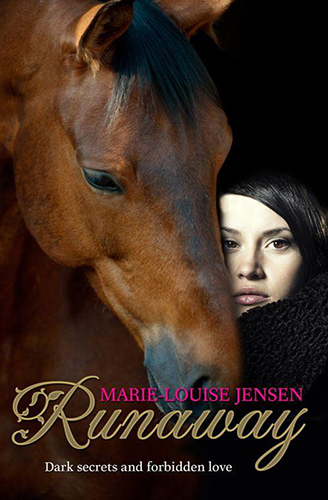

Runaway

Authors: Marie-Louise Jensen

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Historical, #Love & Romance

For Helle, Gregory, and Paul;

the centre of my world.

‘We’ll be safe here, Charlie,’ my father said as he shut the thin door of the new lodgings behind us. He put down our heavy trunk on the worn, creaking boards and rubbed his hands together to get the circulation going again.

I looked around the room with a sick rush of disappointment. We’d moved so many times in the last few weeks, giving a different name to each new landlord. Each time we moved, it was worse. Each room was shabbier and more run-down than the last. This one had been whitewashed once, but the grubby walls bore the traces of many previous occupants and there was a pile of refuse in one corner. The meagre furnishings were battered and dirty. The stairwell stank of cabbage, latrines, and poverty. Many desperate families were crowded into similar cramped rooms in the building. I could smell hopelessness mingling with the other odours. I could never have believed we’d end up somewhere like this.

I was increasingly concerned for my father’s well-being. First my mother had died of that dreadful sickness. Then we’d left the Americas to return to England, where I knew not a soul. My brother, to my great distress, had chosen to stay the other side of the ocean. And now my father worsened day by day … But it wouldn’t do to say so. ‘That’s good, father,’ I said instead. ‘I hope this move will give you some peace of mind.’

He embraced me and kissed me on each cheek by way of reply. ‘You’re such a good girl, Charlotte,’ he said warmly. ‘Your mother would be proud of you, God rest her soul. I’m so sorry to put you through this. Perhaps we made a mistake leaving America. You think we did, don’t you?’

I sighed. ‘I miss our friends,’ I agreed. ‘And I know we didn’t live in luxury there, but this … ’ I looked around the sordid lodging with distaste.

‘I know, I know.’ My father passed one hand over his face, rubbing his greying stubble. His once upright figure had become a little stooped of late and his former military neatness was sadly compromised.

‘But this is temporary. I felt certain I was bettering us by returning to England. I had good reason for believing that, Charlotte. I still do! One day soon, you will see.’

My father began exploring the room, hunting for a loose floorboard. He found one beside the battered closet and concealed his papers there. Once he’d had valuables to hide too, but if there was anything left, I didn’t know about it.

A sparkle came into father’s eyes as he straightened up; a faint reminder of his former, cheerful self. I felt a surge of affection for him. Such a dear, loving father he’d always been to my brother and me.

‘Here you are, my dear,’ he said, delving two fingers into his coat and pressing a coin into my hand. ‘Take this and go and find us a hot pie while I unpack. We must celebrate our new abode in style!’

I smiled back. Our pleasures were few nowadays and my father’s joys were rare. I was more than willing to celebrate, however modestly. Standing on tiptoe, I kissed his thin cheek. ‘Why don’t you lie down and rest instead of unpacking?’ I suggested.

‘I

am

a little tired,’ he admitted with a small sigh.

I hunted in my luggage for a brush and ran it through my long brown hair, which had been tangled by the wind earlier. My gown was patched and shabby, but I shook out my petticoats so they fell more neatly. I picked up the coin again and blew father a kiss. Closing the door carefully behind me, I ran down the creaking stairs.

The street was dusty and full of refuse. The stench was appalling. There could be no greater contrast between the poor quarters of London, teeming with ragged humanity and filth, and the places I had grown up, the open spaces of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, where my father had served in a private company of the English Army. The land there was sparsely settled and the air crisp and clean. Here the air was rank with foul vapours.

My search for a pie shop led me to busier streets where horses, wagons, street sellers, and pedestrians thronged the thoroughfares. The rumble of wheels on cobbles, the clatter of hooves, the tramp of boots, and loud voices created a bewildering hubbub. I was anxious about becoming lost; London was a vast maze to me.

The sharp crack of a whip cut through the general noise. Startled, I turned. An elderly, rather gaunt bay horse was straining between the shafts of a cart. The muscles were standing out on his neck as he threw his weight into the collar. A searing memory tore through me as I saw the horse. I’d been grieved to leave my own beloved bay mare behind in America. This horse was quite different, but the colouring reminded me of her nonetheless. The lash fell viciously again, this time drawing blood from the horse’s shoulder. He snorted in pain and fright and redoubled his efforts, straining obediently until his eyes bulged, but the cart didn’t move an inch.

‘Get up, you lazy creature!’ shouted the driver, raising his arm once more.

‘Stop! Stop!’ I cried, rushing forward. ‘Try looking, before you lash your horse! Your wheel is jammed!’ I ran out into the road and placed myself in front of the maltreated beast, putting a hand on his bridle. The man could not drive his horse forward over me, so lowered his whip arm and began shouting at me.

‘The wheel of your cart is jammed between two stones,’ I shouted over his obscenities. ‘You need to back up, not try to force your poor beast forward!’

Several other passers-by had also stopped. A buxom woman with a basket had spotted the jammed wheel too and was crying shame on the driver. ‘Don’t beat the poor, defenceless beast for somethin’ that’s none o’ his fault!’ she shouted.

