had had to pay a fine for refusing to attend Protestant services. Now, with their Catholic Majesties ruling England, with the Inquisition and the Jesuits zealously bringing the country back under the dominion of the Pope, not going to Mass could and often did mean worse than fines. Like most people, Shakespeare conformed, as he'd conformed under Elizabeth. Some folk went to church simply because it was the safe thing to do; some, after nine years and more of Catholic rule, because they'd come to believe. But almost everyone did go.

“Why not what?” Jenkins repeated. “Think what you will of the dons and the monks, but they do make a brave show. Mayhap you'll spy some bit of business you can filch for one of your dramas.”

Shakespeare had thought nothing could make him want to watch an auto de fe. Now he discovered he was wrong. He nodded to the tailor. “I thank you, Master Jenkins. I had not thought of that. Perhaps I shall.” He tucked the robe under his arm, settled his hat more firmly on his head, and went out into Tower Street.

Spanish soldiersâand some blond-bearded Englishmen loyal to Isabella and Albertâin helmets and corselets held pikes horizontally in front of their bodies to keep back the crowd and let the procession move toward Tower Hill. They looked as if they would use those spears, and the swords hanging from their belts, at the slightest excuse. Perhaps because of that, no one gave them any such excuse.

Two or three rows of people stood in front of Shakespeare, but he had no trouble seeing over any of them save one woman whose steeple-crowned hat came up to the level of his eyes. He looked east, toward the church of St. Margaret in Pattens' Lane, from which the procession was coming. At its head strode the trumpeters and drummers, who blasted out another fanfare even as he turned to look at them.

More grim-faced soldiers marched at their heels: again, Spaniards and Englishmen mixed. Some bore pikes. Others carried arquebuses or longer, heavier muskets. Tiny wisps of smoke rose from the lengths of slow match the men with firearms bore to discharge their pieces. The drizzle had almost stopped while Shakespeare waited for the tailor to finish the robe. In wetter weather, the matchlocks would have been useless as anything but clubs. As they marched, they talked with one another in an argot that had grown up since the Armada's men came ashore, with Spanish lisps and trills mingling with the slow sonorities of English.

Behind the soldiers tramped a hundred woodmongers in the gaudy livery of their company.

One of those robes would do as well to play the king in as that which I have here

, Shakespeare thought. But the woodmongers, whose goods would feed the fires that burned heretics today, seemed to be playing soldiers themselves: like the armored men ahead of them, they too marched with arquebuses and pikes.

From a second-story window across the street from Shakespeare, a woman shouted, “Shame on you, Jack Scrope!” One of the woodmongers carrying a pike whipped his head around to see who had cried out, but no faces showed at that window. A dull flush stained the fellow's cheeks as he strode on.

Next came a party of black-robed Dominican friarsâmostly Spaniards, by their looksâbefore whom a white cross was carried. They chanted psalms in Latin as they paraded up Tower Street.

After them marched Charles Neville, the Earl of Westmorland, the Protector of the English Inquisition. The northerner's face was hard and closed and proud. He had risen against Elizabeth a generation before, spent years in exile in the Netherlands, and surely relished every chance he got for revenge against the Protestants. The old man carried the standard of the Inquisition, and held it high.

For a moment, Shakespeare's gaze swung to the left, to the gray bulk of the Tower, though the church of Allhallows Barking hid part of the fortress from view. He wondered if, from one of those towers, Elizabeth were watching the auto de fe. What would the imprisoned Queen be thinking if she were? Did she thank King Philip for sparing her life after the Duke of Parma's professional soldiers swept aside her English levies? “Though she herself slew a queen, I shall not stoop to do likewise,” Philip had said. Was that generosity? Or did Elizabeth, with all she'd labored so long to build torn to pieces around her, reckon her confinement more like hell on earth?