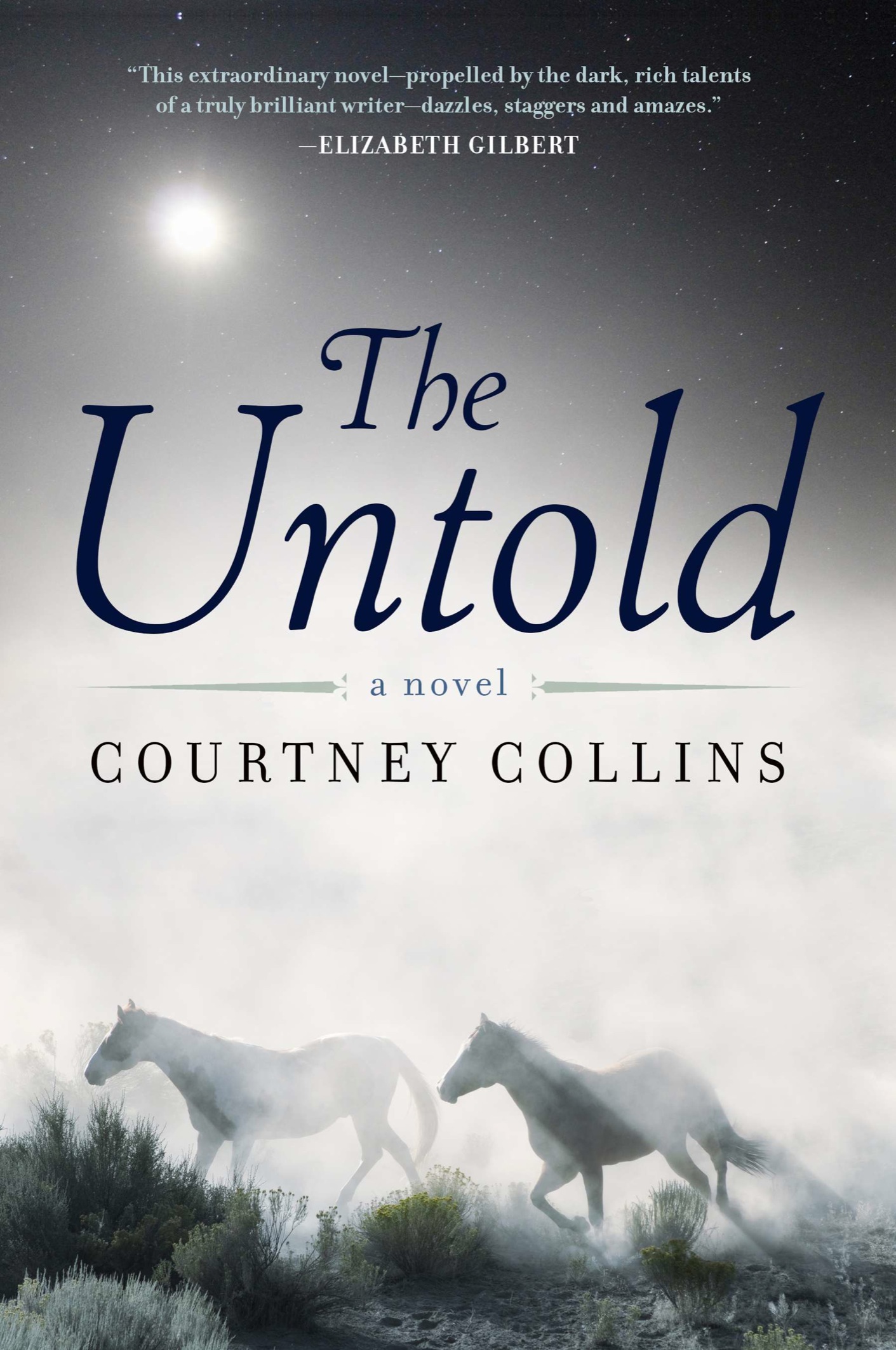

The Untold

Authors: Courtney Collins

AMY EINHORN BOOKS

Published by G. P. Putnam's Sons

Publishers Since 1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA ⢠Canada ⢠UK ⢠Ireland ⢠Australia ⢠New Zealand ⢠India ⢠South Africa ⢠China

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2012 by Courtney Collins

First edition: Allen & Unwin 2012

First American edition: Amy Einhorn Books 2014

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

“Amy Einhorn Books” and the “ae” logo are registered trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) LLC

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Random House Group Limited for permission to reprint lines from “Tonight I Can Write,” from

Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair

by Pablo Neruda, published by Vintage Books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Collins, Courtney.

[The Burial]

The untold / Courtney Collins.âFirst American Edition.

p. cm.

Previously published by: Sydney : Allen & Unwin 2012, as The Burial.

ISBN 978-0-698-13867-4

1. Hickman, Elizabeth Jessie, b. 1890âFiction. 2. AustraliaâHistoryâ 20th centuryâFiction. 3. Biographical fiction. I. Title.

PS3603.O4527B87 2014 2013036915

813'.6âdc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For my mother, with

love

Â

Â

The truth of the heavens is the stars unyoked from their constellations and traversing it like escaped horses.

â

JEAN GIRAUDOUX

,

Sodom and Gomorrah

This is all. In the distance someone is singing. In the distance. My soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.

â

PABLO N

ERUDA

, “Tonight I Can Write”

How could we ever keep love a-burning day after day if it wasn't that we, and they, surrounded it with magic tricks . . .

â

HARRY

HOUDINI

This is a work of fictionâinspired by art, music, literature and the landscape, as much as by the life and times

of Jessie Hickman

herself.

W

HO HASN'T HEARD

of Harry Houdini? The Big Bamboozler. The Great Escapologist. The Loneliest Man in the World.