By the time three or four people had joined the fray, the driver finally stopped swearing long enough to take a look. As he climbed down to examine the wheel, I soothed his horse by stroking his dark, whiskery nose and speaking calmly to him. The horse rolled his eyes at first, quivering with fear and pain. Gradually, however, responding to my voice and gentle touch, he quietened.

I helped back the horse, while two men pushed at the cart to free it from the rut between the cobbles. ‘Make sure you check your wheels next time, before you strike your horse!’ scolded the woman with the basket once the cart was free again. I gave the horse a final pat, bid him a reluctant farewell and stood aside. I felt an ache in my heart as he trotted away. I’d spent my life with horses. The worst thing about being suddenly so poor was being deprived of their companionable, comforting presence.

Realizing I’d been gone much longer than planned and my father would be fretting about my safety, I asked the woman with the basket if she could direct me to a pie shop. There I bought a steak and kidney pie wrapped in paper and hurried back towards the lodging before it could cool.

I knew there was something wrong as soon as I saw the door was ajar. I’d closed it behind me, leaving my father resting; I knew that for certain. I climbed the last stairs silently, approaching the doorway with caution. I could hear a rustling and things falling to the floor. The hairs on the back of my neck rose. My father would never throw things around in that way. Was someone robbing us?

Softly, I laid the wrapped pie down on the dusty wooden floorboards and put my hand on the doorframe, trying to peer in. Perhaps I hadn’t noticed a floorboard creak beneath my feet. Perhaps I cast a shadow through the doorway. Whatever it was, I gave myself away.

The door was yanked open; I was seized roughly and dragged into the room. I yelled once but before I could do more I was slammed against the wall, face first, and held there. My head spun sickeningly from the impact. A smooth voice spoke in my ear: ‘There’s a knife against your throat. No noise!’

Cold metal pressed against my warm skin. Terror flooded me, turning my limbs to water. In the mere second I’d had to glimpse the room, I’d taken in a scene of chaos; I’d seen blood.

‘Where’s my father?’ I asked in a shaking voice. ‘What do you want?’

‘I want to know where your father’s papers are,’ the man’s voice whispered, his breath hot on my cheek. I flinched away, but stopped short when the sharp tip of the knife pricked my throat. My breathing was coming in short gasps and there were black spots dancing before my eyes.

‘I … don’t … know,’ I stammered.

‘Tell me!’ The man pulled me back and slammed me against the wall again. Stars exploded behind my eyes and nausea rushed over me. ‘He doesn’t … tell me. Why don’t … you ask him?’

The man grasped my hair and twisted me brutally around, staying behind me, so that I could see the room.

The table and both chairs were overturned. The closet, the only other furnishing in the small room, was on its side, the door torn off. Our trunk had been emptied and smashed; its contents strewn across the room. The mattresses had been slashed open, their straw filling scattered. I saw all this in a few horrified seconds. And then I saw my father and there was no longer room for anything else in my mind.

Father lay sprawled across the piles of clothing in the far corner of the room. My first thought was that he looked broken; his body lay at a strange angle. Then I saw the deep cuts on his face and throat. Blood had soaked into his clothing and run onto the floor, staining it bright red.

I was used to the sight of injury and death. I was a soldier’s daughter, after all. But this wasn’t battle, nor was it the body of a stranger. This was my father.

I fought to get to him, but I was held impossibly tight. My head burned from the blows it had received and from the tight grip on my hair.

‘Please,’ I begged. ‘Please let me go to him. He’s hurt.’

My captor shook me. ‘Nothing’s hurting him any more,’ he whispered. ‘And if you don’t want to end in the same state, tell me where his papers … ’

There was a sharp rap at the door and we both froze. I considered crying out, but the knife was pressed harder against my throat. The man released my hair only to clamp his hand over my mouth, pulling me back against him.

‘I’ve come for the rent,’ said a high-pitched voice outside the room. It was the landlady.

‘Don’t think you can escape me,’ the man hissed in my ear. ‘I know who you are, Charlotte, and I’ll find you like I found your father. No matter where you go or how well you try to hide. I’ll get what I want sooner or later. Tell me now! It’s the only way you’ll ever be free of me.’

He lifted his hand slightly from my mouth, keeping it hovering there, ready to clamp back down if I tried to call out. At the same time he pushed the knife deeper. I felt it sting as it drew blood.

I kept stubbornly silent, my breathing ragged with pain and fear. The landlady was on the other side of the door, listening hard no doubt. All she had to do was open it, and I had a chance. She was nosy enough to do so, I knew.

Please

, I begged her silently.

Just push the door open!

The handle turned and the door creaked open. My captor exploded into action. I was flung aside and crashed heavily into the overturned closet, striking my hip and shoulder so hard that I almost fainted from the pain. The man pulled the landlady into the room. No doubt he would have threatened her as he’d threatened me, but he was foiled. Outside the door stood her son and the two children from the room across the hall, all watching curiously. He couldn’t kill all of us.

With a furious oath, he shouldered his way violently past them and thundered away down the stairs. I’d caught only a brief glimpse of his face, but I noted he looked like a gentleman, not the sort of ruffian you’d expect to find robbing paupers.

I picked myself up off the floor and staggered over to my father. The attacker was right. He was beyond my aid. His eyes stared, glassy and unseeing, at the cracked ceiling. His still-warm hand, when I clasped it, was limp. There was blood everywhere.

Behind me, the landlady approached, took in the sight of all the blood and my father lying lifeless, and let out a piercing scream. I jumped and looked up. Hands clasped to her mouth she stared at the spectacle.

‘Dead?’ she whispered at last.

I nodded. ‘His throat’s been cut,’ I said. I couldn’t recognize my own voice.