I

T IS 1910.

Harry Houdini, the World's Wonder, the Only and Original, is up to his armpits in mud. Intractable fingers of sea grass and kelp surge around him. With his eyes open, he can see movement and murky shadows.

He knows that above him twenty thousand peopleâstevedores, clerks, women in hatsâanticipate his death. They line Queens Bridge three deep. Past Flinders Street Station, all the way to Princes Bridge, they crane their necks and jostle for a view. Some have fallen over, tripped on hems and the clerk's pointed shoe, to see him, the World's Wonder, dive into the Yarra, handcuffed and wrapped in chains.

Slapped by sea grass, shrinking from shadows, Houdini brings his wrists to his mouth. With his teeth he pulls out a pin, one from each handcuff. The cuffs fall free and sink farther down.

Houdini grabs at the weeds around him to anchor himself.

They are loose and rootless, like slack rope. It is as if the river has no baseâjust layers and layers of sediment floating upon one another.

He tucks up his short legs and digs his knees into the sludge. His knee scrapes against some rock or reef and he reaches down to follow its seam. He runs his hand over a moss-covered thing, smooth becoming fibrous, until his fingers catch in the familiar loops of a chain. The chain is thick and he follows its links until his hands hit up against a leg iron. And though he is running out of breath and he has yet to free himself from the locks around his neck, his hands seize around the thing within the leg iron. It breaks off. An ankle? A foot? Certainly not rock.

The thing is a thing of limbs.

Houdini gags. He takes in water. The taste is rotten. The thing of limbs is so eaten away by fish that Houdini's grasp has freed it. He is still clutching part of its brittle remains when the larger part of the body floats up and over him. It is the bluntest of shadows.

Houdini beats into the sediment with his legs, stirring up a cloud of silt and other undiscovered things. He swims upwards at an angle, away from the cloud, away from the body, and reaches into his swimsuit for a key. He is just below the surface, veiled by murky water, when he finally frees himself from the locks around his neck. He breaks the surface and raises the locks above his head. Twenty thousand people cheer.

His wet curls conceal his face from the crowd as he turns in the water, searching for the body, the bloated mass. The river reveals nothing but ripples moving unevenly out to sea.

Houdini treads water, waiting for a boat. His chest aches. The rowers move too slowly, their oars striking and slicing the water in

a rhythm that does not match the urgency he feels. He coughs and spits as they grow nearer. Finally, one of the rowers reaches down to him while the other balances the boat.

You swallow the river, Mr. Houdini?

Houdini does not answer. He grips the man's arm and hauls himself up and into the boat.

Houdini is silent as the two men row him back to shore. His eyes continue to search the surface of the water but there is no sign of the bloated body and he cannot think of how to explain it or who to

tell.

I

f the dirt could speak, whose story would it tell? Would it favor the ones who have knelt upon it, whose fingers have split turning it over with their hands? Those who, in the evening, would collapse weeping and bleeding into it as if the dirt were their mother? Or would it favor those who seek to be far, far from it, like birds screeching tearless through the sky?

This must be the longing of the dirt, for the ones who are suspended in flight.

Down here I have come to know two things: birds fall down and dirt can wait. Eventually, teeth and skin and twists of bone will all be given up to it. And one day those who seek to be high up and far from it will find themselves planted like a gnarly root in its dark, tight soil. Just as I have.

This must be the lesson of the dirt.

M

ORNING

OF MY BIRTH.

My mother was digging. Soot-covered and bloody. If you could not see her, you would have surely smelt her in this dark. I was trussed to her in a torn-up sheet. Rain and wind scoured us from both sides, but she went on digging. Her heart was in my ear. I pushed my face into the fan of her ribs and tasted her. She tasted of rust and death.

In the wind, in the squall, I became an encumbrance. She set me on the ground beside her horse. Cold on my back and wet, I

could see my breath breathe out. Beside me, her horse was sinking into the mud. I watched him with one eye as he tried to recover his hooves. I knew if he trod on me he would surely flatten my head like a plate.

Morning of my birth, there were no stars in the sky. My mother went on digging. A pile of dirt rose around her until it was just her arms, her shoulders, her hair, sweeping in and out of the dark while her horse coughed and whined above me.

When she finally arched herself out of the hole in the ground she looked like the wrecked figurehead on a ship's bow. Hopeful as I was, I thought we might take off again, although I knew there was no boat or raft to carry us, only Houdini, her spooked horse. And from where we had come, there was no returning.

She stood above me, her hair willowy strips, the rain as heavy as stones. Finally, she stooped to pick me up and I felt her hand beneath my back. She brought me to her chest, kissed my muddied head. Again, I pushed my face into the bony hollow of her chest and breathed my mother in.

M

ORNING

OF MY BIRTH,

my mother buried me in a hole that was two feet deep. Strong though she was, she was weak from my birth, and as she dug, the wind filled the hole with leaves and the rain collapsed it with mud so all that was left was a wet and spindly bed.

When the sun inched awkwardly up she lowered me into the grave. Then, lying prone on the earth, she stroked my head and sang to me. I had never, in my short life, heard her sing. She sang

to me until the song got caught in her throat. Even as she bawled and spluttered, her open hand covered my body like the warmest blanket.

I had an instinct then to take her song and sing it back to her, and I opened my mouth wide to make a sound, but instead of air there was only fluid and as I gasped I felt my lungs fold in. In that first light of morning my body contorted and I saw my own fingers reaching up to her, desperate things.

She held them and I felt them still and I felt them collapse. And then she said,

Sh, sh, my darling.

And then she slit my throat.

I

SH

OULD NOT HAVE SEEN

the sky turn pink or the day seep in. I should not have seen my mother's pale arms sweep out and heap wet earth upon me or the screeching white birds fan out over her head.

But I did.